Malcolm Turnbull’s final act: ‘Call the G-G’

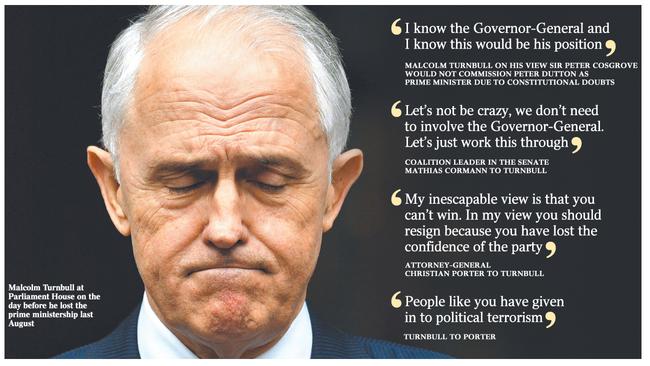

The day before Turnbull was deposed, he clashed with Porter over a last-ditch plan to save his job.

The day before Malcolm Turnbull was deposed, the prime minister clashed with Attorney-General Christian Porter over a last-ditch plan to save his leadership by persuading Governor-General Peter Cosgrove not to commission Peter Dutton as prime minister.

Mr Turnbull’s determination to involve the Governor-General in the leadership crisis last August provoked a showdown between Mr Turnbull and Mr Porter, with the Attorney-General telling the prime minister his stance was “wrong in law” and would involve giving misleading advice to the Governor-General.

The clash occurred in Mr Turnbull’s office on Thursday, August 23. The Attorney-General carried a prepared resignation letter in his pocket, aware that such a difference on a fundamental issue related to Mr Turnbull’s survival could see a request for his resignation.

Mr Porter warned Mr Turnbull that if the prime minister went public at a media conference putting the view that Sir Peter would not be able to commission Mr Dutton as prime minister then Mr Porter, as Attorney-General, would feel obliged to publicly repudiate Mr Turnbull’s position.

“If you go out and say that publicly, then I will feel obliged to reject that position at law,” Mr Porter told Mr Turnbull, in defiance of the prime minister. Any such event would have been disastrous for Mr Turnbull’s effort to save himself.

Mr Porter also told Mr Turnbull that if he persisted with this stance then Mr Porter would advise the Governor-General that Mr Turnbull’s position in relation to the Governor-General’s exercise of his powers was “wrong at law”. Mr Turnbull shot back, “You do not have any role advising the Governor-General” — a point that Mr Porter accepted.

Mr Turnbull told Mr Porter at the start of their meeting that “the Governor-General would not commission” Mr Dutton if he was elected leader of the Liberal Party — because of doubts about Mr Dutton’s eligibility to sit in the parliament due to an alleged conflict with section 44 (v) of the Constitution, relating to his wife’s childcare business receiving a government subsidy.

The inference in Mr Turnbull’s remark was obvious — that he had already spoken to Sir Peter.

Mr Porter asked Mr Turnbull the obvious question: “Has the G-G told you this?”

Mr Turnbull avoided any direct answer. “I know the Governor-General and I know this would be his position,” he said.

In the end, Mr Dutton’s failure in the partyroom averted the lurch into a potential political and constitutional drama.

If Mr Dutton had been elected leader and advised the Governor-General he should be commissioned as prime minister, would Mr Turnbull — as the deposed Liberal leader but still the prime minister — have advised Sir Peter that Mr Dutton should not be commissioned? Or was he merely using the role of the Governor-General as a further argument to sink Mr Dutton’s challenge?

The previous day, Senate leader Mathias Cormann became alarmed at a meeting with Mr Turnbull when the prime minister made the same claim — that the Governor-General would not commission Mr Dutton — and motioned to ring Sir Peter directly to get the Governor-General on the phone to confirm this.

“He can tell you himself,” Mr Turnbull said to the delegation of senators Cormann, Mitch Fifield and Michaelia Cash, who had come to tell Mr Turnbull he had lost the confidence of the party.

“Let’s not be crazy, we don’t need to involve the Governor-General,” Senator Cormann said. “Let’s just work this through.”

Senator Cormann felt that Mr Turnbull was serious — that this wasn’t bravado, that he was actually ready to ring Sir Peter. The senator believed that he had probably averted the phone call.

