If we have any consciousness at all of our own national interests, for the rest of our lives we will be worrying about how to counter Beijing’s influence, and in due course military presence, in the South Pacific.

There is no doubt this is an epic fail in Australian policy.

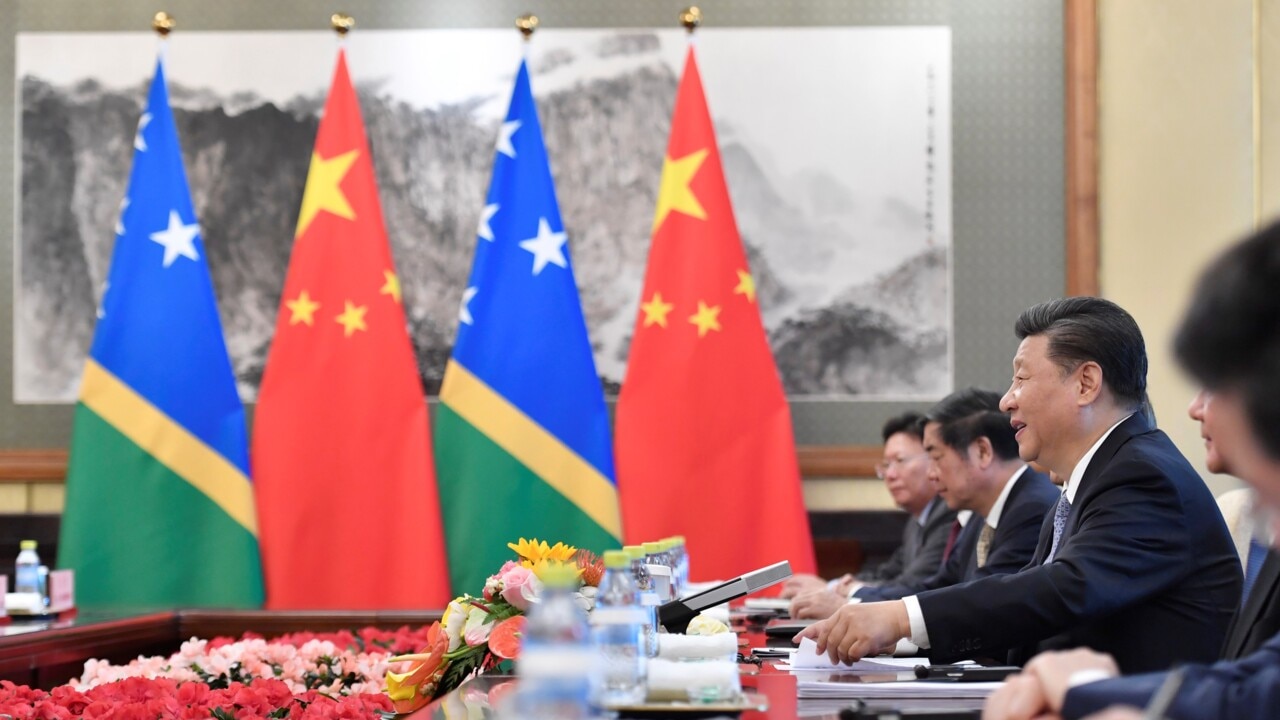

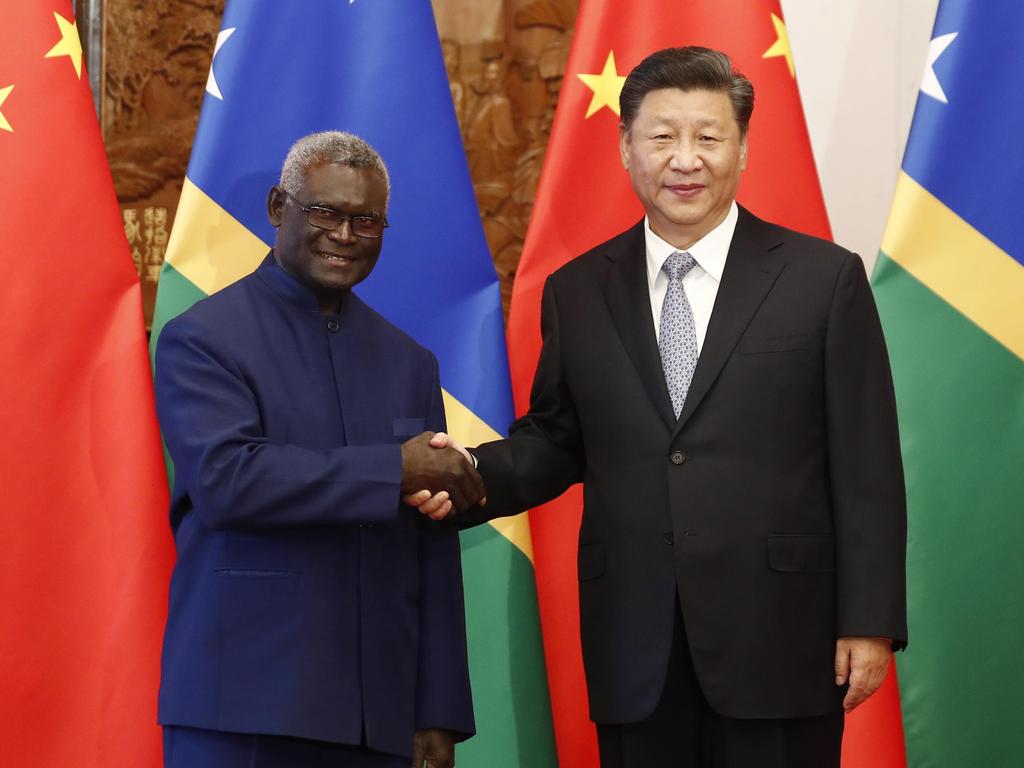

In a rerun of the Cold War, Australia, New Zealand and the US are competing for influence in the South Pacific, this time not with the Soviet Union but with China.

It was Australia’s very strong preference that this agreement not go ahead. It was Beijing’s preference the agreement proceed.

As a strategic competitor, Beijing was successful and Australia failed. There’s no getting around it. We failed, in a matter of fundamental importance to us.

The Solomons government says this agreement will not lead to a Chinese military base and is directed only at internal security and police training.

These assurances are better than nothing, but they are not worth much. Honiara is no match for Beijing in this sort of issue.

China has a long history of compromising client states through debt, political influence, economic sponsorship and ubiquitous presence.

Several nations that have ended up hosting Chinese facilities did not start out with the intention of doing so.

Aspects of Australian policy are baffling. Canberra knew at least since last August that this agreement was on the cards.

Julie Bishop, an immensely successful Coalition foreign minister, says Marise Payne should have visited the Solomons to make Australia’s case.

Instead, at the last minute, Canberra sent junior minister Zed Seselja.

Sending Payne may not have changed things but this is a matter of the highest importance for Australia. We should have sent the most senior minister to make the most persuasive case.

Beijing has some advantages. Canberra gives more aid to the Solomons than China does, but Beijing can put money directly into the pockets of Solomons politicians by funding the Constituency Development Funds.

Nonetheless, that kind of disadvantage in seeking influence in the Third World is an old Cold War story. It’s the sort of disadvantage smart democracies overcome, one way and another.

This is also an American failure. Washington has not had an embassy in the Solomons for nearly 30 years, yet the money involved in the US having a diplomatic presence there is less than the State Department loses down the back of a couch.

The US is about to reopen an embassy and is now sending Kurt Campbell, the Indo-Pacific Co-ordinator at the National Security Council, to the Solomons this week.

Campbell is much more senior in the US system than Seselja is in the Australian system.

But if we really are so close to the Americans as we are told, and have so much influence with them, how is it that Canberra has never convinced Washington in the past to re-establish an embassy in the Solomons?

It can only be that we never elevated the issue in our relationship with Washington.

This is allied failure all around.

Will we now at least have the wit to respond to the new strategic circumstances it announces?

The signing of the China-Solomon Islands security treaty is a very bad day for Australia, one of the worst days for our national security since the end of the Vietnam War.