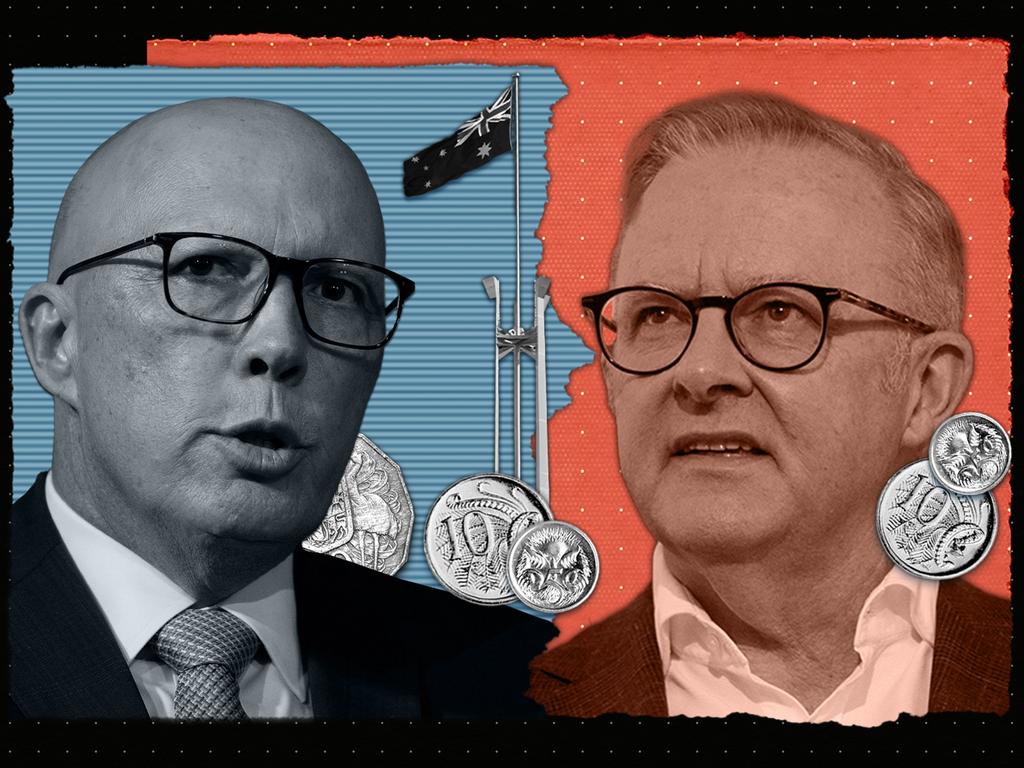

Peter Dutton describes the election as a sliding door moment for the nation. Anthony Albanese’s account calls for a contest between the past and the future.

Both leaders are right on this point. This election, more than many before it, has deeper consequences running beneath it.

The challenges for both the economy and the defence of the nation have rarely been more immediate in their need to be addressed.

As economist Chris Richardson puts it: “If society thinks elections are about a boot in the arse (for both sides) … it’s time for one.

“It worries me that there isn’t a sense of urgency about it.”

These are challenges for both Albanese and Dutton.

Contrary to the optimistic outlook presented by the Albanese government, everything we know about what the economy needs to be for Middle Australia is now at stake.

The sclerotic growth of government, over-regulation, big government, the power of unions and the worst of big business is throttling the economy. In turn, this is throttling the aspirations of many Australians.

At the same time, the geo-strategic outlook, the great power competition, is at its most perilous and delicate since the 1930s And just like the 1930s, Australia’s defence force is woefully ill-prepared to deal with potential challenges.

As a nation, we have been sleepwalking towards an idleness on the two foundational issues that underpin prosperity and security. This election presents a potential turning point.

At the heart of the economic question is the collapse of Australia’s standard of living, with weak prospects for a return to pre-2022 levels within the decade. We have rarely faced a situation where a weak economy has coalesced with such a weak fiscal position and significant debt.

The Howard government enjoyed a strong economy and healthy budgets. Hawke and Keating experienced both good and bad budgets and strong and weak economies but not at the same time, at least not heading into elections.

Today, the long-term structural decline and accumulated debt has coincided with a horribly weak economy.

From an economic perspective, this election becomes the most important for decades.

Geostrategically, it is longer.

Another three years of stagnating reform will see Australia run out of runway to get the economy back into the air.

The sclerosis gets baked in. Collapsing small businesses, shattered dreams of home ownership, and mortgage prison become entrenched.

Dutton claims to have a superior command of how to address them.

The Albanese government’s record isn’t good. Dutton’s assertion that the country can’t afford more of the same over the next three years is difficult to contest.

Yet the challenges are blind to ideology.

The key indicator is the collapse in living standards, which have fallen off a cliff over the past three years. This is an undeniable problem that Labor has refused to acknowledge.

But taken over a 10-year period, taking into account time served by the former Coalition government, the picture isn’t much better. Going back 10 years, Australia’s living standards have risen just 1.5 per cent over the decade. This compares to 22 per cent for the OECD. In other words, we are making 1/15th the progress of other rich nations in terms of living standards.

Without rising living standards, everything becomes harder. And it extends into every fabric of society, beyond just the economy.

Once envied around the world for our standard of living, Australia risks being entrenched at the bottom of the OECD pile.

Economists such as Richardson point to this problem in particular, which captures the broader problems in the management of the economy and public finances.

But his message is to both sides of the political aisle.

More of the same will consign Australia to mediocrity.

Using a raw measurement of spending, there is little difference over the medium term between both Labor and the Coalition. Of the $3 trillion going into the budget and the same coming out over the forward estimates, the difference amounts to around 1 per cent.

“More of the same is not a great recipe for Australia,” he says. “We don’t have a budget match fit for a dangerous and fractured world.”

Dutton’s position appeals to the two fundamental challenges but so far is limited in policy response.

The Albanese government speaks to its record in its first term.

Yet neither has offered an explicit pathway back to returning the budget to surplus.

Considering the challenges and risks that both leaders acknowledge lies ahead, this is insufficient.

Dutton’s approach, at least rhetorically, is less government, with private sector empowered to refuel the economy.

Albanese’s model in government so far has been an unashamed pivot to a greater role for government in just about every aspect of the economy. This is not a sustainable model.

Dutton’s solution has yet to be fully framed or articulated. And largely because the size of the job isn’t something that can be presented from opposition if he wants to win an election. There may not be too many political rewards for what needs to be done eventually.

But how long can Australia stay on the trajectory it is on, where living standards continue to decline compared to its peers? at At what point does the nation finally wake up?