If we aspire to be a high-performance economy in coming decades, reform will have to be concentrated where the action is.

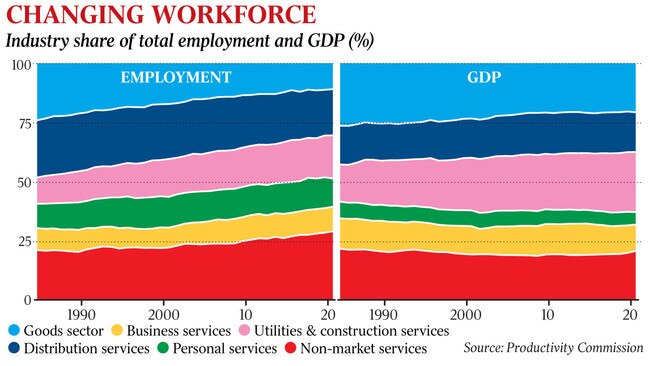

Encompassing all industries outside of mining, agriculture and manufacturing, the services sector is diverse, accounting for almost 90 per cent of employment and 80 per cent of gross domestic product.

A new report, Things You Can’t Drop on Your Feet, issued on Thursday by the Productivity Commission, is the first of many by the Morrison government’s key economic adviser that will inform bespoke policies to raise incomes.

The era of big-bang change is over, in part because politics decrees that lower taxes and workplace reforms are off-limits. The task now, almost four decades from the peak of the reform era, is vastly different.

Having revealed the high cost of industry protection and the benefits of liberalisation, the commission’s focus is trying to unlock the secrets of getting more value out of service industries, which have been smashed by COVID-19 and disrupted by digitisation.

“Behavioural changes in response to the pandemic, along with mandatory closures, have reduced face-to-face interactions, greatly increased the tendency to work from home and driven down or prohibited the use of some transport services,” the report says.

“This has translated to significantly lower demand for many services — particularly personal services (hospitality, accommodation, and recreation) and retail services.”

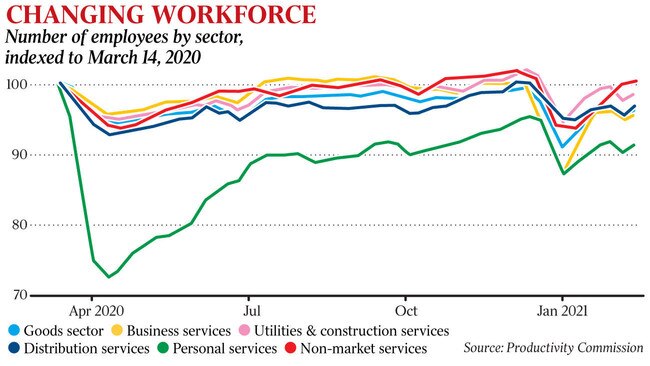

Between March and October last year, the personal services sector collectively lost more than 20 per cent of its workforce.

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, at the end of last month the number of payroll jobs across the broad economy was 1 per cent above its pre-pandemic level but still well down in key areas such as accommodation and food (9.5 per cent), information media (9.3 per cent) and distribution (6.4 per cent).

The commission noted that the rise of the service sector over the past 70 years, and the decline of manufacturing, has raised fears of worsening labour market conditions, slower wages growth and slower productivity growth.

Such fears are misplaced, it argues, because as incomes increase, we spend proportionately more on services relative to goods. This is true even for China.

As well, productivity growth in many services, including finance, ICT and transport, has outpaced the goods sector by a big margin in recent decades. Many service industries also have higher wages and total take-home pay than manufacturing, and the rise in casualised employment has been (proportionately) on par with the goods sector.

Given many services are delivered face-to-face, the commission says improved business practices can be harder to implement and the quality of a service can be difficult to establish before purchase.

Yet technology is finally enabling services to be provided remotely, accelerated by forced changes during the pandemic. For example, doctors are increasingly providing telehealth consulting, restaurants are joining online delivery platforms, and office workers are using more flexible working arrangements.

These are the sorts of innovations that increase choices for households and firms, driving improvements in both productivity and quality of life.

As every policy talk-shop galah has said, if Australia is to continue to enjoy high living standards and pay its way, it will have to lift its productivity game.

But the commission says a “cookie cutter” approach to policymaking is not necessarily appropriate for many service industries.

“Although some policy areas have economy-wide implications (such as industrial relations and taxation), reform of many service sector industries demands a more bespoke approach, requiring detailed knowledge of the industry’s structure and regulatory environment,” it says.

The commission’s challenge is to find the sweet spot between policy and politics.

No matter how much iron ore we ship or how often politicians tickle our patriotism about being a country “that makes things”, we earn our living from the services sector.