Rate hikes suggest 15pc house price slump: RBA

The rapid series of rate hikes point to a dramatic fall in house prices, RBA head of domestic markets Jonathan Kearns says.

This year’s rapid-fire rate hikes suggest a house price slump of at least 15 per cent after inflation, with owners of the most expensive properties set to suffer an even bigger hit to their wealth, a senior Reserve Bank official says.

RBA head of domestic markets Jonathan Kearns said the estimate was based on modelling undertaken by the bank earlier this year on the impact from a 2 percentage point increase in interest rates – versus the 2.25 percentage point in hikes already delivered since May.

A “real” drop of 15 per cent would suggest about a 10 per cent nominal fall in prices, once the current inflation rate of 6.1 per cent was taken into account.

House prices nationally are 3.5 per cent down from their pandemic peaks – by 4.2 per cent in the capital cities, and 2.2 per cent in the regions, according to CoreLogic.

Sydney has been the hardest hit market, where values are 7.4 per cent lower, followed by the 4.6 per cent retreat in Melbourne.

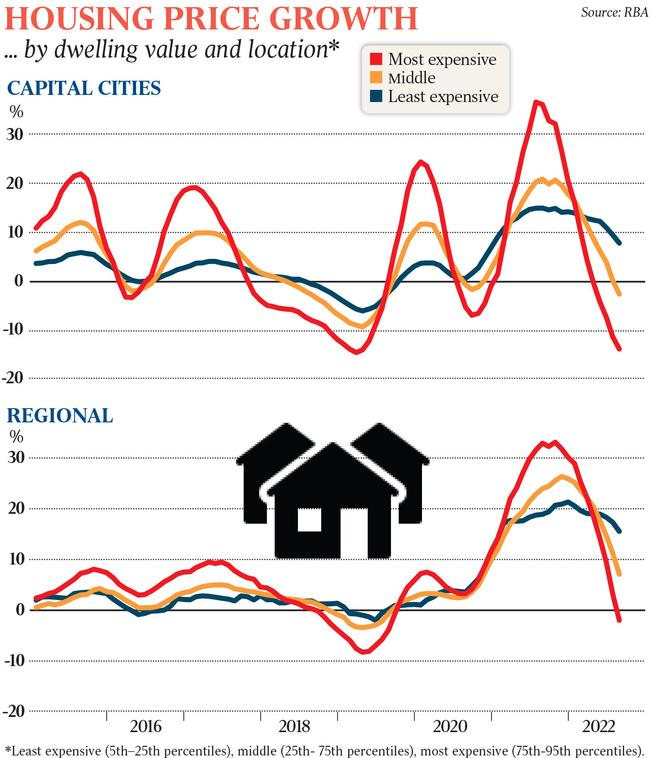

Dr Kearns said RBA research had found “housing prices in the most expensive areas are the most sensitive to interest rate changes”.

“Interest rates can have larger effects on housing prices in locations where the supply of housing is less flexible, mortgage debt is higher, there are more investors and incomes are higher,” he said.

Dr Kearns said that if there was a structural adjustment and rates stayed 2 percentage points higher “forever”, then the implied real fall in average prices would stretch to 30 per cent.

“The impact of interest rates on housing prices importantly depends not only on how much they change, but for how long,” he said.

The RBA board could deliver another blow to mortgage holders when it next meets, with some economists predicting another half a percentage point hike, to 2.85 per cent.

ANZ head of Australian economics David Plank was one of those predicting a fifth straight double rate rise, and said rates would end the year at 3.35 per cent before flatlining through 2023.

Mr Plank said he expected property values would fall as much as 20 per cent from their recent peaks, essentially undoing the pandemic boom.

Higher interest rates would hit household budgets, with Dr Kearns estimating that the average mortgage holder would be paying 25 per cent more on their repayments as a result of the Reserve Bank’s aggressive rate hike cycle this year.

Dr Kearns said higher rates were also restricting the maximum loan size available to new buyers by a fifth, although only one in 10 new homebuyers borrowed at close to their limits.

“And because the assessment rate also applies to any existing debt, the decrease in borrowing capacity is even larger for prospective borrowers who have existing debt, such as property investors,” he said.

Not all borrowers face higher repayments immediately, with 35 per cent of existing mortgage holders on fixed rates, he said, against the historical rate of 20 per cent, as record low rates during the pandemic sparked a massive take-up of fixed-term debt.

“A large share of variable rate borrowers have been making excess mortgage payments into offset and redraw accounts,” Dr Kearns said.

“For many borrowers, these larger payments will mean that actual payments need not increase by the full amount of the change in required payments that result from the higher interest rate,” he said.

Speaking at a property summit in Sydney on Monday morning, Dr Kearns said the estimates of the impact on house prices from higher rates “was not actually a prediction of how much housing prices would change”, and assumed all other things were equal.

“Many factors other than interest rates also influence housing prices. For example, the demand for housing would be greater with stronger household income growth, increased population through immigration, or a preference for fewer people living in each household.

“Conversely, the supply of housing would be lower than expected if construction turns out to be constrained in some way.

“These factors would all lead to stronger demand, or weaker supply, for housing and so housing prices (and rents) would not fall as much as implied by interest rates acting in isolation.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout