Plea for Australian help to quell brutal PNG fighting as Canberra and China struggle for influence

The governor of a remote Papua New Guinea province racked by tribal fighting has appealed for Australian help as the nation struggles to contain violence.

The governor of a remote Papua New Guinea province racked by tribal fighting has appealed for Australian help as the nation struggles to contain surging violence that has seen dead people dragged by four wheel-drives and a flood of automatic weapons into the country’s Highlands.

The Australian can reveal that multiple tribal conflicts have claimed the lives of an estimated 150 people this year, including two dozen lives in the past fortnight alone, and left thousands homeless.

The bloodshed in PNG’s Enga Province is threatening to further destabilise Australia’s nearest neighbour and biggest aid recipient, which is at the centre of an intense contest between Australia and China for regional influence.

The fighting comes as PNG faces a financial crisis and surging population growth that has strained the government’s ability to provide basic services, as Beijing looks to take advantage of any regional instability to further its own strategic interests.

Police have blamed politicians for fuelling the brutal violence, while local MPs, including Governor Sir Peter Ipatas, have accused police of failing to deal with the perpetrators.

At least three tribal fights are currently under way in the province, waged with high-powered military rifles, home-made guns and metre-long bush knives that leave victims with devastating wounds.

Grisly videos and images of the carnage are circulating on social media, including recent pictures of slain and naked fighters being towed by vines from a Toyota ute.

The International Committee of the Red Cross, which is on the ground in the province, said women and girls displaced by the fighting faced being “raped in really big numbers”.

Australia is alert to the issue, announcing $1.4bn in the May budget to support peace and security building across the Pacific but the Albanese government has not publicly advocated on what is seen by PNG as a highly sensitive matter.

PNG Prime Minister James Marape, an ally of Australia who has taken a wary approach to China, announced on Tuesday that those who engaged in tribal fighting would face life imprisonment under proposed new legislation aimed at ending the horrific violence.

The governor’s plea for Australian support comes just weeks after the Albanese government released its new foreign aid policy promising a whole-of-government effort to support Pacific partners to become “effective states.

Australia is on track to provide more than $600m worth of aid to PNG this year, on top of hundreds of millions in budget support loans.

Australia rapidly mobilised a peacekeeping force to send to Solomon Islands in 2021 after a request by Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare to quell rioting in the capital. Mr Sogavare has since signed a security pact with Beijing and Chinese police have been training Solomon Islands law enforcement officials.

There has been no such request for police help to Australia or any other country from Mr Marape.

PNG police commissioner David Manning has ordered his officers to use lethal force against armed tribesmen and mercenaries contracted by clans to fight on their behalf.

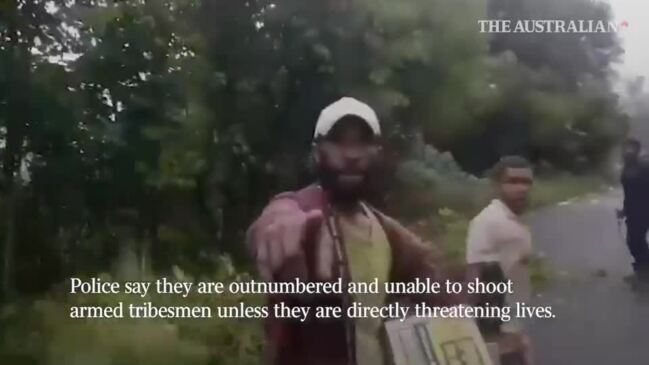

Enga’s provincial police commander, Superintendent George Kakas, said his officers were outgunned and legally unable to shoot fighters carrying weapons unless officers or civilians were in immediate danger.

The explosion in tribal violence is just the latest in PNG’s Highlands region, and comes as conflicts simmer in at least two other provinces – Hela and Southern Highlands.

Sir Peter, a “Grand Chief” of the PNG system who has served five terms, said the Royal Papua New Guinea Constabulary had shown “they are not able to effectively do their constitutional duty and that is to basically arrest criminals or offenders”.

