Mum’s fears for asylum son tainted by time with Tamil Tigers

The mum of the man fighting to stay in Australia longs to see him but fears for his safety if he returns.

On the scuffed green walls of Nadeshalingam Murugappan’s family home in eastern Sri Lanka, a maxim written in English — a language none of the occupants can read — hangs above the television in a room full of anxious relatives.

It says: “Home is the place where, when you have to go there, they have to take you in.”

Whether “Nades” and his wife Kokilapathmapriya “Priya” Nadarasa end up back in the rural Sri Lankan district of Batticaloa they fled separately years ago — this time with two Australian-born daughters in tow — could be decided before the end of the month.

But in the living room of his mother’s home this week, any joy at the prospect of seeing the youngest of her seven children and, for the first time, her daughter-in-law and granddaughters is overshadowed by fear.

“They both have faced a lot of troubles here,” Nadeshalingam’s mother, Murugappan Alakamma, told The Australian. “We have spent so many years fearing he could be taken at any time or arrested. We are still worrying about that. Since he was in the LTTE, that threat will always be there for him because the government is scared they will regroup.

“We have spent our lives worrying about him. We don’t want to go back to that again.”

Sri Lanka is a country transformed in the decade since the 26-year civil war was drawn to a bloody close with the deaths of thousands of civilians caught in a grim last push by military forces to defeat the separatist Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE).

The military checkpoints, once every few hundred metres in the capital Colombo and every few kilometres on the highways leading to the former rebel-held north and east, have largely disappeared, notwithstanding a heightened security presence since the Easter Sunday terror attacks in which 258 people were killed.

Some refugees are returning as fear of the former security establishment — accused by the UN and Sri Lanka’s own investigative agencies of torture, disappearances, arbitrary detentions and extrajudicial killings — slowly eases, though there is anger at the government’s perceived failure to deliver the promised economic upswing.

There is also lingering resentment towards the Tamil Tigers who waged a bloody insurgency marked by suicide bombings and assassinations in pursuit of a separate state to free the ethnic Tamil minority from historical persecution by the Sinhalese Buddhist majority. And in recent months security officials have returned to the Murugappan home, this time on behalf of the Australian government seeking information on the family’s links with the LTTE.

The case

Nades, 42, Priya, 40, and their daughters Kopika, 4, and Tharunicaa, 2, face deportation after Australian immigration officials rejected their claim their lives could be endangered if they were returned because of links to Tamil separatists. Home Affairs Minister Peter Dutton has refused to exercise his discretion to let them stay, despite appeals from supporters in their former Queensland community of Biloela who argue they would make model Australian citizens.

Desperate for alternatives, the family says Priya and Nades recently asked Australian authorities to send them instead to India where Priya’s Indian father took the family to escape and where she and her daughters may have citizen rights. But they were told only Priya and the girls could go. Nadeshalingam would have to return to Sri Lanka.

Numerous appellate judgments have rejected Nadeshalingam’s claim that his time with the Tamil Tigers all but guarantees him legal troubles and potentially serious harassment on his return.

They point to the fact the war ended a decade ago, and that a technocrat government committed to normalising the country has been in power since January 2015.

That is all true. But at the village level in Batticaloa, palpable fears remain over the reach of the country’s security forces and imminent elections that could return to power the very government accused of human rights violations and mass civilian casualties in the last months of the war.

Last month President Maithripala Sirisena appointed Shavendra Silva, a general accused of presiding over the intentional shelling of hospitals, as the new army chief. The US embassy in Sri Lanka described the appointment as concerning. UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet called it a “worrying development”.

When security officials came calling three months ago, old instincts kicked in and the family told them Nades and Priya had no rebel links. “We were scared,” his elder sister Vijayalachumi told The Australian. “We didn’t know what would happen. They said they knew he was from the LTTE.”

Facing the prospect his family could be deported as early as next week, after a last-ditch Federal Court hearing on September 18, Nades has asked his relatives to hire a lawyer for his return and to seek character references for him from local officials.

His nephew Lambothavan Arulmanikkam says Nades sounded “very uncertain and sad” when they spoke last Thursday. “He is concerned he will be arrested immediately, about what he might have to spend on bail and to fight the legal battle he believes he will have to face,” he said. “He has no idea what will happen.”

A senior Sri Lankan military official told The Australian the family were “not of interest to authorities”. “We hardly have any records of them, even though they say they will be prosecuted,” he said. “They could come back here and settle down just like anyone else.”

But the Murugappan family is convinced Nades will face institutional discrimination, legal troubles and perhaps worse on his return, based on the past experiences of LTTE cadres at the hands of the former government.

Targeted by Tigers

Nades was on his way home from high school exams in then Tamil Tiger-held Batticaloa when he was caught up in one of the separatist guerrilla army’s roundups.

His four older brothers were in hiding, palmed out to relatives in safer towns to avoid conscription, but they had thought Nades was too small and too young to pique the interest of the LTTE. They were wrong. “There were five boys and they definitely wanted one of them but Nadeshalingam was only 17 at the time and we didn’t think they would take him,” his mother Alakamma recalled this week. “We were not sure where he was living, or if he was living at all.”

It would be a year before they could confirm he had been conscripted, and more than five years before they would see the “baby” of the family again. When they finally did he was a battle-scarred soldier, working in the LTTE intelligence unit. By 2002, under a ceasefire agreement, Nades returned to his village as an LTTE community discipline officer.

But as the ceasefire began to crumble under the newly elected Sinhalese nationalist government of Mahinda Rajapaksa and fighting resumed, he was forced back into hiding and eventually fled the country to work as a cleaner in a car showroom in Qatar.

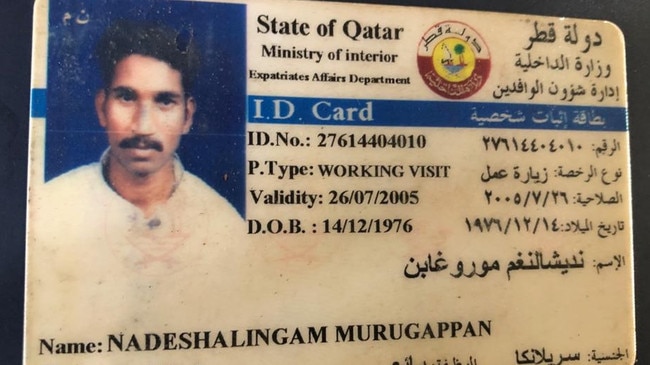

The family has photographs of Nades in Qatar, some from his days as an LTTE discipline officer, and many of his colourful wedding. There are none of him in his LTTE uniform. They say they burned those for their own safety. That is not unusual among families of former LTTE cadres who had reason to fear repercussions. But it hasn’t helped his asylum bid.

His siblings and mother describe the time after he first left for Qatar in 2005 as one of intimidation by security forces who would call at all hours looking for Nades. At least three times Nades returned to Sri Lanka; the first time spending weeks rotating between houses to evade security forces; the second — after an ill-fated trip to Kuwait — hiding out in Colombo until he could arrange to return to Qatar. It is those work trips, sanctioned by the Sri Lankan foreign ministry as recently as March 2011, that Australian authorities say disprove Nades’ claims of persecution because he had freedom to move in and out of the country. Chandrahasan, a Sri Lankan Tamil refugee advocate who runs the Organisation for Eelam Refugee Rehabilitation in India, said it was plausible Nades’ role as an LTTE intelligence officer might have only been revealed during interrogations in internment camps after the war. “It’s certainly possible, because the identities of those working in the LTTE intelligence wing were largely not known, and so he could have moved in and out,” he said.

The last return home

On his third re-entry in 2012, Nades returned to his village but eventually fled to Australia for fear he could join the ranks of LTTE soldiers and sympathisers disappeared during and after the war, sometimes after entering military camps where thousands were forced to check in weekly.

“It was never certain what would happen when he went inside that camp,” Alakamma said of the Sunday obligation that kept the family in a state of terror. “Every week he was scared. Sometimes I would go with him and wait out on the road. I never knew if he was going to come out.”

A few kilometres away from the Murugappan family home, Priya’s uncle Veerasingham Jayasingham says he too was forced to sign in every Sunday at the local army camp. The intimidation became so intolerable he fled the country in 1990 for the Maldives, returning only 13 years later.

He is clearly uncomfortable talking about the past, but lifts the hem of his sarong to show the scars from beatings doled out during the war by security forces. He says Priya’s family left for India a few years later, fearing the regular beatings her brothers also suffered at the hands of security forces could end in their disappearance.

“They left because they could not bear the harassment,” Veerasingham told The Australian on the broad veranda of their home. “People couldn’t live in this area then because so often they would be detained and beaten.”

But asked to verify Priya’s claim that one of her brothers was an LTTE cadre, he demurs. If he confirms Priya’s story he may put his own family at risk. If he denies it, he puts her in potential danger.

“Even today, telling the truth is dangerous. You never know what’s going to happen with this election. The one who killed innocent people during the war is running for election,” he said in reference to Gotabaya Rajapaksa, the feared former defence minister now running for president.

“There was a perception that all Tamils belonged to the LTTE or some other terrorist group. The risk still exists, even for those who were not in the mainstream LTTE but just supporting or aiding them.

For Nades, he insists, there will “definitely be consequences if they are returned”. “They might leave her (Priya) alone but they will cause trouble for him.”