What Libs did wrong, and how they can make it right

Interviewing key players about the Coalition’s tumultuous nine years in power from 2013 to 2022, I started with a version of: how would they assess the period? The answers were very different.

If you have seen the promos for the resultant Sky News Liberals in Power documentary series, you will know that former defence minister Christopher Pyne’s answer begins, realistically, with one word: “Messy.”

Current deputy Liberal leader Sussan Ley reduced me to incredulous laughter when she began her response: “Stability.”

Her Comical Ali answer did not make it into our final cut but served to demonstrate the difference in realism between serving politicians and those who have rejoined the outside world.

Truth is there were some consistent threads that ran through the three terms and three prime ministers of the Coalition years. Scott Morrison summarised these under the heading of “sovereignty” – encompassing border security, beginning budget repair, protecting the nation during the pandemic, standing up to China, and initiating AUKUS. But the overarching takeout and the overwhelming failure of the period was the lack of stability.

The Coalition was elected in large part to put an end to the chaos of the Rudd-Gillard-Rudd era. And it failed on that central commitment.

This was where the Liberals most blatantly broke faith with voters – the imperatives of policy implementation and stable government were abandoned in favour of personalities and ambition. Like Labor, the Liberals have changed their internal rules to reduce the chances of future prime ministers being torn down, but across almost a decade in power, great opportunities for the party and the country were squandered.

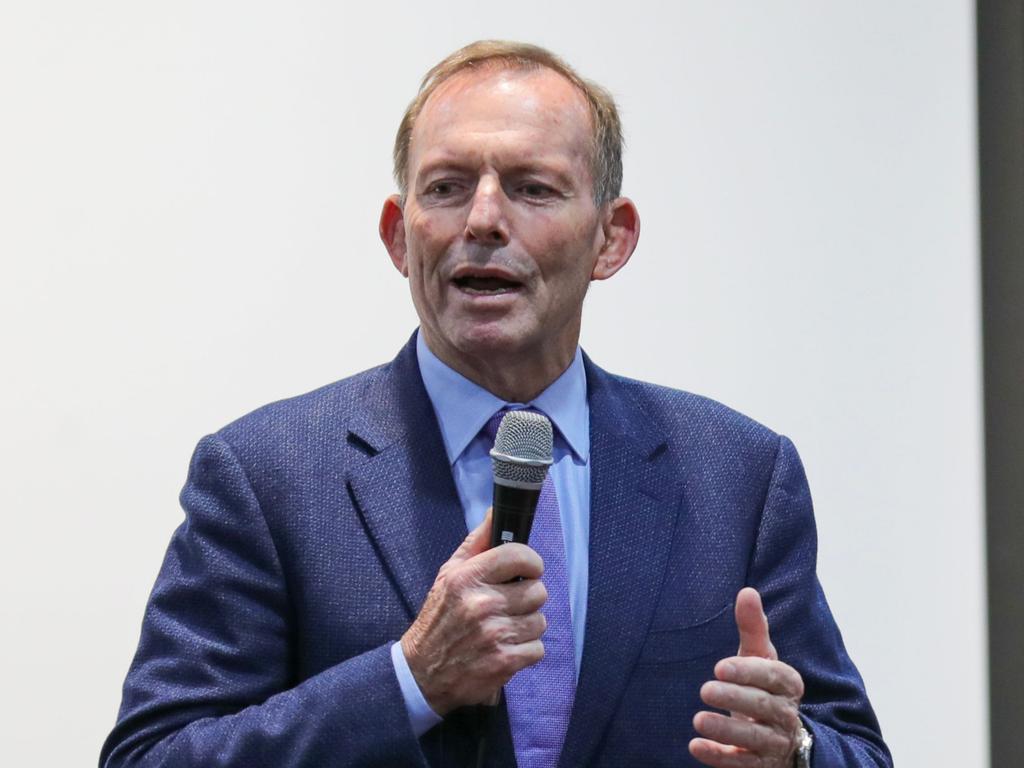

Tony Abbott made many mistakes – most first-term prime ministers do – but perhaps his biggest mistake was to think his colleagues had learned from Labor’s implosion and would treat him as a protected species.

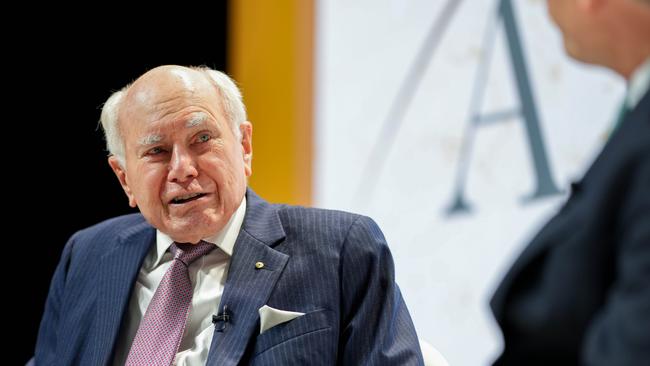

John Howard stressed that the most important relationship any prime minister had was not with voters, media, public servants or industry leaders but with the partyroom colleagues who held his/her leadership in the palms of their hands.

Still, by the time Morrison lost government last year, many other factors had intervened. There was the vicious weaponisation of gender politics driven by the #MeToo zeitgeist; persistent turmoil over climate and energy policy; and the manifestation of these two issues in the rise of the teals.