Any such call would have been extraordinary. But it also left another impression: that Mr Turnbull must have already discussed this issue with Sir Peter, the view that Mr Porter initially formed.

When the same delegation saw Mr Turnbull the next morning to tell him they were resigning, he again raised the spectre of the Governor-General, without offering to phone him. One senior Liberal said: “The Governor-General was a constant theme for him.”

Yet the real tussle was played out between Mr Turnbull and Mr Porter. Mr Turnbull declined to comment this week when asked about his dealings with the Governor-General and Sir Peter’s potential role in the crisis.

This issue, along with Mr Turnbull’s own account of his private talks during the crisis, will be in his book when it is released next year. But one aspect is clear: Mr Turnbull as prime minister felt he had an obligation to raise the serious risks arising from doubts about Mr Dutton’s eligibility.

The dynamics of the Porter meeting were apparent: Mr Turnbull as prime minister was trying to recruit Mr Porter as Attorney-General to accept his view of the Governor-General’s role. Mr Porter was unswayed in his rejection.

Mr Porter told him: “If you want my resignation I will offer it.”

Mr Turnbull replied with heavy sarcasm: “Oh no, I wouldn’t want to lose my loyal Attorney-General.”

During their meeting, Mr Porter told Mr Turnbull there were two issues at stake. The first was whether it was wise or unwise to elect a leader who had a section 44 risk against him.

The separate question was whether the Governor-General could decline to commission a leader in that situation.

On this matter, Mr Porter was precise: he said the only test the Governor-General should apply was whether the new leader had the confidence of the house.

“Everything else is irrelevant,” Mr Porter said, meaning the section 44 risk. But Mr Turnbull, summoning every instrument to save his leadership, wasn’t accepting Mr Porter’s line, at one stage telling him: “Well, my learned friend, you would be wrong.”

Asked by The Australian whether the Governor-General had been involved in any discussion with Mr Turnbull or was forewarned about pending advice, a spokesman for the Official Secretary said: “Conversations between the Governor-General and the prime minister are necessarily private and confidential.

“I can, however, confirm that no formal advice was sought or provided to the office in relation to any eligibility issues.”

The confrontation

Both Mr Turnbull and Mr Porter stood during their 10-minute exchange. At one point, an angry Mr Turnbull complained that people such as Mr Porter and others had been weak and had capitulated to Mr Dutton.

Mr Porter told Mr Turnbull he wouldn’t be lectured to — but their relations had been fraught since their meeting the previous day, Wednesday, August 22, when Mr Porter offered his view of the leadership.

“My inescapable view is that you can’t win,” he told Mr Turnbull. “In my view you should resign because you have lost the confidence of the party.”

An agitated Mr Turnbull told Mr Porter he was only in this position “because people like you have given in to political terrorism”.

Rejecting this, Mr Porter said he had played no role in events leading up to the crisis. It was “unfair” to accuse him of giving into terrorism. Mr Porter said he was giving Mr Turnbull his assessment of the situation — with Mr Turnbull on the Tuesday having held off Mr Dutton only 48 votes to 35 in the partyroom.

The first spill

Senator Cormann had been shocked at Mr Turnbull’s decision on the Tuesday to spill the leadership without consulting the leadership group and felt Mr Turnbull had doomed himself from then.

During the Wednesday and following a request from Mr Turnbull’s office, Mr Porter had decided the correct course of action for him as Attorney-General was to seek an opinion from Solicitor-General Stephen Donaghue QC on Mr Dutton’s eligibility — but the circumstances surrounding this opinion provoked their own tensions between Mr Turnbull and Mr Porter.

The prime minister and the Attorney-General agreed that the request for the opinion must only come from the Attorney-General. They agreed that the Solicitor-General’s opinion was appropriate and inevitable given the circumstances.

But Mr Porter made clear he would formulate the terms of the request — a critical matter — without reference to Mr Turnbull.

Subsequently, when the Solicitor-General told Mr Porter on the Thursday morning that he had been contacted by Mr Turnbull, an annoyed Mr Porter, who believed this was in breach of their understanding, decided to formalise the process.

The letter

He drafted a letter to Mr Donaghue saying that neither members of the executive government nor the parliament were to contact or correspond with the Solicitor-General in relation to his advice on Mr Dutton (this formula covering Mr Turnbull as a minister and Mr Dutton, now a backbencher).

In the crisis week, Mr Porter had several critical discussions with West Australian colleague Senator Cormann.

Their talks covered the possibility of Mr Turnbull resigning on the Wednesday, though that did not happen.

At question time on the Wednesday, Labor asked about Mr Dutton. Then Labor leader Bill Shorten, keen to make political capital, asked Mr Turnbull to refer Mr Dutton to the High Court to test his eligibility. Mr Turnbull stonewalled. But the issue was running and had to be confronted.

After question time, an official from Mr Turnbull’s office came to see Mr Porter. He asked for a request to the Solicitor-General for an opinion on Mr Dutton’s position. Mr Porter said he would consider the issue.

But the discussion was on the basis that any opinion would be requested by the Attorney-General, not the prime minister. Mr Porter agreed — he said the decision lay with him.

A short time later, Mr Porter concluded that an opinion was essential, given the situation. He walked down to Mr Dutton’s office and told the MP that Mr Turnbull’s office had requested an opinion from the Solicitor-General on Mr Dutton’s eligibility as an MP.

Mr Porter informed Mr Dutton that he had independently decided this was the best way to proceed. It was important that Mr Dutton co-operate. Mr Porter said he would ensure the process was procedurally fair to Mr Dutton.

The delegation

That afternoon, Senator Cormann told Mr Turnbull he should resign and visited his office with ministers Senator Fifield and Senator Cash, who offered their resignations and said Mr Turnbull had lost the support of the party.

Senator Cormann believed Mr Dutton had majority support, and they were backing him.

That evening, Mr Turnbull called Mr Porter to his office — they spoke about the leadership and Mr Dutton’s eligibility.

At this point, Mr Porter took the same position as the Cormann delegation — Mr Turnbull couldn’t win and should resign. The West Australians were overwhelmingly against Mr Turnbull and for Mr Dutton.

“It should be my task alone to deal with the Solicitor-General’s opinion,” Mr Porter told Mr Turnbull.

“I should formulate the request and the terms.”

This was not just correct procedure; it was also a necessary protection for Mr Turnbull to be at arm’s length from the process. They reached an apparent agreement on this. It was a tough meeting but contained.

Mr Turnbull sat at his desk throughout. That evening Mr Porter contacted Mr Donaghue and sent him the documents.

On Thursday morning, Mr Porter woke to a host of messages. The Solicitor-General reported that Mr Turnbull had contacted him — the prime minister wasn’t overbearing but he wanted details on the timing of the Solicitor-General’s advice and the nature of the request.

That provoked Mr Porter’s decision to formalise the process and deny others access.

Mr Donaghue subsequently reported that Mr Turnbull had “tried to reach me again” but he did not respond. Here was a situation: a Solicitor-General ignoring a prime minister!

Meanwhile, Mr Dutton visited Mr Turnbull just after 7.30am, requesting a party meeting at which he would challenge for the leadership. The climax was coming.

The late tactic

A short time later, Mr Turnbull and what was left of his leadership group agreed on the tactic of demanding 43 signatures from Liberal MPs — a majority — before convening the partyroom meeting on the leadership.

In the end, this was to prove decisive. It was one of two instruments Mr Turnbull was using to stop Mr Dutton.

Mr Porter was engaged with the other. That morning, he convened a meeting with officials from the Australian Government Solicitor and from his own department.

The subject: the Governor-General and his powers in commissioning a prime minister.

Mr Porter knew he would get an opinion about Mr Dutton and that Mr Turnbull, unsurprisingly, wanted to use that opinion against Mr Dutton, arguing he could not become prime minister if there was a doubt about his eligibility to sit in the parliament.

Mr Porter wanted to cover every eventuality.

Legal opinions are rarely black and white. Mr Porter’s experience told him the Solicitor-General would probably find a risk in relation to Mr Dutton’s eligibility but also felt his overriding “better view” would be to clear Mr Dutton.

Indeed, this had been the assessment Mr Porter offered Mr Turnbull at their meeting the previous evening.

While requesting advice from officials about the Governor-General’s role, Mr Porter made his own views clear — he felt that “uncertainty over section 44 (v) could never be the basis on which the Governor-General could decline to commission a new leader”.

Mr Porter was adamant in this view. The officials agreed. They gave oral advice and prepared written advice.

That morning, Senator Cormann rang Mr Porter — he reported that Mr Turnbull had told him that Mr Porter had advised that Mr Dutton was ineligible to sit under section 44 and should be referred to the High Court.

Mr Porter informed Senator Cormann of his actual view.

What was happening? Was Mr Turnbull verballing Mr Porter with Senator Cormann in order to turn the tide or had somebody got their wires crossed in transmission?

At 10.10am, a move by the manager of opposition business, Tony Burke, to refer Mr Dutton’s eligibility to the High Court was defeated on the floor of parliament in a critical 69-68 vote.

Ahead of the prime minister’s afternoon press conference, Mr Turnbull and Mr Porter had their crucial Thursday meeting and showdown over the potential role of the Governor-General in the crisis.

This is where Mr Turnbull was emphatic with Mr Porter that Sir Peter would not commission Mr Dutton — even though the Solicitor-General’s opinion was not yet available.

As they talked, the pivotal question hung in the air: had Mr Turnbull spoken to Sir Peter or was he merely trying to convince Mr Porter to draw this inference?

Penultimate stand

At the press conference, Mr Turnbull pulled back substantially from what he told Mr Porter. The prime minister made the obvious point that any new Liberal leader would need to have the confidence of the house — and clearly Mr Turnbull had doubts about Mr Dutton on that score.

Then Mr Turnbull said: “In the case of Mr Dutton, I think he’ll have to establish that he is eligible to sit in the parliament. I mean, again, I don’t want to elaborate on this any more than I need to, but this issue of eligibility is critically important.

“You can imagine the consequences of having a prime minister whose actions and decisions are questionable, because of the issue of eligibility, ie are they validly a minister at all?”

Mr Turnbull made no statement to the media about the Governor-General’s attitude or his belief that Mr Dutton should not be commissioned.

That night, Mr Porter drafted a document for use in the partyroom the next day, expecting questions on Mr Dutton’s status.

Judgment day

On the morning of Friday, August 24, the Solicitor-General briefed Mr Porter on his opinion. During the morning the Attorney-General received two documents — the opinion, which he felt “was as conclusive as possible” in clearing Mr Dutton, and the Australian Government Solicitor’s advice on the Governor-General’s role.

The Donaghue opinion concerned whether Mr Dutton — because his wife’s childcare business received a government subsidy — might have a “direct or indirect pecuniary interest” in an “agreement with the public service of the commonwealth”. The Solicitor-General said there was “some risk” but that the “better view” on the facts was that Mr Dutton was “not incapable” of sitting as an MP.

Mr Porter sent copies of the opinion to Mr Turnbull and Mr Dutton simultaneously. He attached his own note on the opinion for Mr Turnbull, setting out his views on the role of the Governor-General — namely that Sir Peter could act only on the issue of confidence, not on any section 44 position. Mr Porter wanted his own view documented for the record.

Mr Turnbull had a real concern with Mr Donaghue’s opinion. He believed the facts of the matter relating to Mr Dutton were more serious than the Solicitor-General’s opinion conceded. He felt there was no question whatsoever that there was a serious doubt about Mr Dutton’s eligibility.

Meanwhile, Mr Porter got his chief of staff to contact Government House with a message — Mr Porter was available to speak to the Governor-General if Sir Peter felt the need. That is, Mr Porter was ready to offer an opinion if the Governor-General ended up as the recipient of conflicting advice from Mr Turnbull and Mr Dutton.

The conclusion

In the partyroom, the issue never arose. The motion to spill the leadership and terminate Mr Turnbull’s leadership was carried 45-40. It was tight: just three votes made the difference. In the final round of the leadership contest Scott Morrison beat Mr Dutton 45-40, again a tight result.

With Mr Dutton’s defeat by Mr Morrison, any debate about the role of the Governor-General was also terminated. Mr Morrison was sworn in as Prime Minister by Sir Peter in the conventional manner.

What might have happened if Mr Dutton had been elected remains speculative but the best speculation is surely that the Governor-General would have commissioned Mr Dutton in the usual way — as Mr Porter had argued and despite Mr Turnbull’s claims to the contrary.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout