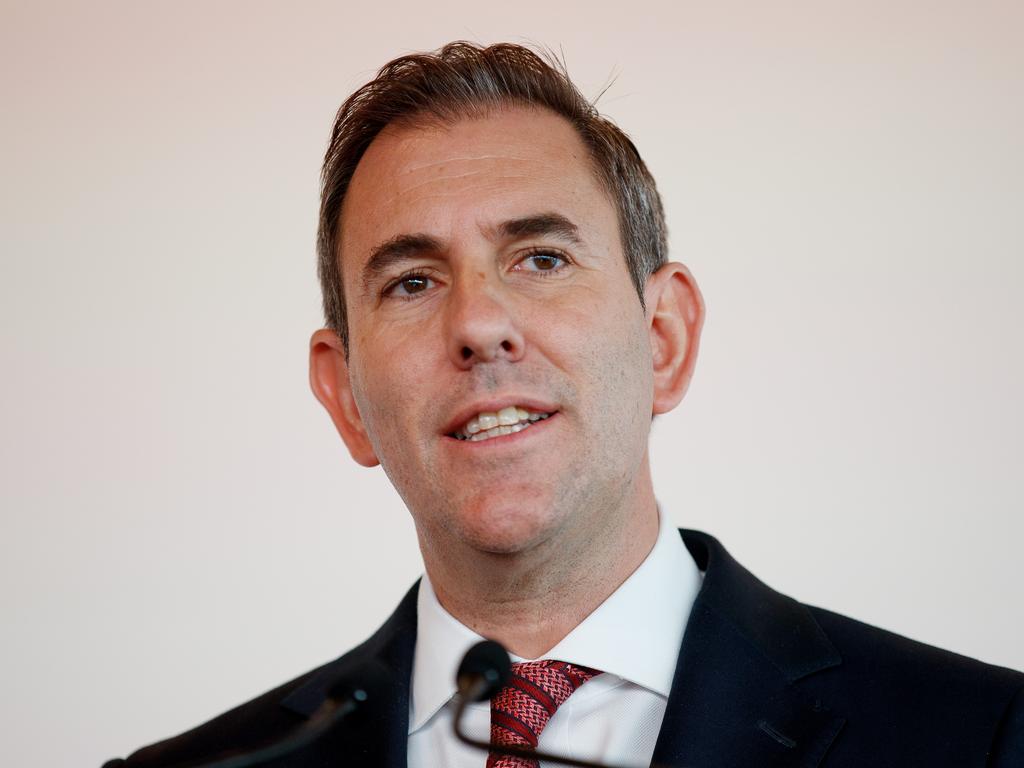

Treasurer Jim Chalmers appears to be ignoring the inflation elephant in the room as budget looms

This is remarkable considering that from a political perspective, there is no issue of greater concern to most households.

Instead, the Treasurer appears locked in to a growth story that he and Anthony Albanese pivoted to earlier in the year.

This may have been the right call at the time. Not so much anymore, according to some economists.

Considering the data of the past six weeks, alarm bells are starting to ring over whether the budget is going to continue the relative discipline of the past two years or start to make things worse. A seeming lack of agility, or will, to recalibrate has raised concerns.

Two weeks from budget day, Chalmers mentioned cost of living just once on Tuesday in his major set piece on the economy. He references inflation seven times, but in a tone that is almost taking on a historical context.

“It worries me that there was this pivot in the narrative, that inflation is still the priority but we now need to support growth,” says economist Warren Hogan, who is regarded as one of the leading economic forecasters.

“We are starting to wander off the narrow path. We are doing better than the RBA forecasts, creating more jobs, but the RBA needs to keep the economy soft for an extended period.”

Hogan has forecast a return to rate rises for later this year, but has arrived at this conclusion earlier than most.

The bond markets appear to now be in agreement, factoring in at least one small rate increase in October.

The opposition has rightly jumped on inflation as the key test for Chalmers in the budget.

Chalmers is under pressure to provide some cost-of-living relief. But if the budget doesn’t contain new spending to less than half a per cent of GDP, says Hogan, then the RBA may have to tap the brakes again early next year – just before the next election.

The political consequence of such a scenario needs no illumination. The consensus among economists is that the Albanese government went too early on the growth story when it switched gears earlier this year. At the time it appeared that this may have been the right strategy.

All that has changed, according to several leading economists, Hogan included.

And all the signs over the past month suggest significant danger remains.

Bob Hawke understood that inflation changes politics, and that Labor in the 1980s needed to change with it. It is less clear whether Chalmers is a disciple of this thinking.

Herein lies the problem. The central bank needs the economy to be soft for an extended period to get inflation under control. Chalmers is talking about growth.

In his defence, the type of growth Chalmers is talking about is long-run investment. No one believes that the Future Made in Australia agenda is going to add to the inflation problem in the short term as it is unlikely to pump any real new money into the economy between now and the end of the year.

But as KPMG claimed this week, there was now a serious misalignment between the central bank and fiscal policy. Economist Chris Richardson points to the $12bn in extra net spending this financial year alone. Hogan points to the $22bn in tax cuts that will start hitting the economy in July. At the same time, there is a stunning absence from the government in the framing of this budget as a response to the cost-of-living crisis beyond these tax cuts.

It’s as if Chalmers and Albanese think they can ride out the problem until the election and then deal with it later.

Hogan says what was troubling about the most recent inflation numbers was that domestic inflation was a very real problem and was now running at 4 per cent.

While he believes the government had been disciplined so far, any new money into the economy is going to make the RBA’s job harder.

The risk for Chalmers is that the economic security story he is weaving for the budget is overtaken by an assessment of the budget as being part of the inflation problem.

A lack of rhetorical urgency around inflation and cost-of-living pressures is emerging in the framing of Jim Chalmers’ budget strategy.