The election just got harder for the ALP, and rightly so

Anthony Albanese’s conviction on China cannot be questioned? What rot. Labor cannot whitewash its actions and records.

In this environment, politicians and journalists want to smother debates on national security – yet without national security, little else matters.

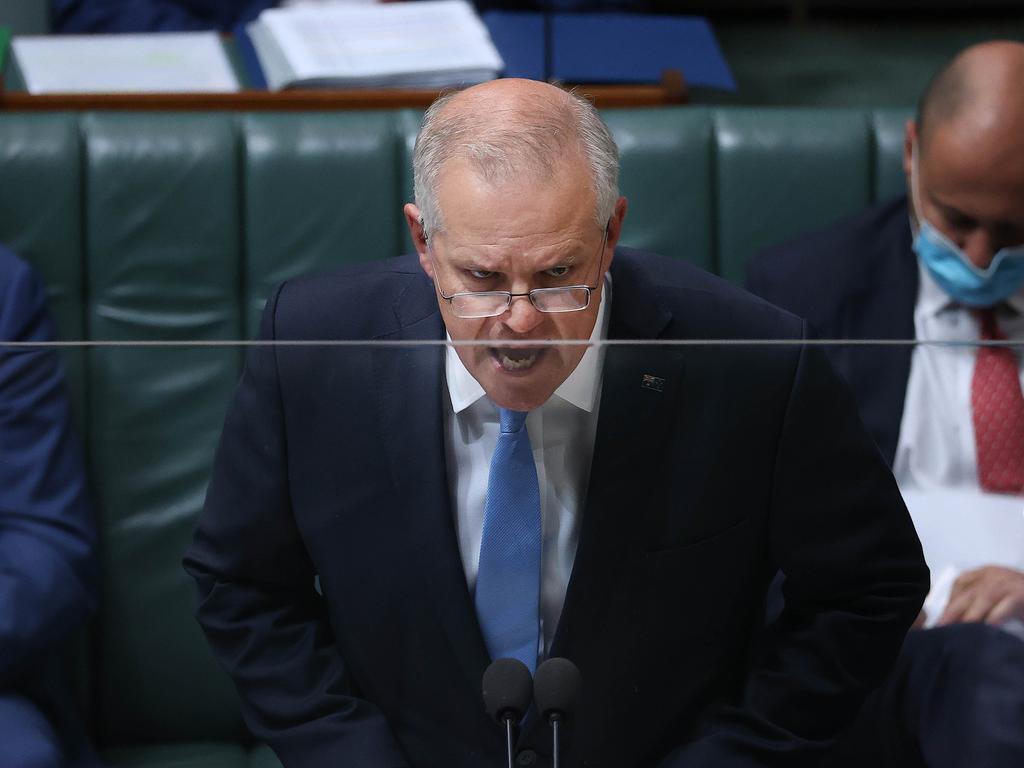

Australia’s most crucial pandemic decision was one of national security; Scott Morrison’s closure of our international borders and imposition of mandatory quarantine kept the nation virtually virus free until vaccines arrived. All the rest – over two years of overreach, paranoia and posturing by state governments – was piffle by comparison.

For all the complexities and frustrations of our federation, national security is the clear domain of Canberra. It is why we have a federation. Little wonder, then, that national security should figure prominently in federal campaigns. Leaders or parties that cannot be trusted on national security rule themselves out of the contest.

Yet this month a rearguard action by politicians, former bureaucrats and journalists has attempted to shield Labor from scrutiny over China, accusing the government of going too far in seeking to identify Labor acquiescence. Our relationship with China is not only a legitimate campaign issue, it is one of the most pressing.

If there is a challenge more important than managing our trade and security relationship with China, while maintaining our alliance relationship with the US and fruitful engagement with the rest of East Asia and the Pacific, then I am yet to hear about it. Most other tests – energy security, manufacturing self-sufficiency and defence capability – play into it.

Yet the proposition put by Labor and amplified by commentators is that because the ALP has endorsed government positions on the South China Sea, pandemic origin inquiries and the quadrilateral dialogue, Anthony Albanese’s conviction on China cannot be questioned. What rot; in politics, as in life, words are cheap, and they cannot whitewash actions and records.

Labor has long claimed a bipartisan approach on China while sniping at the government’s performance and blaming the Coalition for tensions with Beijing. When economic sanctions, diplomatic boycotts and military intimidation are in play and you blame the Australian government for the rift, you are not being bipartisan – you are supporting Beijing’s case against Australia.

In November last year, Penny Wong (who would be foreign minister in an Albanese government) blamed the Prime Minister for Sino-Australian tensions. “It is true China has changed, and our relationship has become harder to manage,” Wong told the ANU, “but desperately playing politics on China whenever he is in trouble does nothing to strengthen Mr Morrison’s authority with Australians or Beijing.”

Diplomats at the Chinese embassy in Canberra would have scrambled to send a cable to Beijing, eager to be first with the encouraging news that Australian politicians were blaming their own country for bilateral problems.

A year earlier, Labor’s most recent foreign minister, Bob Carr, told the South China Morning Post that “Australia’s tilt against China began in early 2017 under the prime ministership of Malcolm Turnbull”. Really? Australia turned against China? Thanks Bob.