We are left with a range of questions about the Liberal Party’s organisational resilience, policy positioning and personnel performance as it surveys an Australian mainland without a Coalition government. Before it conquers the path back to power, the party must first map it out.

My time around politics has given me some unique insights and experience around leadership shenanigans and policy contortions. As a reporter, I covered resignations and leadership contests in state politics and was in Parliament House in Canberra the day Paul Keating launched his first challenge against Bob Hawke. I had a senior role with South Australian Liberal premier John Olsen when he was forced to resign and later, as chief-of-staff to Alexander Downer, I was involved in organising the secret cabinet meeting in Sydney during the 2007 Asia-Pacific Economic Co-operation summit that dared to consider a view on Howard’s leadership.

Ultimately, I was chief-of-staff to opposition leader Malcolm Turnbull in 2009 when he was challenged and defeated by Abbott in a climate-driven conflagration decided by a solitary vote.

Leadership changes are truly brutal. For all the benefits and privileges of politics, these times demonstrate why it is a seriously tough vocation.

The more you delve, the more you understand the organic nature of leadership challenges. People like to talk about them being clinical – and, in the end, there is a razor-like focus on raw numbers – but as those numbers swing, defect and coagulate around challengers, the process is fluid, personal and unpredictable.

When Keating revealed the Kirribilli agreement (via Laurie Oakes) in 1991, the story and its implications rushed through the corridors like a tsunami. I swear you could see this information and its potential consequences move like a Mexican wave.

The nauseating ruthlessness of these events was brought back to me when interviewing Pyne, who was a factional player par excellence. An out and proud Moderate Liberal, Pyne was certainly indispensable to Turnbull but was also a leading lieutenant for Abbott.

Given his hyper-political sensibilities and frankness, I expected him to be phlegmatic about the slings and arrows. But even as far back as 2015, when Turnbull challenged Abbott, Pyne was troubled by it all.

“So do you know what I did?” he asked me, rhetorically. “I did my job but I locked the door of my internal office. I thought I’d been through enough of these and I’m sick of them, and it’s going to be bad, and I don’t really get any joy out of what’s going on.”

Now, sure, he must have opened his door at some stage and made sure he was in sweet with the new regime – Pyne is a politician, after all – but he did seem genuinely perturbed by the repeated descent into leadership ructions. He made the rather obvious but important point that governments could not be stable unless contenders could subsume their personal ambitions for the greater good, which obviously did not happen with Turnbull.

Experienced politicians often joke that every MP on Capital Hill believes they can be prime minister, and this is not far from the truth. So just as “losers’ consent” is fundamental to the operation of a peaceful democracy, political parties must rely on some personal patience or voluntary suppression of ambition.

Trent Zimmerman is a former NSW Liberal Party president and was federal member for North Sydney until he was unseated by teal independent Kylea Tink. “One of the major propositions of a political party,” Zimmerman said, “is that in a parliamentary system of government, it offers stability.”

Accordingly, if there was one factor that derailed the Coalition’s period in government, it must be Turnbull’s lust for power. Sure, Abbott took him down six years earlier, but that was driven by policy, and it was in opposition. Sure, Abbott made many terrible errors (appointing only one woman to cabinet, breaking promises, bringing in knighthoods and giving one to Prince Philip), but he was prime minister and the judgment of voters was some time away.

These two titans, whose electorates faced off across the heads of Sydney Harbour, were also the titular heads of the Moderate and Conservative factions. Their history of jousting plays deeply into the foundational and creative tension between the party’s conservative and liberal strains.

“Well, I think the party is too factionalised, but both sides can be blamed,” Howard told me.

Pyne said: “If the Liberal Party thinks it can win from the right it’s going to be in opposition for a long time.”

This ideological positioning is important, but perhaps more pertinent is the organisational distortion of the factions, as outlined by Howard.

“But factions, in my experience in the Liberal Party, really have become preferment co-operatives,” he said, relaying how some branches sign only members sympathetic to their ideological bent. Howard warns against a policy drift to the left to chase teal voters. “Well, you don’t win anything back by embracing the other person’s policy,” he said.

Former education minister Alan Tudge has a similar perspective. “We’ve got to make sure that we fight and fight on issues which aren’t Labor-lite issues but issues which are strong Liberal issues,” he said.

The Liberals’ so-called women problem was weaponised against the Morrison government, but the government made itself vulnerable from the outset with Abbott’s “sex appeal” campaign comment about Fiona Scott and his compulsory inclusion of deputy leader Julie Bishop as the only woman in a 19-person cabinet.

Scott said the six teal members, all women, amounted to a lesson for the Liberals. “And my question to the Liberal Party is really simple,” the former western Sydney MP said. “Why did these women not join the Liberal Party? If they did, why did they leave?”

While Pyne, Scott and Zimmerman believe the party needs to shapeshift, to some degree, towards the teals, Tudge, Howard and others believe the secret to revival hides in plain sight – traditional Liberal values.

Morrison strips the choice back to the bone: “We (Liberals) believe Australians can be amazing and we just want to help them achieve that. And when they’re amazing, the country’s amazing. The Labor Party believes the government can be amazing. I think I’ll go with the people.”

Interviewing numerous key players about the Coalition’s tumultuous nine years in power from 2013 to 2022, I started every discussion with a version of the easy, scene-setting query: how would they assess the period?