Renewable energy target at risk as onshore wind farm endure onerous burdens, industry says

The PM will fail to hit his target of 82 per cent renewables by 2030, as slow planning and onerous environmental approvals are stymieing efforts to build enough green energy this decade, developers say.

Australia’s most powerful group of solar and wind farm developers say Anthony Albanese will fail to hit his target of 82 per cent renewables by 2030, as slow planning and onerous environmental approvals are stymieing efforts to build enough green energy this decade.

In a blistering declaration, the Clean Energy Investor Group – which represents companies such as Andrew Forrest’s Squadron Energy, Macquarie and French giant TotalEnergy – hit out at new federal guidelines for project approvals it warns would torpedo the Albanese government’s signature renewable target.

The Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water has issued a guidelines paper outlining a raft of measures required to get environmental sign-off on dozens of proposed wind farm projects, including a specific focus on their impact on “protected matters” such as birds and bats.

The investor group said the federal government’s renewable energy target would be “challenging to achieve” under the proposed guidelines, in a letter obtained by The Weekend Australian. “Securing environmental approval is becoming increasingly challenging, particularly for wind projects. While CEIG supports robust Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation assessments, the current administration of the EPBC Act remains a large issue for the energy sector.”

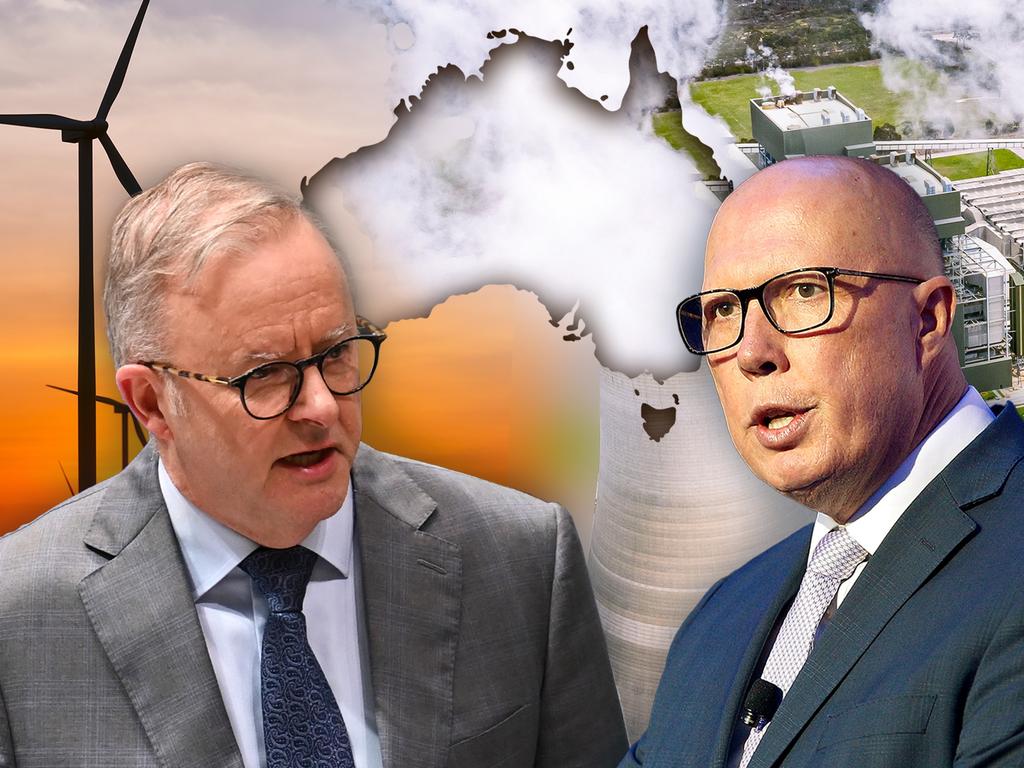

The rebuke by the energy players comes at a delicate time for Labor after a week-long political firestorm sparked by Peter Dutton’s pledge he would go to the next election opposing Labor’s 43 per cent carbon emissions reduction target by 2030 and declaring the goal unachievable.

The slower than expected rollout of both big renewable energy and electricity transmission projects to deliver green power to households has raised concern that Australia may need to wind back planned further closures of coal power stations to ensure the lights stay on, further clouding emission targets in the remaining part of this decade.

Climate Change and Energy Minister Chris Bowen this week challenged Mr Dutton to say whether he would take Australia out of the Paris Accord, an international agreement to combat climate change.

The Australian Energy Market Operator estimates the country needs 57GW of grid-scale solar and wind generation capacity to be installed by 2030 – a rise from the current capacity of 19GW. But planning remains so problematic that many wind farms take more than five years to secure planning and environmental approvals.

The investor group alone collectively has a 46GW pipeline of renewable projects to be rolled out in Australia but urged the government to rethink how it assessed wind farm developments or risk the target of 82 per cent by 2030 along with emissions goals.

Daniel Zelcer, interim policy director at the Clean Energy Investor Group, said: “The urgency of the climate crisis necessitates the accelerated development and deployment of clean energy projects. Delays in bringing these projects online not only hinder our ability to mitigate the impacts of climate change through the reduction of greenhouse-gas emissions, but these delays also postpone the economic and social benefits of transitioning to clean energy, including more affordable electricity for consumers.”

Mr Zelcer said the department must weaken its requirement that wind farm developers collect two years of avifauna surveys before they can then seek approval under the EPBC Act. Instead, Mr Zelcer said, developers should be mandated to collect one year of surveys. “This delay could lead to loss of position in the connection queue, expiration of landowner agreements, and other detrimental outcomes,” he said.

“Such setbacks will result in an inadequate number of projects gaining approval under the EPBC Act, thus delaying the clean energy transition and risking the federal government’s renewable energy target.”

The warning encapsulates Labor’s struggle to reconcile its renewable energy target with existing environmental standards. The tension has created unusual bedfellows, combining environmentalists with opponents to renewable energy in an attempt to block new wind farms.

Mr Zelcer said the government must, however, be forthright and frank. “The (Clean Energy Investment Group) advises that (the department) clearly communicate, through policy and decision-making criteria, that it is accepted that clean-energy projects will have some impacts in light of broader policy objectives,” he said.

Doing so, however, would be contentious. Many of Australia’s proposed wind farms are in environmentally sensitive regions, but if the country has any hope of rapidly weaning from coal to renewables it must embrace large-scale new developments.

A growing number of communities is heightening opposition to new developments and some states are moving to placate their concerns with higher standards.

Last year Queensland’s Labor government said it would require developers of wind farms to clear a higher threshold in order to secure licences amid local opposition, despite the sunshine state setting an ambitious target for transitioning away from its dependency on coal.

Queensland said it would strengthen environmental protections, increase rehabilitation requirements and require proponents to investigate the impact of their construction on workforces and accommodation.

While placating community concerns, any curtailing of onshore wind developments will further jeopardise federal Labor’s energy transition targets.

Authorities have admitted there must be an urgent uptick in renewable energy generation development if 2030 targets are to be met and enough new capacity is in place to allow for the orderly exit of coal.

Coal is the dominant source of Australia’s electricity, producing about 60 per cent of the nation’s power. But the traditional bedrock is rapidly waning and nearly all coal power stations are expected to close within 15 years, amid sustained economic and social pressure. Australia’s record proliferation of rooftop solar generation means wholesale electricity prices are often below zero, meaning coal power stations – which typically generate consistently throughout the day – are losing money. Coal can recoup losses in the evening when the sun has set and demand increases, but the rise of batteries has dented the capacity of traditional generators to remain profitable.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout