Tony Eggleton was the valued and trusted close adviser to five PMs

Tony Eggleton was the only member of Harold Holt’s staff to make the transition to John Gorton’s prime ministership. It would test him.

Australian politics has lost one of its most influential and decent practitioners. Tony Eggleton, who died aged 91, was unrivalled as a confidant, adviser and organiser serving five Liberal prime ministers and exercising an unparalleled role in the history of the federal party organisation.

Eggleton was a brilliant migrant success story to Australia from Britain. In a remarkable career he was renowned for his competence, trustworthiness, calmness under pressure and sound judgment in advising Liberal prime ministers from Robert Menzies to John Howard.

His career as a Liberal official is unmatched. Howard said in his tribute that Eggleton was “indispensable to the history of the Liberal Party”. In a long career dealing with two generations of political journalists, Eggleton achieved a rare feat: winning almost universal acclaim for his professionalism. He was federal director of the Liberal Party from 1975 to 1990.

Eggleton became privy to many of the deepest secrets in Australian Liberal politics with discretion being his hallmark. He was a loyal Liberal but also a proud Australian who served in many capacities. He was skilled in advising political power and operated with integrity in a domain where integrity was in constant peril.

Educated at King Alfred School at Wantage, England, Eggleton from age 15 became a young reporter on his local paper in Swindon. The turning point in his life came early – the chance to move to Australia to work for the Bendigo Advertiser as a D-grade journalist. He sailed from Southampton in March 1950 to a country where he knew almost nobody.

He soon got a position with the ABC in Melbourne, and met and married a kindergarten teacher, Mary Walker. ABC editor-in-chief Wally Hamilton said Eggleton was “a journalist of exceptional ability” and soon he was involved in the introduction of ABC television.

In 1960 the second turning point in his life came when Eggleton won a position in naval public relations, being interviewed at one point by navy minister John Gorton. Their subsequent encounters would make history. Eggleton became a suburban pioneer in Canberra. His qualities of diligence and disposition made him invaluable in the role.

In 1964, the aircraft carrier HMAS Melbourne collided with the destroyer HMAS Voyager and Eggleton dealt with the media and organised press conferences, bringing him into contact with prime minister Menzies.

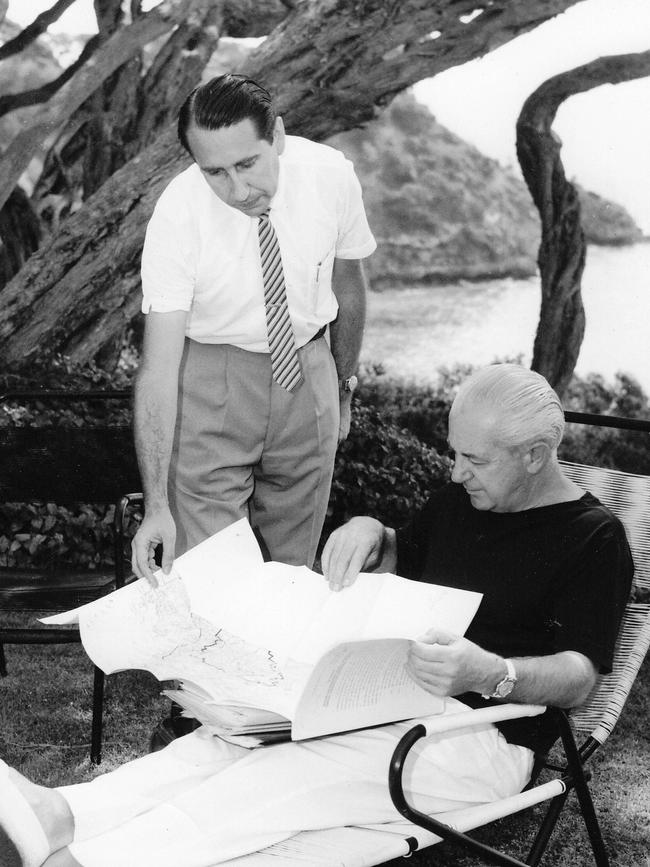

Menzies decided he wanted Eggleton for himself. In September 1965 Eggleton met Menzies in the prime minister’s office and found he was being referred to as “laddie”. Aged 33, he became press secretary to Menzies, aged 70. Menzies’ decision would shape Liberal politics for decades.

Eggleton typically was seen sitting in the rear of Menzies’ Bentley. As Menzies confidence in Eggleton grew, he allowed him to brief the media on his behalf and invited Eggleton to spend the Christmas 1965 break with him, confiding his intention to retire, a sign of total trust in Eggleton. Eggleton supervised the historic Menzies retirement media conference of January 1966. In a short time there was a knock on Eggleton’s hotel door – it was prime minister-elect Harold Holt, clad only in underpants, seeking advice. So began the Holt era.

Holt kept Eggleton in the job. He said he wanted “friendly” relations with the media. Indeed, Holt wanted Eggleton by his side. For Eggleton the job expanded – the media was more pushy and there was an international dimension as Holt formed a personal relationship with US president Lyndon Johnson.

Eggleton became Holt’s political adviser as the Liberal Party began to fracture. Eggleton was cool, unruffled, understated. His manner assured often anxiety-prone prime ministers. Eggleton warned Holt about water sports but Holt laughed, asking what were the odds of a prime minister “being drowned or taken by a shark”.

Quite high, it proved. On December 17, 1967, Holt disappeared in the surf at Portsea on Victoria’s Mornington Peninsula. Eggleton became a national figure. He presided at a series of televised press conferences from the Portsea army base with much of the nation fixated. He later lamented in private that Holt had a “show-off” streak and a “fatalism” in him.

Eggleton was the only member of Holt’s staff to make the transition to John Gorton’s prime ministership. But this would test all his skills. Journalist Alan Reid said Eggleton was “loyally struggling” to present Gorton to the Australian public since Gorton insisted on living a “normal life” when Eggleton knew this was untenable.

Gorton’s relationship with his young senior private secretary, Ainsley Gotto, became a public soap opera. Eggleton later wrote in private of Gorton: “If he is not man enough to do without her, then he must fall with her.” At one point Gorton carried a personal firearm on an overseas trip, causing immense worry for Eggleton. He had to manage Gorton’s recklessness.

The nadir came on November 1, 1968, when Gorton was guest of honour at the annual press gallery dinner and word came the US ambassador needed to brief him on Johnson’s Vietnam decisions. Gorton was drinking, invited a young journalist, Geraldine Willesee, to join him and in the car had an aggressive exchange with Eggleton – who was trying to protect him – saying he would not be told what to do. In reply, Eggleton said: “It would take a better man than me to protect you.” When they got to embassy, with Gorton holding Willesee’s hand, farce turned into weeks of political horror.

Eggleton was appalled at Gorton’s laziness during the 1969 campaign, with Eggleton locked in last-minute improvisations to “save” him. While journalist Max Walsh said Eggleton had become a “one-man intelligence network”, Gorton was beyond saving. After being offered the job as director of information at the Commonwealth Secretariat in London, Eggleton accepted. Decades later in a private note, Eggleton said he knew Australia would be better off “without this man as prime minister”.

He stayed briefly to help the new prime minister, William McMahon. At one of the many farewells, press gallery president Allan Barnes said Eggleton was the best press officer he had known. Graham Freudenberg said Eggleton had elevated the standing of press secretaries.

A few years later the new Liberal leader, Billy Snedden, persuaded Eggleton to return to Australia to assist him and the party. Eggleton was thrown into the turmoil of the Liberal defeat at the 1974 election, the leadership crisis and the subsequent Fraser era. He became Liberal Party federal director under Fraser and served in the post under Andrew Peacock, Howard and Peacock again. Some Labor figures were silly enough on his return to suggest that Eggleton was “yesterday’s man”. The Fraser-Eggleton team delivered Liberal election victories in 1975, 1977 and 1980.

In late 1975 Eggleton attended and kept records of the shadow cabinet meetings during the most intense constitutional crisis since Federation. His notes showed that while state divisions were worried, the longer the crisis continued the more determined were Fraser and the leadership group.

When Fraser returned from Government House at lunchtime on November 11, 1975, it was Eggleton, aware of what had transpired, who met his car and said: “Welcome, prime minister.” Eggleton rejected claims the crisis and Gough Whitlam’s sacking had prejudiced Fraser’s prime ministership. He was emphatic that the dismissal did not overshadow Fraser’s governance. “I don’t think it poisoned his approach or thinking,” Eggleton said.

Fraser built an impressive power structure as prime minister in governing and party terms. Eggleton as federal director, was pivotal in that model. Given his temperament, experience and judgment, this was Eggleton’s perfect job. He knew his place was always important with Fraser. Eggleton told this writer his philosophy was “always be ready for a campaign”. Laurie Oakes said Eggleton was “an expert at putting out fires”. Eggleton was not a deal-maker, not a policymaker. He was a trusted adviser to Fraser and manager of the federal party. He had limited formal power but huge informal influence. That’s how he thrived. During this period he was without peer as a political strategist in national politics.

Fraser was unaware of the full extent of the assistance he received from Eggleton, who briefed the senior political correspondents, often putting forward more plausible accounts of the government than coming from Fraser himself. Yet Eggleton never lost his journalistic perspective. On occasions, when pressed, he would confirm stories not in the government’s interest but in a wider public interest.

He was a person of loyalty and principle. The Liberal Party has never enjoyed a more diligent official, but he had a wide vision and felt an obligation to his country.

Fraser and Eggleton met their match in 1983, outsmarted by a superior ALP and a superior leader in Bob Hawke. Eggleton incurred much criticism but the incoming leader, Peacock, insisted he remain in place. After the 1983 defeat, Eggleton remained federal director for the losing campaigns of 1984, 1987 and 1990 – the Hawke era and the formidable ALP machine. These were troubled years marked by the Peacock-Howard rivalry and internal turmoil. Howard said Eggleton was an “invaluable” adviser to him during his first leadership period, which was also burdened by the “Joh for PM” lurch.

After the 1990 defeat Eggleton, with Fraser’s assistance, went international again – becoming secretary-general of CARE International, a private international humanitarian organisation. Just short of his 60th birthday he moved into an entirely new career requiring extensive diplomatic skills.

Eggleton had an active retirement living in Canberra. From 1997 he was chief executive for the Centenary of Federation planning committee, working at close quarters with former NSW Labor minister Rodney Cavalier, who was his deputy in a highly productive partnership that made a significant contribution to the 2001 celebrations and events.

From 2002 to 2007 he was chairman of the CEW Bean Foundation and was a key figure in developing the war correspondents’ memorial in Canberra. His wife Mary died in 2015, aged 87.

Reid called Eggleton “a very proper man”. On his retirement he was praised for his professionalism by senior journalists from Walsh to Rob Chalmers.

Eggleton dedicated much of his life to the Liberal Party yet the party did not define him. He had respectful relations across the political divide and never forgot his role as a journalist. He was the ultimate political professional.

Eggleton is survived by his three children and their families.

This draws on the biography by Tom Frame A Very Proper Man: The Life of Tony Eggleton.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout