Reserve Bank will not sit by and let ‘persistent’ supply-side inflation become entrenched: Philip Lowe

Philip Lowe has called for ambitious policies to raise the economy’s speed limit, warning inaction will suppress living standards and entrench high inflation.

Reserve Bank governor Philip Lowe has urged the federal government to implement ambitious policies to raise the economy’s speed limit, warning inaction would suppress living standards and entrench high inflation.

In a speech on Wednesday, Dr Lowe said audacious pay rises not linked to productivity, such as those sought by public sector unions, risked a wage-price spiral that would lead to more punishing interest rates and job losses.

A day after the RBA paused its breakneck monetary tightening, keeping the cash rate at 3.6 per cent, the central bank chief also said mortgage payments were expected to reach a record 10 per cent of household disposable income by the end of next year, as 10 rate hikes take a toll on home prices and consumer spending.

In any case, he said it was premature to talk about rate cuts, as some economists are forecasting for this year, with the RBA more likely than not to raise its cash rate again.

Dr Lowe told the National Press Club in Sydney that productivity growth had stalled over the three years to December, compared with average annual growth in labour productivity of 1.25 per cent in the previous three decades.

He said faster productivity growth delivered “a bigger pie, higher real wages, a lift in our collective wealth and a more prosperous economy”.

“It also means that, for a time, there is less upward pressure on inflation,” he said. “The fact that the supply side of our economy is growing more slowly than it once did carries the implication that demand also needs to grow more slowly if we are to avoid persistently higher inflation.

“Given the importance of lifting productivity growth, it was pleasing to see the Productivity Commission’s most recent five-year report. The good news in that report is that there are plenty of ideas on how we can lift our performance. The task now is to implement some of those ideas.”

In its 1000-page blueprint, published last month, the commission put forward 71 measures, including proposals on skilled migration, labour market flexibility, and lower-cost decarbonisation through expansion of the safeguard mechanism.

Before releasing the report, Jim Chalmers said some of the proposals conflicted with Labor priorities and values.

The Treasurer nominated as too extreme its warning on multi-employer bargaining and a call to abolish green-energy subsidies, but said the government was making progress on many of the issues where it had direct responsibility, including skills and workforce participation.

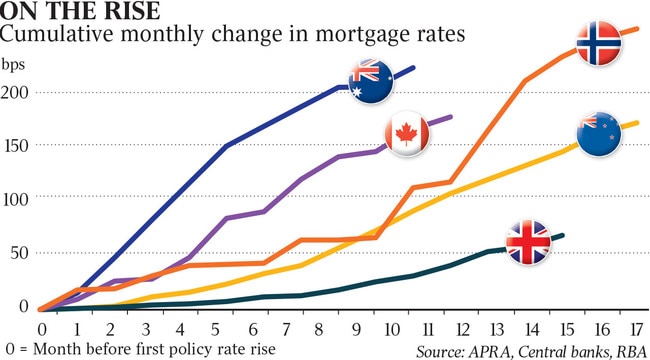

While other central banks continue to raise their more elevated policy rates, Dr Lowe said he was confident the decision to pause was right because of more moderate wages growth here, the RBA’s determination to lock-in a 50-year low in unemployment, and the rapid pace of pass-through by lenders after rate rises,

He said the 35 per cent of households with a mortgage were experiencing, or would experience, a “significant increase in their required payments”.

“The predominance of variable-rate mortgages in Australia means that this is a more powerful transmission mechanism of monetary policy than in many other countries,” he said.

“Since interest rates started rising, the average mortgage rate that Australians pay has increased more quickly than average mortgage rates paid in other countries.

“This increase in mortgage rates has had a significant effect on household budgets and we anticipate that required mortgage payments will reach a new record high of almost 10 per cent of household disposable income by the end of next year.”

During the question and answer session, Dr Lowe said it was “way too early” to talk about cutting interest rates, with the RBA board more likely to raise the cash rate than lower it.

“At the moment, we think we may well have to increase interest rates again, but we’re not 100 per cent certain of that,” he said.

“I think it’s way too early to be talking about interest rate cuts and the balance of risk lies to further rate rises.”

Dr Lowe was asked about a 20 per cent pay claim by the public sector union and said unsustainably high wages growth would cause more pain for the entire community.

“It’s really important that we don’t develop a pattern here where wages and prices chase one another,” he said.

“If they do, then inflation will get entrenched and we’ll have to have higher interest rates.”

The ACTU is pushing for a 7 per cent increase for 2.6 million workers, with the government arguing in its annual wage review submission that hundreds of thousands of low-paid workers should receive inflation-linked pay rises.

Employer groups said granting the peak union body’s “economically reckless” claim for a $57-a-week increase would add $12.6bn a year to employer costs.

The Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry is calling on the Fair Work Commission to limit the pay rise to 3.5 per cent.

There has been persistent criticism that households were bearing the brunt of aggressive monetary policy tightening when the inflationary outbreak has been driven by factors outside the RBA’s control, such as the pandemic disruptions to global supply chains, and then the global energy price shock unleashed by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine early last year.

Dr Lowe said there was no immediate relief in sight for households struggling with sharply climbing rents, as a surprise jump in migration would only be matched with a “modest” housing supply response in coming years.

He expects supply issues will also drive power bills up a further 15 per cent this year, after they jumped 12 per cent in 2022.

Dr Lowe said “standard” monetary policy practice was to look through price shocks caused by supply issues.

“(But) the situation is more complicated when the supply-side issues are persistent, leading to persistently higher price increases in parts of the economy,” he said.

“Here there is a greater risk that inflation expectations and price- and wage-setting behaviour adjusts. If this were to occur, a more decisive monetary policy response would be required.

“It is important to point out, though, that while supply-side factors are influencing how fast inflation declines, they cannot be a reason to tolerate higher inflation on an ongoing basis.”

More Coverage

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout