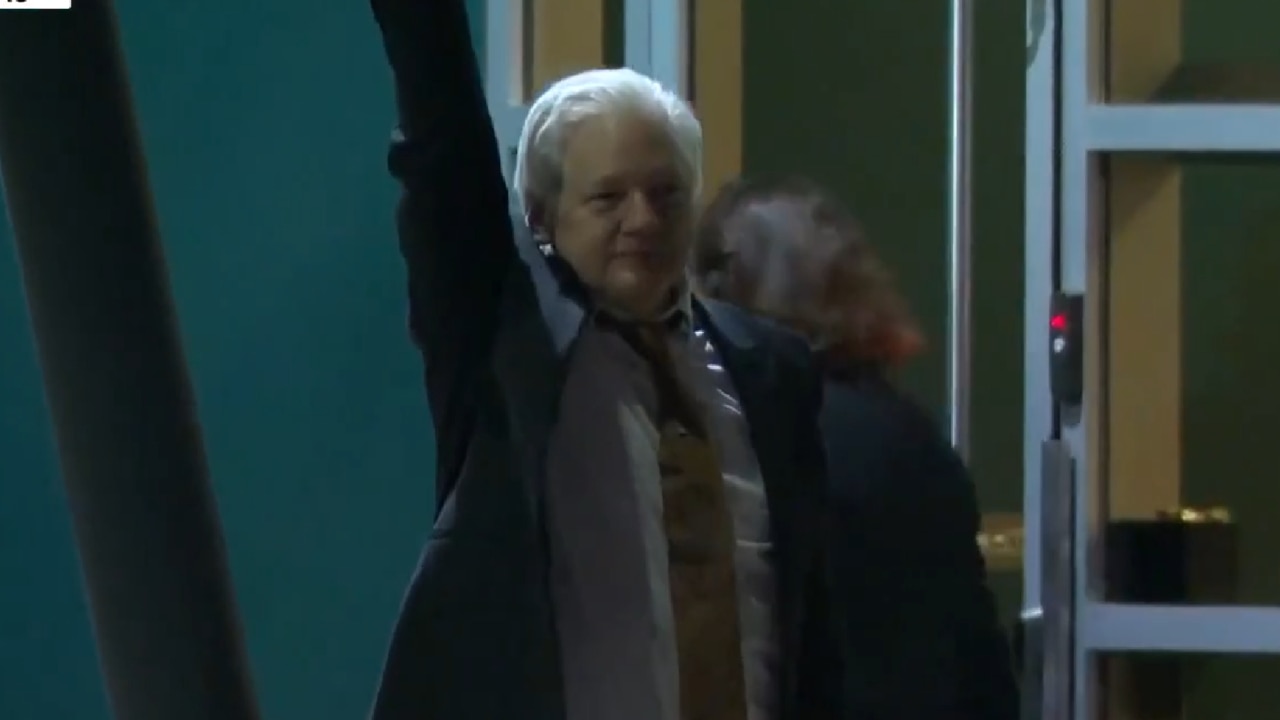

Julian Assange: Quiet diplomacy and Anthony Albanese’s push won out in the end

For all the grand diplomacy surrounding Julian Assange’s case, the crucial breakthrough in securing his freedom was getting his legal team to sit down and negotiate with the US Department of Justice.

For all the grand diplomacy surrounding Julian Assange’s case, the crucial breakthrough in securing his freedom was getting his legal team to sit down and negotiate with the US Department of Justice.

When Anthony Albanese came to office more than two years ago, Assange’s lawyers were locked in a battle to prevent their client’s extradition to the US. A plea deal wasn’t on the table, or being sought by Assange’s team.

As the WikiLeaks founder languished on remand in Britain’s Belmarsh prison, his overriding concern was his legal fight to avoid a life behind bars in an American jail. The Morrison government saw Assange as a hacker and a renegade and was content to allow his fate to be decided by the legal processes of Britain and the US. Labor saw him in a more positive light, and sensed growing public support for his case. Albanese said in opposition that Assange’s legal fight had gone on long enough.

After taking The Lodge, he intensified his public support, declaring the saga “needs to be brought to a close”. He cautioned that his government would work quietly and diplomatically on Assange’s behalf. The message was clear – Australia wanted its citizen released but it would not engage in counterproductive rhetoric.

The diplomatic and legal systems clicked into gear. They were now acting with the clear imprimatur of the Prime Minister. “This has been a project from day dot. It’s been a long haul,” a senior government official said.

Speaking anonymously due to international sensitivities, the official said Albanese had left no doubt in Washington or London regarding his views.

The first real sign of progress came in April, as Joe Biden hosted Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida at the White House. “President Biden, do you have a response to Australia’s request that you end Julian Assange’s prosecution?” a reporter shouted. Biden replied: “We’re considering it.”

The statement electrified Assange’s supporters, but the government knew securing political support for a resolution wasn’t enough. The US system’s separation of powers meant its Department of Justice needed to come to its own conclusions.

“It wasn’t as simple as me sitting down with President Biden or any other US elected representative and achieving this outcome,” Albanese said after Assange landed in Canberra. “This was always going to be something that required discussion, patiently, with the Department of Justice. The details of the plea deal were worked through over a period of time.”

He said arms-length negotiations were the only way a resolution could be achieved.

Albanese, Foreign Minister Penny Wong and Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus raised Assange’s case with their US and British counterparts at every opportunity and empowered their officials to do likewise.

Australia’s ambassador to the US, Kevin Rudd, threw himself into the task after arriving in Washington in March last year.

Australia’s high commissioner to the UK, Stephen Smith, was also instrumental, using consular visits with Assange and talks with his legal team to encourage them to seek a deal. Rudd’s and Smith’s roles were underscored by their presence with Assange in Saipan on Wednesday, when he faced US District Court judge Ramona Manglona, who was required to hear his guilty plea on a single count of conspiring to obtain and distribute classified information under the US Espionage Act.

He had previously faced 18 such charges, each carrying a potential jail term of 10 years.

Assange, who had initialled and signed the documents two days earlier, remained defiant. “I believe the First Amendment and the Espionage Act are in contradiction with each other but I accept it would be difficult to win such a case given all these circumstances,“ he told the court.

Judge Manglona endorsed the 23-page plea deal. “You’re able to walk out … as a free man,” she told Assange, who turns 53 on July 3. “Happy early birthday for you.”

The agreement bars Assange from travelling to the US, but his wife, Stella, has flagged he will seek a pardon.

In a lengthy statement on Wednesday, the Department of Justice emphasised the gravity of Assange’s guilty plea, and the fact he was “aware of the harm that dissemination of such national defence information would cause”.

Ultimately, the plea deal satisfied both parties – something the Albanese government had sought all along.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout