Leaders have little faith in religious protection bill to tackle hate

Labor’s new religious discrimination bill will fail unless it allows freedom of speech but also protects against vilification, the nation’s religious leaders warn.

Labor’s new religious discrimination bill will fail unless it allows freedom of speech but also protects against vilification, the nation’s religious leaders warn as tensions over the Israel-Hamas war grow in Australia.

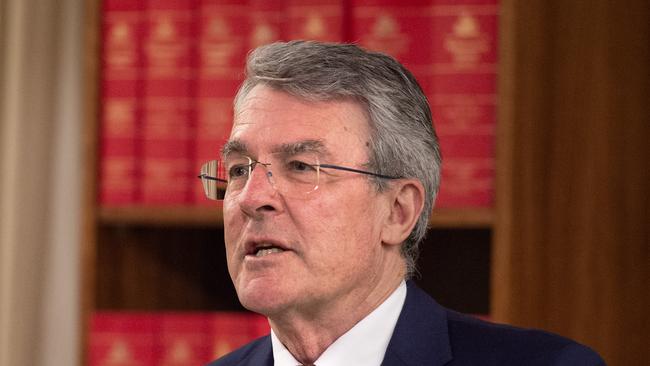

After receiving a long-awaited framework for a new religious freedoms regime that was due on New Year’s Eve, Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus has told faith leaders he is working on a draft bill that will be ready before July.

But Jewish and Muslim leaders want to see how any bill will shield their constituents from hate speech before giving it their backing, with one senior Jewish figure saying vilification could stall the process by adding “another layer of complexity and controversy to the debate”.

Concerns about protections against hate speech have mounted in the weeks since the October 7 attack by terrorist group Hamas against Israel, which saw Australia gripped by a wave of anti-Semitic incidents including a protest where chants of “gas the Jews” were heard at the steps of the Sydney Opera House.

The warning comes as Labor battles to regain ground among religious voters, with the latest Newspoll showing the Coalition as the preferred party of Christian voters. Fifty-five per cent say they support the opposition, while Labor is the preferred party of 64 per cent of non-religious voters.

Australia/Israel & Jewish Affairs Council executive director Colin Rubenstein said it was important that any religious discrimination bill was “workable and enforceable” to ensure society remains “free from religious and racial discrimination and incitement to violence”. “It is important that any legislation strikes the right balance between freedom of speech, including the right to promote religious beliefs, and the need to prevent hate speech that can do so much to damage the fabric of our multicultural society,” he said.

“Sadly, there have been recent examples of such hate speech from religious figures, against Jews and other minorities.

“There is profound apprehension and anxiety in the Australian Jewish community, especially in light of the recent huge spike in anti-Semitism here and around the world.”

Religious discrimination proved to be a stumbling block for the Morrison government in its final year.

The Coalition’s attempts to legislate protections promised to religious communities after the 2017 same-sex marriage vote were stalled over the treatment of gay and transgender people by religious schools. Labor pledged to introduce its own discrimination bill at the last election.

Clerics and education leaders anticipate Mr Dreyfus’s draft will include amendments to prevent religious vilification and discriminatory statements, and protect LGBTI students.

The Coalition’s bill introduced to parliament in early 2022 would have protected most statements of religious belief – such as teachings on same-sex marriage – from other discrimination laws.

But the Coalition bill said that statements that could be reasonably considered to be “malicious” or could “threaten, intimidate, harass or vilify a person or group” would not have had protection.

Therefore, anti-Semitic statements by preachers and the crowds of the Sydney Opera House protests would not have been shielded and instead would have been dealt with by other state criminal vilification laws.

Labor moved several amendments to the Coalition’s bill, which included changes to the Sex Discrimination Act that would have stopped religious schools expelling gay and transgender students.

Chair of the Sydney Diocese Religious Freedom Reference Group, Bishop Michael Stead, said Labor should reintroduce the Coalition’s bill with its proposed amendments.

“In February 2022, the then Labor opposition supported the Coalition’s version of the Religious Discrimination Bill, subject to three amendments. That bill was drafted as the result of extensive consultation with stakeholders over two years,” he said.

“Given that no substantive consultation with faith communities has yet taken place, I would hope that the government would use the good work that has already gone into the former bill as the basis for its bill, subject to the three amendments that it has already signalled.”

But Executive Council of Australian Jewry co-chief executive Peter Wertheim warned that the government’s intention to introduce a vilification provision could stall the process towards passing a bill, remarking that only “time will tell”.

Such a provision would make it illegal to ridicule someone for their faith, potentially creating a political minefield due to concerns about the infringement of such provisions on free speech that could become a back door blasphemy law.

“I think the government’s announced intention of including a new prohibition against religious vilification has the potential to introduce yet another layer of complexity and controversy to the debate.,” he said.

“Balancing competing rights and freedoms is never straightforward. Reasonable minds will continue to differ on where to strike the balance in certain situations.”

Australian National Imams Council spokesman Bilal Rauf said existing legal protections did not protect Australians on the basis of faith and the Israel conflict had highlighted the need for religious protections was “more pressing than ever”.

“Recently there has been an exponential increase in Islamophobia and anti-Muslim sentiment,” Mr Rauf said. “With the catastrophic conflict in the Middle East, many have experienced increased Islamophobia and anti-Muslim sentiment.

“There is no place for such conduct in modern-day Australia. We need laws to address such conduct and make it clear that discrimination based on a person’s religious belief or activity is unacceptable.”

Following a series of protests which were hijacked by anti-Semitic chants and revelations in The Australian of radical sermons delivered by Sydney Muslim clerics calling for jihad and reciting parables about killing Jews, the NSW government has strengthened its laws criminalising threats or incitements of violence on grounds including race or religion.

Federal opposition legal affairs spokeswoman Michaelia Cash signalled she would be wary of using a civil discrimination bill to tackle vilification.

“The freedom to worship should never be a licence to urge violence. There will always be a need for balance, but civil laws about discrimination should not excuse criminal behaviour,” she said.

“There are longstanding criminal offences in Australia that deal specifically with calls for violence against people on the basis of their religion. That type of conduct should be investigated by police, and dealt with under the criminal law.”

Mr Dreyfus remained tight lipped about any details regarding what the bill would contain, saying that “the Albanese government believes all Australians, including people of faith, have the right to live their lives free of discrimination and we will seek to enhance protections in anti-discrimination law in a way that brings Australians together”.

Australian Federation of Islamic Councils chief executive Kamalle Dabboussy said it was important the issue didn’t become a “political football”, adding that the community needed clarity on religious discrimination laws. Melbourne Catholic Archbishop Peter Comensoli said the church remained optimistic the legislation would ensure faith-based organisations such as schools maintained the freedom to preference the employment of staff who supported the organisation’s religious ethos.

Christian Schools Australia director of public policy Mark Spencer said an ALRC consultation paper released last January had lacked balance and failed to address one aspect of terms of reference that religious schools should be able to continue to build a community of faith.

“We hope that the final recommendations rectify these failings,” Mr Spencer said.

The ALRC released a consultation paper early last year but the framework was panned by religious leaders who argued the model would bar school principals from preferencing teachers with the same beliefs.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout