Normal life must hinge on jabs, not herd immunity

The welcome arrival of vaccines should be a chance to spell out clearly when restrictions will be removed. On the government’s rollout plan, that should be by the end of April.

In December last year, about nine months after tough lockdowns were enacted, Italian births were almost 22 per cent lower than the same time a year earlier. The populations of Germany and Russia fell last year for the first time since 2011 and 2006 respectively, according to preliminary estimates, owing to a spike in deaths among the elderly and fewer births. Poland had the fewest births last year since 2005.

Uncertainty has long prompted families to put off having children. A decline in births has a more profound impact on a nation’s demography than a spike in deaths among the elderly. Australia’s fertility rate has fallen rapidly from almost two babies per woman in 2009 to 1.67 on average in 2019 (well below the rate of about 2.1 required to keep the population stable). The government slashed its fertility outlook for Australia for last year, pencilling in about 10,000 fewer babies than had been expected owing to the impact of COVID.

“Following this, fertility is assumed to resume its trend, which is driven by families having children later in life and having fewer children when they do,” the budget papers say, forecasting the fertility rate settling at 1.62 by 2030.

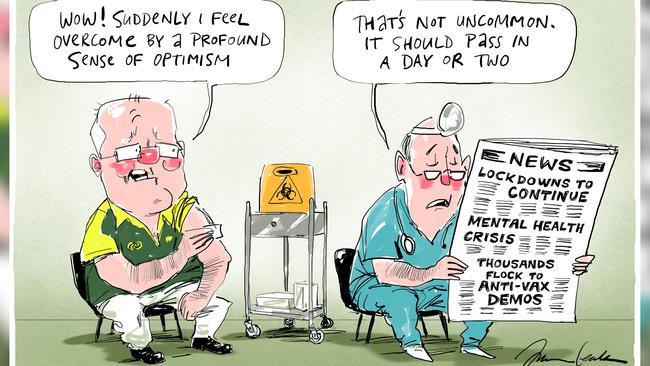

Whether the impact is permanent or temporary remains to be seen. Surveys by the Australian Bureau of Statistics reveal a rattled population. As recently as December last year almost 30 per cent of us still felt overwhelmed by COVID-19, while 31 per cent said we thought about COVID-19 “several times a day”.

In January almost a quarter of people aged 18 to 34 reported their health was “worse or much worse” than before pandemic restrictions began last year. None of this is conducive to having babies, not to mention the surge in unemployment has been concentrated among younger workers.

French economist Frederic Bastiat famously divided effects into those that are seen and those that are unseen. Falling fertility and the future social and economic costs of lockdowns that will emerge in years to come are good examples of unseen effects.

The welcome arrival of vaccines should be an opportunity to spell out clearly when restrictions will be removed. On the government’s vaccine rollout plan, that should be by the end of April — when frontline workers and vulnerable groups will have been vaccinated. That is, in six or so weeks we should open the border and lift other COVID restrictions.

Yet the government has been unacceptably vague about when the international border will reopen, refusing even to commit to October, when it hopes practically everyone will have been vaccinated. This leaves in limbo about 40,000 Australians abroad who are trying to get home, and international commerce indefinitely hamstrung. The lack of certainty stymies businesses’ employment and investment plans, especially in tourism and hospitality sectors.

A common justification for lockdowns last year, as it became clearer younger generations were at little risk, was the impossibility of protecting vulnerable groups without them. Now that those vulnerable groups can be protected there’s no need for the restrictions.

“Public health practices will stay in place until evidence shows that vaccination prevents transmission and herd immunity is achieved in Australia,” the federal Health Department says. That could be never, though.

Immunologist and University of Newcastle emeritus professor Robert Clancy has warned against seeing vaccines as a panacea rather than a tool. “The idea a vaccine would induce sterilising immunity and prevent community spread by creating herd immunity has become the dominant political and medical story … this was never a likely outcome,” he wrote last month.

Hinging the return to normality on achieving herd immunity, a poorly defined term in any case, is irresponsible. Vaccines are the key to normality, not herd immunity. Experts don’t know whether herd immunity is even possible for COVID-19, let alone likely. How long immunity lasts from the two approved vaccines and to what extent they stop transmission remain unknowns.

In nations where a high proportion of the population has been immunised, such as Israel, large numbers of new cases and deaths have persisted.

On Monday NSW Premier Gladys Berejiklian said until “the vast majority” of Australians had taken the vaccine, tough restrictions would remain. Even if the vaccines were perfect it would be a struggle to get everyone to take one. About three-quarters of Australians say they will take the vaccine, according to most surveys; but intention is a different concept to behaviour.

A government survey in 2003 found 18.6 per cent of Australians aged 40 to 64 had taken an influenza vaccine. You could assume the vaccination rate of younger adults would be lower still. For healthy young adults, influenza is at least as great a risk — albeit still a tiny one — as COVID-19.

While vaccines have been enthusiastically taken in countries badly affected by COVID, the urgency may be lower here. Only a sliver of Australians would know anyone who had contracted or who had been sick with COVID-19 during the pandemic.

If the government wants universal vaccination it might have to pay people, say $100. That would end up cheaper for taxpayers than spending further billions of dollars on COVID tests.

At least Scott Morrison’s initial plan to make the vaccine “as mandatory as possible” has been dropped for now. Last week Safe Work Australia said businesses would not be able to blacklist customers or staff who hadn’t been vaccinated.

“We will be living with this virus for at least six months, so social distancing measures to slow this virus down must be sustainable for at least that long,” the Prime Minister said in March last year. We’re only a month away from 12 months of restrictions of varying degrees.

BIS Oxford Economics analysts don’t expect pre-pandemic movements to return until the middle of 2023. That’s far longer than anyone predicted a year ago, when most experts were anticipating a much higher fatality rate.

When COVID-19 lockdowns began around the world last year, some joked of an imminent baby boom. In fact, a baby drought is emerging. In Europe, epicentre of the pandemic, birthrates appear to be collapsing.