Over-50s rebellion threatens to derail vaccination program

Effectiveness is a receding issue with the AstraZeneca shot, which has undoubtedly saved lives and prevented hospitalisations. A Scottish study of 1.1 million vaccine recipients showed that one shot of AZ or Pfizer-BNT was, respectively, 88 per cent and 91 per cent effective in preventing hospitalisation a month following vaccination. One dose of either vaccine appears to halve transmission based on a study of 365,447 households in Britain.

However, a looming resurgence driven by the B1.617.2 “Indian” variant in Britain has prompted authorities to shorten the AZ dosing interval from 12 to eight weeks. This is because a report showed that preventing symptomatic infection against B1.617.2 requires a full course of either AZ or Pfizer-BNT, which have an effectiveness against this variant of 60 per cent and 88 per cent respectively. Uncertainties remain around the effectiveness of the AZ shot against the South African variant, but with published real-world data looking good, why the reluctance?

A cognitive dissonance has arisen around messaging. How can a vaccine associated with a serious but rare side-effect that has resulted in its withdrawal or restriction in several countries, its deletion from the US arsenal and the EU’s 2022 portfolio also be extremely safe?

Historically, vaccines with serious side-effects have not persisted, especially when viable alternatives exist. The oral polio vaccine was dropped from our national schedule in 2005 due to a one-in-two-million risk of inducing polio in children. In Britain, the clotting disorder termed thrombosis thrombocytopaenia syndrome has a rate of 12.3 per million, but the AZ shot remains in use here because of limited options and/or expediency.

That TTS outcomes are apparently good in Australia is cold comfort to the 24 people who developed it. Treatment is experimental and non-trivial, ranging from immunoglobulin (donor antibodies), steroids, blood thinners and surgeries with long-term outcomes unknown. Unlike Germany and Norway, the details of our cases including management are a state secret, but should be released to educate the public and doctors.

This is especially relevant to ensuring good outcomes for the 30 per cent of Australians in regional and remote communities who are at real risk of being diagnosed late.

Utilitarianism, or defence of the “common good”, has not swayed many individuals. Why? Because patient autonomy and choice, imbued by lived experience and personal trauma, is sacrosanct. For example, a patient recovering from a paralysing stroke will not risk having another no matter what the experts say. Our policy for over-50s has uncoupled personal choice from action thanks to the somewhat opaque calculations of the Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation, which is balancing the risks of critical illness against TTS. That 50-59-year-olds have the highest burden of TTS, accounting for 26 per cent of the 309 British cases, demands review of our age threshold.

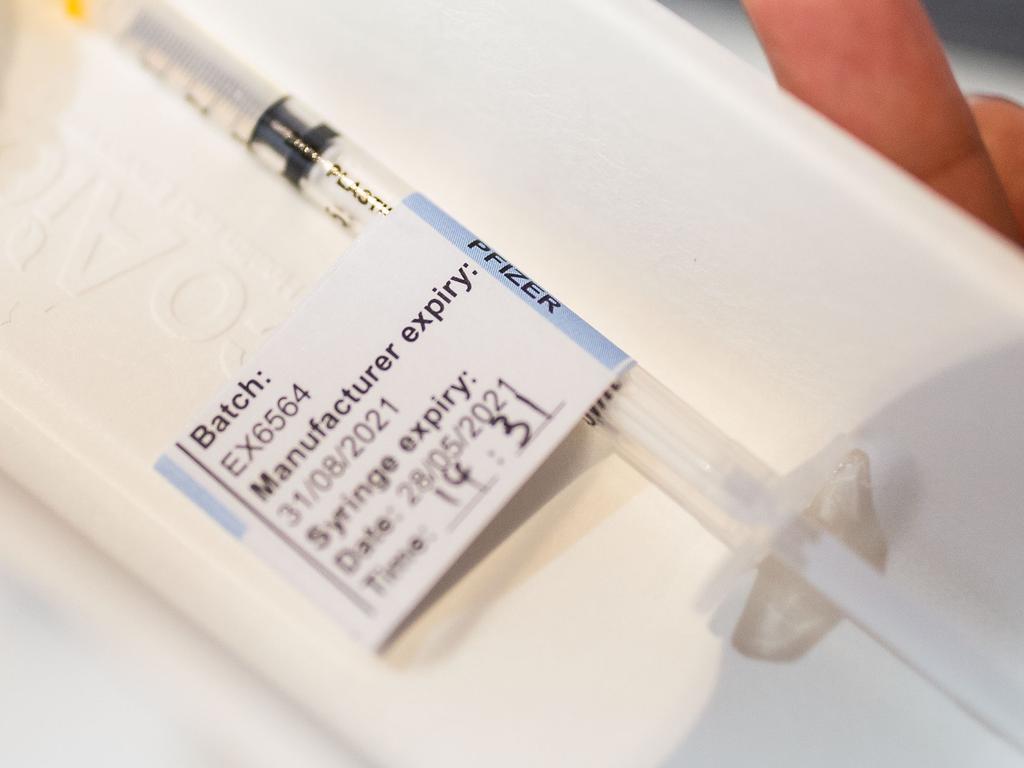

When the options are a good, but not best, vaccine versus no vaccine, then the choice smacks of coercion. Given their poor outcomes, it is imperative as many older Australians as possible are vaccinated pre-winter. Therefore, the age threshold should be dropped and Pfizer-BNT stock diverted to over-50s. This will provide faster and possibly more effective protection against symptomatic infection than AZ in the event of a B1.617.2-fuelled outbreak.

A susceptible population at risk of a variant-driven outbreak is the worst-case scenario, but it will not be a self-fulfilling prophecy if authorities Covid-proof our high-risk settings such as quarantine and hospitals. The real issue is the concerns surrounding the AZ shot risks spreading to the other vaccines or to the act of vaccination itself. This is not in anyone’s interest either now or into the future when we may have to bring people back for boosters.

Dr Michelle Ananda-Rajah is a general medicine and infectious diseases specialist in Melbourne.

Many Victorians are now rushing for vaccinations. However, this perception of risk may not be shared by Australians elsewhere. A standoff has erupted between authorities and a swath of over-50s reluctant to accept the vaccine offering. They have been denounced as being a drag on our economic recovery, of misunderstanding risk while holding out for alternatives, and of putting the entire community at risk. Peak outrage was reached with demands that refuseniks should pay for their hospital bills if they get Covid. There have been calls to jazz up our drab advertising campaign, incentivise vaccination with beers or link it to privileges such as domestic movement.