Who gives a dam? Ask towns going dry

A slowdown in construction of dams over decades has led to a crisis that might’ve been avoided.

It’s the worst drought in generations, with major towns such as Dubbo in NSW and Stanthorpe in Queensland facing the prospect of running out of water in weeks.

But the story goes back much further: a progressive slowdown in construction of dams over the decades has led to a crisis that might have been avoided had governments met promises to keep on building them.

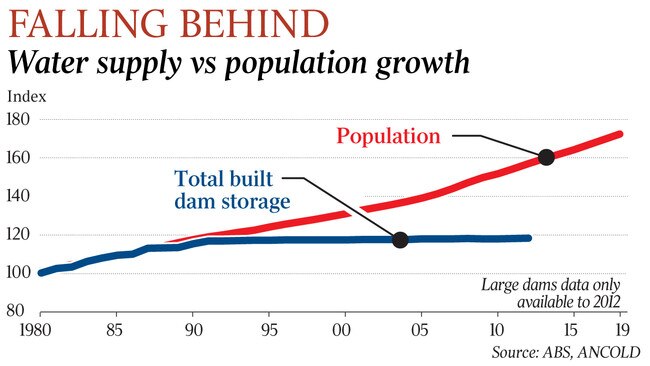

Figures obtained by The Australian from the Australian National Committee on Large Dams, an independent association, show that major dam building substantially slowed at the end of the 1970s and stalled around 1990. There has been less than a 3 per cent increase in large dam storage capacity since then. By contrast, the Australian population has risen by almost half, from 17 million to more than 25 million, sharply reducing the amount of water available to meet demands for household needs, and to provide for agriculture.

Municipal water in Stanthorpe, in Queensland’s southeast, is set to run out by Christmas. For those outside town reliant on rain tanks that are dry, locals are helping charities provide water for purposes as basic as children brushing their teeth.

Farmers are facing extreme stress, and express anger that a long-proposed irrigation project, Emu Swamp Dam, has only just got the go-ahead from the state government after 25 years of debate. Ballandean Estate Wines, run by the Puglisi family, is for the first time planning on trucking in water at huge expense.

“We wouldn’t recoup our costs, but we have to keep vines alive,” said Mario Gangemi, the enterprise’s production manager.

After three years of drought, Accommodation Creek, from which the vineyard usually draws water for irrigation, stopped flowing two years ago. Farm dams have dried up.

Mr Gangemi is married to Leeanne Puglisi-Gangemi. Along with her sister Robyn Puglisi-Henderson, they are the fourth generation to operate the vineyard. Ballandean is one of the farming enterprises to put up a collective $23m in funds towards Emu Swamp Dam. Since 2003, only 20 dams have been completed: two in NSW, one each in Queensland and the ACT, and 16 in Tasmania.

Mr Gangemi said conditions were so extreme that Leeanne and Robyn’s father Angelo Puglisi, a Rotarian, was helping provide water to families who had none.

“They are trucking down pallets of water,” Mr Puglisi said. “They have families who are in need, selecting it from our winery, just to have water to brush their teeth, to have water in schools — that’s how dire it is.”

More than $1bn sits in a federal fund to build dams, but state governments show little impetus to use it to get bulldozers going.

“It is simply not feasible to build a new dam in Victoria,” said a government spokeswoman.

Federal Water Resources Minister David Littleproud yesterday toured the drought and bushfire-ravaged Stanthorpe region in his electorate of Maranoa. He warned the nation’s water woes were set to worsen unless the government’s program of major water infrastructure was set in motion.

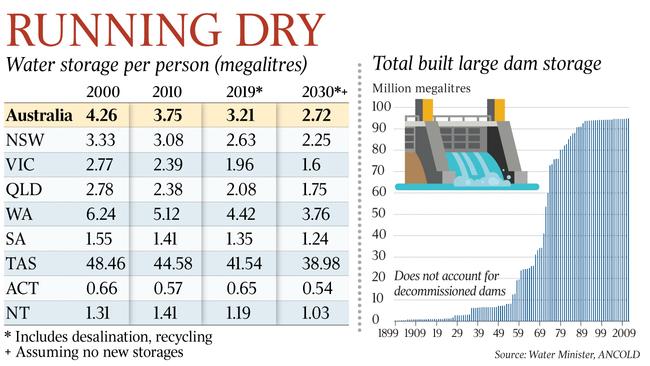

Mr Littleproud released a federal government analysis that found that at current rates, water storage per person in NSW, Victoria and Queensland would fall by more than 30 per cent by 2030 as population grew.

He said the failure by state governments to build dams had placed water storage at risk of falling behind population growth.

In NSW, water storage is expected to decline from 3.3 megalitres per person in 2000 to 2.3ML per person by 2030. Victorians would see a fall from 2.8ML to 1.6ML per person over that period; Queenslanders a decline from 2.8ML to 1.8ML; South Australians a drop from 1.6ML to 1.2ML, and Western Australians a fall from 6.2ML to 3.8ML. Tasmanians would enjoy water storages per person more than 10 times that of the mainland states, but still decline, from 48ML per person to 39ML.

Mr Littleproud said that, although the federal government had offered $1.3bn for new projects through the National Water Infrastructure Development Fund in 2015, it “still had to drag most states kicking and screaming to build new dams”.

“They’re just not keeping up with their growing populations,” he said.

Under the Constitution the states have primary responsibility for water and building dams, but state leaders have often accused federal governments of dragging the chain on funding and federal environmental approvals.

In late 2014, then agriculture minister Barnaby Joyce pushed his ambitious water infrastructure agenda, formally unveiling 27 projects earmarked for commonwealth funding.

“We need to strategically plan our future water infrastructure,” Mr Joyce said at the time.

As revealed by The Australian last month, an analysis of the Coalition’s list of top projects shows it will not have seen a single major dam built or likely even started construction when it next faces voters after nine years in office.

Labor agriculture spokesman Joel Fitzgibbon said: “For six years the government now led by Scott Morrison has been promising dams here, dams there, dams everywhere. Now it seems they’ve given up on dams and have nothing left to offer but to blame the states. The last federal government to build a dam was a Labor government.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout