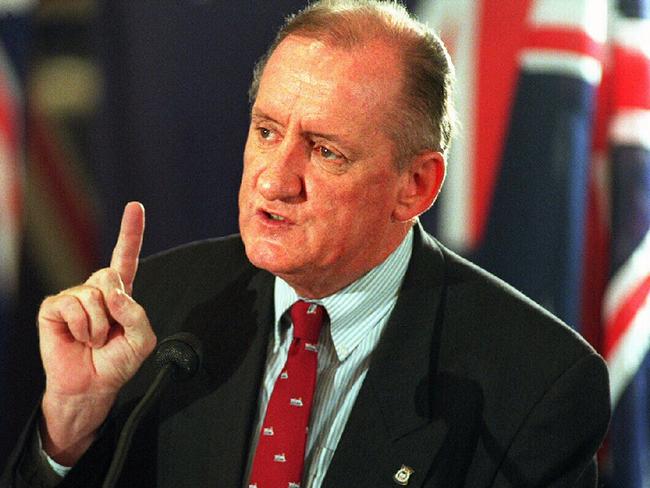

Obituary: Tim Fischer, 1946-2019

From unassuming conscript turned Vietnam War officer, to party leader. Tim Fischer never slowed.

Deputy Prime Minister 1996-1999. Born Lockhart, New South Wales, May 3, 1946. Died Albury, New South Wales, August 22, 2019, aged 73.

Tim Fischer was the most underrated politician of his era. He was the Boy from Boree Creek, the Man with the Hat, Two-minute Tim, the gangly tanglefoot at school, the unassuming conscript “Nasho” turned officer in the Vietnam War, the budding politician with a speech impediment, the devout Catholic in the wrong political party and the unassuming backbencher with a hidden, burning ambition.

MORE: Tim Fischer dies after battle with cancer

After politics he was an out-of-place farmer and steam-train enthusiast in the world of diplomacy who caused diplomats to cringe.

Yet, while he was a national leader derided for being a hayseed who sometimes said stupid things, the contradictions and misconceptions misled the critics, and Fischer’s opponents, into underestimating him.

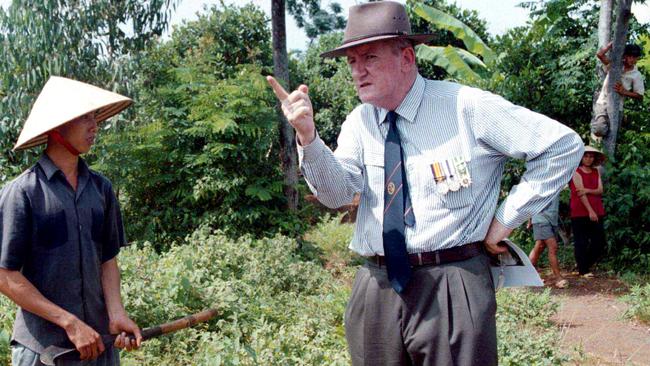

Timothy Andrew Fischer was born on May 3, 1946, at Lockhart in south-western NSW near the family home and farm at Boree Creek to Ralph Fischer and Barbara Van Cooth. After a slow start at Xavier College in Melbourne, he showed a gift for words, turned conscription for National Service into a life-changing experience as a prize-winning officer who served with distinction in Vietnam — where he was wounded and contracted malaria — and served a total 30 years in the NSW and federal parliaments.

Fischer was the first Catholic elected as a National NSW MP, he served as the party whip in NSW and as an Opposition frontbencher for nine years before being elected in the new federal seat of Farrer in the Riverina in 1984. He served in the House of Representatives for 17 years during which time he became the leader of the National Party (1990 to 1999) as well as the Minister for Trade and Deputy Prime Minister in the Howard Government from 1996 to 1999.

In an era of leadership of instability for all political parties Fischer was elected “unexpectedly” as National Party leader to take the place of Charles Blunt, who had been defeated in the 1990 election. It was a time of crisis for the junior Coalition partner and yet Fischer reshaped and revived the party and remained as leader until he chose to retire from that role and as Deputy Prime Minister in 1999, with the Nationals restored and significant political victories to his credit.

Former prime minister John Howard always acknowledged the key role Fischer and his deputy John Anderson played in passing Australia’s historic uniform national gun laws after the Port Arthur massacre in 1996.

Regarded by his senior Coalition colleagues as an intuitive politician, Fischer worked closely with Howard as prime minister and Peter Costello as treasurer. Fischer left Howard and Costello to handle the details of policy decisions, but was prepared to lead the way for Nationals’ policy changes, defying those who said he would not last.

Fischer also defied the political and media barbs directed at his bachelor status — he was 43 and single when he became leader — keeping his relationship with a younger Judy Brewer, also from a Victorian farming family and a National Party activist, private until he proposed to her in 1991. They married in 1992 and Fischer became a devoted father to two sons, Harrison and Dominic, although torn by the amount of travel he did as leader and Trade Minister.

While citing family reasons for wanting to retire — Harrison had autism — and do less travel and work, Fischer continued to defy expectations and commit himself to causes. He was, variously, an observer during the independence process for East Timor, chairman of Tourism Australia, Australia’s first full-time Ambassador to the Holy See at the Vatican in Rome and chairman of the Crawford Fund supporting international agricultural research and the world seed bank. In 2005 he was named in the Australia Day honours list as a Companion of the Order of Australia.

All this from a young farmer without a university education and with a pronounced lisp, which he could never entirely conquer (occasionally saying “fink” instead of think) who his critics said “wouldn’t last more than six months” as Nationals leader.

While not seen as brilliant at school or in the officers’ training course, Fischer always said the discipline and organisation he learnt during officer training were the reasons for his unassuming success and the substitute for a university education, an opportunity he turned down partly because he didn’t had no desire to avoid national service.

In fact, it was partly Fischer’s own guile and political intuition which led people to underrate him, to their own detriment and to his advantage. Fischer only lost one leadership ballot, the first ill-advised attempt at State level; he was elected six times to represent Farrer; and successfully managed a tricky Coalition partnership while keeping the rebellious Queensland Nationals under some control.

Fischer was also instrumental in drawing back disaffected Coalition supporters who had flocked to support Pauline Hanson’s One Nation party from the latter part of the 1990s. The Nationals had borne the brunt of rural backlash against the gun laws and Fischer, with Queensland colleague, Senator Ron Boswell, worked successfully to head off Hanson’s first attempt to win a Senate seat in Queensland.

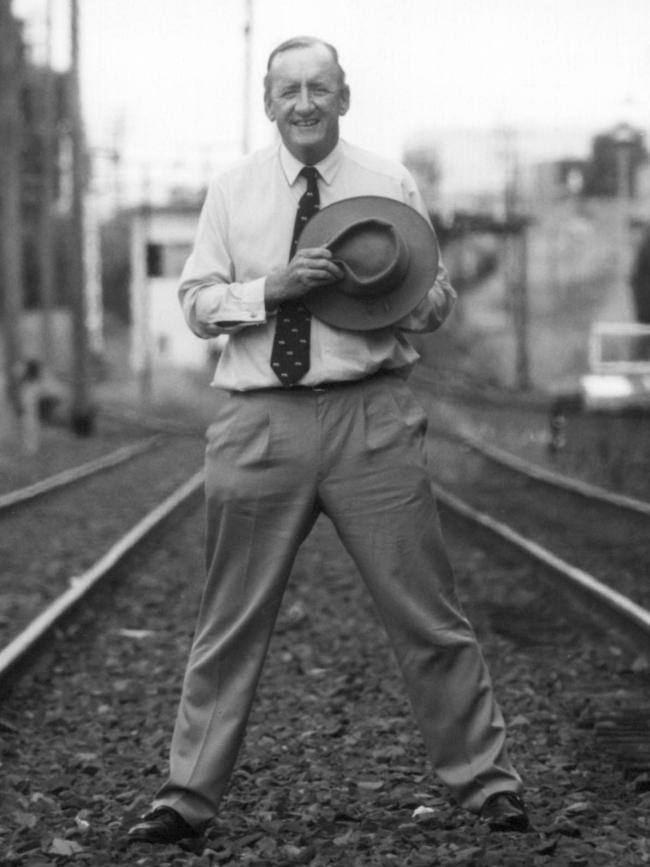

Fischer’s farmer’s hat became a trademark, a talking point and a badge of office so that he would stand out and be remembered. He would often recite tales of returning to a distant country on a trade mission and being instantly remembered because the locals recalled him thumping his hat down on the table as he came into negotiations — scandalising Foreign Affairs officials but leaving an indelible mark. The Man in the Hat had not always worn one as a politician and actually tried out a couple of Akubras before he consciously decided which suited his image best.

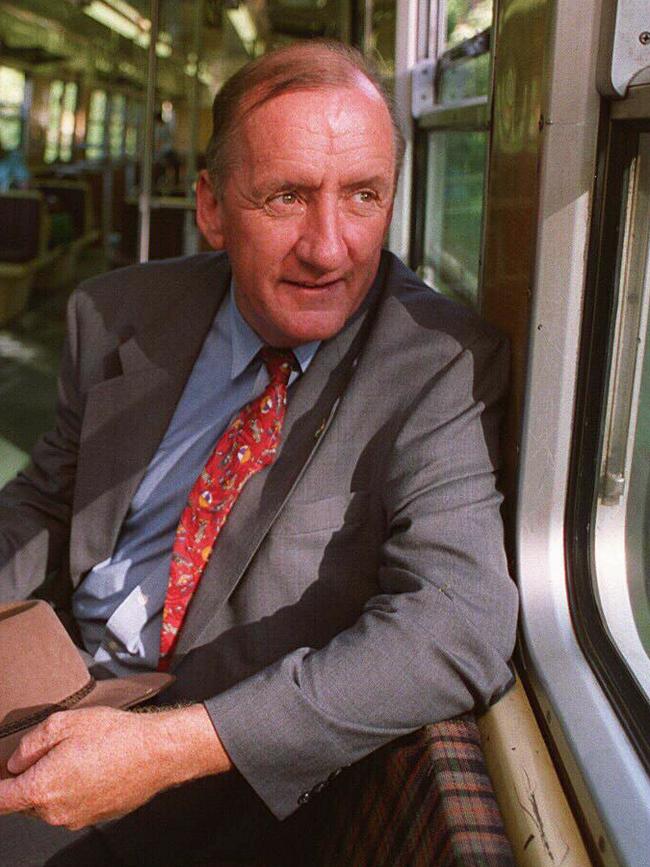

Fischer’s love of steam trains — one reason he developed a lifelong attachment to the isolated nation of Bhutan — and an encyclopaedic knowledge of rail systems earned him the nickname “Two-minute Tim” because he would appear outside the trains station in a small town when campaigning, make a short speech and move on. Once, when organising to meet me in Florence, Fischer suggested the train station and nominated a platform between the arrival and departure of a train from Rome which he had all in his head.

As a politician Fischer was renowned for adopting eccentric causes and sometimes appearing to look silly. When standing for his first election Fischer suggested a Boeing 747 testing facility should be located in the electorate and when in the NSW parliament he backed concerns about farmers in western NSW that lions may escape from the new Dubbo Western Plains Zoo and go feral, feeding on local livestock and hiding in the hills.

In 1994 during a drought Fischer called for the Captain Cook Fountain in Canberra’s Lake Burley Griffin’s — within sight of the Parliament House — to be turned off because it was “offensive” to those who hadn’t seen rain for two or three years. He was lambasted because it used recycled water, but for a week the focus shifted to the drought and the Nationals. For two minutes standing in front of a fountain for the television cameras Fischer got a week of publicity and attention. So, for all the appearance of being a hayseed, Fischer’s eccentricities were part of a highly successful political style which relied on under-promising, over-delivering and ensuring he was noticed.

Even the whistlestop appearances at country towns meant he could make a big impact on a local community and cover far more ground than his opponents. And, as for roving lions and recycled fountain water, Fischer was always prepared to be accused of being a fool or eccentric if the media turned its attention to the plight of farmers and he was seen as the vehicle for that change of focus to the bush and the natural Nationals’ constituency.

However, Fischer’s feel for publicity and for gaining the political advantage over his opponents never went beyond a gentlemanly approach: he did not attack individuals and earned the respect of all sides of politics. On the rare occasions when he himself was attacked on integrity issues — once over an alleged conflict of interest over shares and once in a scandalous claim about a fatal car accident in which he was seriously injured — Fischer’s personal standing ensured there was no real damage and no real pursuit in Parliament.

That Kevin Rudd appointed Fischer as the first Rome-based Ambassador to the Holy See to ensure the integrity and survival of the new diplomatic post was evidence of the cross-aisle support for Fischer. When the then Labor prime minister approached the retired Nationals’ leader and Fischer asked why Rudd didn’t want to “appoint one of your own” the reply was that no one would question Fischer’s appointment and it would ensure the viability of a new post.

When Fischer retired from politics he didn’t really slow down, he just redirected his energy and successful techniques with different aims, including helping international causes, agriculture and autism sufferers. Even cancer didn’t slow Fischer, who gave his all to everything that he believed in, regardless of whether others underrated or underestimated him.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout