Facing a war with inflation, battles with business, the spectre of recession and flagging support for the voice to parliament, Albanese now also faces a potential political scandal involving senior members of his government.

Having had an easy ride for the first 12 months in office, Albanese is now under pressure, with the road ahead riddled with potential political potholes.

The key to the Brittany Higgins text revelations is who among Albanese’s cabinet colleagues knew what and when. There are unresolved questions about what level of involvement members of the then Labor opposition had.

Albanese has expressed full confidence in Finance Minister Katy Gallagher.

Why this is potentially damaging for the Albanese government is clear. A key part in the politics of Labor’s successful characterisation of Scott Morrison was that he was out of touch with women.

When the Higgins rape allegations surfaced, in a strict political sense, it was weaponised as part of the broader campaign against the then prime minister.

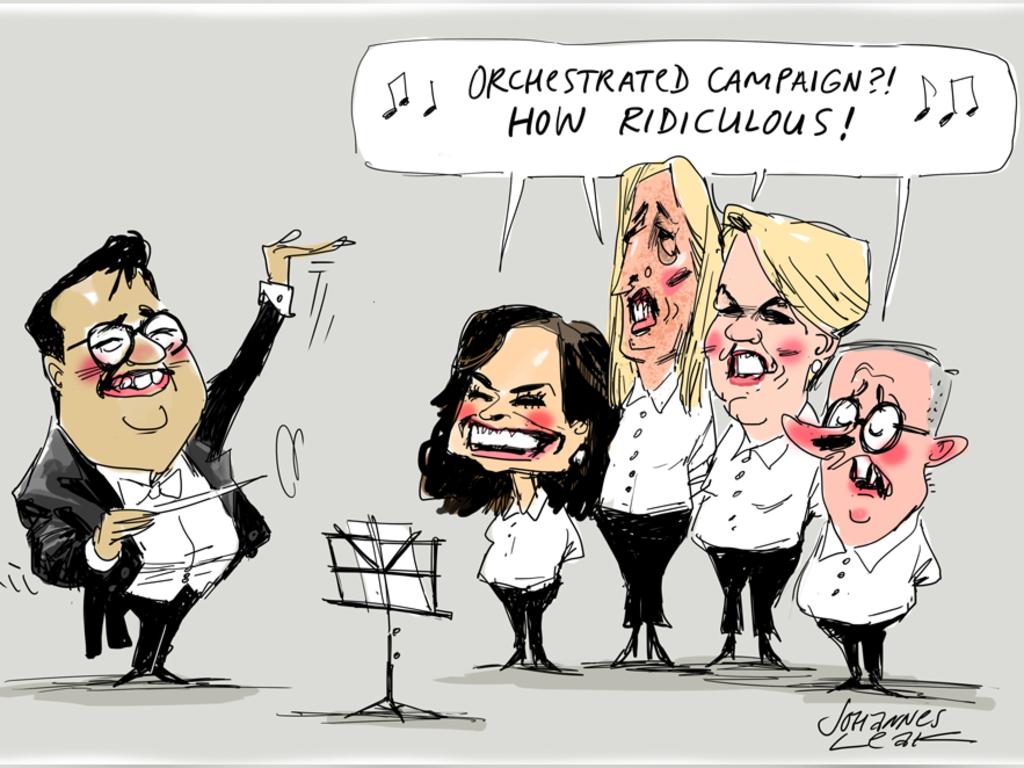

There was a deep suspicion among senior Coalition figures all the way through that period that there was active support being given to Higgins from political opponents of the government.

They were unable to substantiate any of it at the time.

The text revelations uncovered by The Australian this week have started to lift the lid on what was going on at a political level.

What is coming out now is an increasing body of evidence to suggest that there was a deep political dimension to the case that went beyond the legal and the personal tragedy of Higgins.

The political elements it appears involved senior people on the Labor side, some of whom are now ministers.

If the question is did Labor go too far in opposition, then the answer is probably yes.

And we are not yet at the end of it.

It is too early to start talking about referrals to an integrity commission that doesn’t yet exist.

This was a mistaken path for the opposition to go down yet. But it’s worth remembering that history has shown that the first people integrity commissions try to shoot are members of the government that created them.

As of this week, however, it presents another major distraction for Albanese, whose core focus after this week’s 12th rate rise in little over a year should be cost of living as the government’s first and second priorities.

The vexing domestic realities of being prime minister have landed squarely at Anthony Albanese’s feet this week after his return from overseas.