“On the management of the Covid inquiry, on the management of Covid, and the inquiry, and on Huawei,” Carr continued, “I think we could have used diplomacy and not positioned ourselves so that everything, every inflection took on an anti-China dynamic.”

In a free country anyone has the right to criticise their own country rather than a communist protagonist. But it stretches credulity to do so and simultaneously claim bipartisanship.

There are many examples. Former Labor prime minister and foreign minister Kevin Rudd also had blamed his own country.

“The Australian government in my own judgment has not played this particularly well. Sometimes when China has been excessively assertive, the Australian government often responds rhetorically to cater to its own domestic political constituency,” Rudd told Bloomberg last November.

Only five years ago, Labor senator and factional powerbroker Sam Dastyari was exposed for allowing Chinese interests to pay his personal bills while he publicly echoed China’s foreign policy arguments. Dastyari even warned one of his Chinese confidantes he could be an ASIO target.

Since then, former Labor prime minister Paul Keating has advocated a more accommodating approach to China, saying Australia should avoid any conflict over Taiwan because it was not a “vital Australian interest”.

Yet the Canberra consensus suggests none of this record should be used in the contemporary political debate to discredit Labor’s claimed conviction and bipartisanship on China.

Apparently, Albanese and Labor should be given the eternal sunshine of the spotless political mind on China – we should ignore what Keating, Rudd, Carr and Wong have said, and what Dastyari has done, and pay attention only to what Labor promises on the cusp of the election.

In 2007, after a decade of condemning the Coalition’s border security policies as inhumane and unnecessary, Rudd promised to replicate them, including turning back boats, if he won. “You’d turn them back,” he told this newspaper.

After winning office Labor refused to turn boats back, lost control of our borders and unleashed a humanitarian disaster that churned more than 50,000 people through mandatory detention and cost at least 1200 lives. So much for words.

Showing more chutzpah than the teenager who kills his parents and pleads for mercy as an orphan, Rudd has criticised the Coalition for being divisive on foreign affairs. “You see there is only one country advantaged by an artificial division in Australia, a bogus division on national security policy,” Rudd told the ABC. “And that is the People’s Republic of China itself.”

Yet in Rudd’s final months as prime minister, he pursued a dangerously inflammatory foreign policy attack. It was six years after Rudd promised to turn boats back, there was border chaos, and he was then running the argument that it was impossible to safely turn boats around.

“I’m very concerned about whether, if Mr Abbott were to become prime minister and continues that rhetoric and that posture and actually tries to translate it into reality,” Rudd said in 2013, “I really wonder whether he’s trying to risk some sort of conflict with Indonesia.”

This was a sitting prime minister invoking the prospect of a conflict with one of our closest neighbours, based on a confected argument to advance his own partisan political agenda. As it happens, Rudd lost the election, boats were turned back, borders were secured and there was no conflict with Indonesia.

Yet the Rudd criticism of the government now, self-serving and intellectually bereft as it is, has been adopted by much of the Canberra press gallery. ABC TV news political reporter Andrew Probyn editorialised about the Coalition attacks against Labor: “It has the distinct scent of desperation, risking bipartisanship on national security for short-term domestic political advantage.”

Back in 2013 when Rudd raised the prospect of “conflict” with Indonesia, gallery veteran Michelle Grattan wrote that: “The opposition was predictably outraged. But it had got a glimpse of how toughly Rudd, despite his exhortation that political discourse needs to be elevated, will fight.” Spot the difference?

These media games, as usual, amount to little. Mainstream voters usually see through them. Whatever the political/media class wants to pretend, Labor will be viewed by many voters as suspect on national security because of its dealings with Chinese interests, its constant sniping at the government over what is supposed to be a bipartisan posture, and its record of pretending to have conviction on national security but failing to follow through.

How can it be fair enough to accuse Coalition parties of being strident, obstreperous or hawkish on international affairs, but unfair to accuse the Labor side of being squeamish, acquiescent or dovish?

The public, as ever, will be more realistic. They will want their nation to stand up to China, and they will have their doubts about Labor.

As Paul Monk wrote in these pages last weekend: “One issue ought to be uppermost in the minds of voters: the future of our national security policy and our relations with China. Our economic future, our political future and our sovereignty are all at stake.” Even if the China debate does little to improve the Coalition vote or save the government, it will be beneficial for the nation. Because it will force Labor to commit strongly to current settings, making it more difficult to retreat in government.

Recent analysis of the national security impact on elections has tended to focus mainly on the Tampa affair in 2001. This overlooks the crucial significance of 9/11 just days later, a discombobulating episode that might have seen voters look to the Coalition government as reliable on security issues.

Three years later in 2004, Labor leader Mark Latham was hampered by his “troops home by Christmas” promise, and the deadly terrorist bombing of the Australia embassy in Jakarta underscored the importance of security just days out from the election.

In the big anti-Labor swings of 2010 and 2013, border security failures were more important factors than many appreciate. The China debate and the disgraceful Russian invasion of Ukraine will ensure that national security figures prominently in this year’s election.

This will increase the degree of difficulty for Albanese, and play to Morrison’s strengths.

We live in a mollycoddled age of denial where until recent days the chattering classes have been more interested in the rights of transgender athletes than the sovereign rights of 44 million people in Ukraine. The overstated threat of global warming receives more attention than the understated threat of totalitarianism.