“I have said many times that we do not have the capacity to fix this,” he told The Australian. “We need the government to ask the Australian government to give us some manpower so the police men and women in Australia can contribute to a contingent that would be sent to PNG to work alongside our policemen and women.”

Sir Peter said he wanted to see Australian police officers walking side by side in Enga with their local counterparts to prevent more violence, and to help PNG police to “develop the right culture to be a policeman or woman”.

“We need Australian police officers to help our (Central Intelligence Division), the prosecutors, and assist the provincial police commander in managing the province. There is a lot to be done.”

Another Engan leader, Kandep MP Don Polye, backed the call for Australian support, saying AFP officers were needed to train their PNG counterparts.

“Community policing is absent in PNG. In Kandeep for instance, I have I think four regular, properly trained policemen looking after 80,000 to 90,000 people in the electorate,” he said.

“We don’t want (AFP) doing operational stuff, but they could train police trainers, who could train police at the provincial level and the district level.”

The AFP currently has 32 sworn officers in PNG but none is specifically tasked with supporting efforts to tackle tribal violence.

They are constrained from carrying weapons or acting in frontline roles after a 2005 Supreme Court found they could not be granted legal immunities under PNG’s constitution.

Superintendent Kakas said there were three ongoing tribal fights in the province – all in Wapenamanda District – that had so far claimed about 150 lives.

He said battles following last year’s national election in three other districts – Kompiam-Ambum, Porgera and Laiagam – were now under control after a combined 200 deaths.

Superintendent Kakas said he had a force of 260 police across the province, backed by 120 soldiers, but they were unable to contain the violence.

The provincial police commander said each tribe had 10-20 guns, and 200-300 mercenaries with military-style rifles had flooded the province, charging PGK1000 a day ($430) for their services.

“Enga has a culture of tribal fights but now we have seen a switch from the normal tribal fights over woman and land. Recently it is because of politics getting in the way,” he said.

“And we see the trend where they are going from bows and arrows and spears … to high-powered factory-made firearms.”

Superintendent Kakas said the weapons were flowing into the country from Indonesia and Australia, traded for drugs, money and women.

“It involves well-to-do people; people with connections; businessmen; and politicians who are bringing those guns in to protect their own territory and tribal land,” he said.

The Australian is not suggesting any Engan MP is encouraging the conflict, only that the allegation has been made.

The International Committee of the Red Cross told The Australian it was monitoring 23 tribal conflicts in PNG this year, some of which were ongoing and some that had subsided.

“That we know of, about 150 people have died during this year in different parts of the Highlands due to tribal fighting, but it could be more,” the ICRC’s Lorena Martin Redondo said.

She said an estimated 5600 people had been forced from their homes by recent fighting, while up to 50,000 had been displaced across the Highlands this year.

“They lose their houses, which are easily burned; they lose their agriculture, their animals, and their livelihoods,” she said. “They also lose civilian infrastructure such as schools or health centres.”

She said women and girls were particularly vulnerable. “Sexual violence is very prevalent in PNG, especially in the Highlands. When it comes to tribal fighting … women are raped in really big numbers.

“So we support victims of sexual violence with psychosocial support and making sure they get the appropriate treatment they need in the first 72 hours after the rape has happened.”

The Enga violence is complicating the scheduled reopening of the province’s Porgera goldmine, which is part-owned by Canadian multinational Barrick and China’s Zijin Mining Group, and which has itself been blighted by years of alleged human rights abuses.

The mine, which contributed almost 10 per cent of PNG exports, has been closed for three years as the nation’s government renegotiated its lease to secure a 51 per cent stake in the venture.

Former Australian high commissioner to PNG Ian Kemish, who is currently an expert associate at ANU’s National Security College, said economic development was key to addressing the surging violence affecting the country.

“Historically there is a clear correlation between the state of the economy and law and order across PNG,” Mr Kemish said.

“We saw it in the 1990s when the Panguna mine, which was one of the country’s economic mainstays, was shut down.

“We do need to see next steps in a number of big resource projects, including the Total-led new LNG project.

“But PNG also needs to find a way of actually delivering on the huge potential it has in agriculture and fisheries.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout