John Cain: Victoria’s longest serving Labor premier

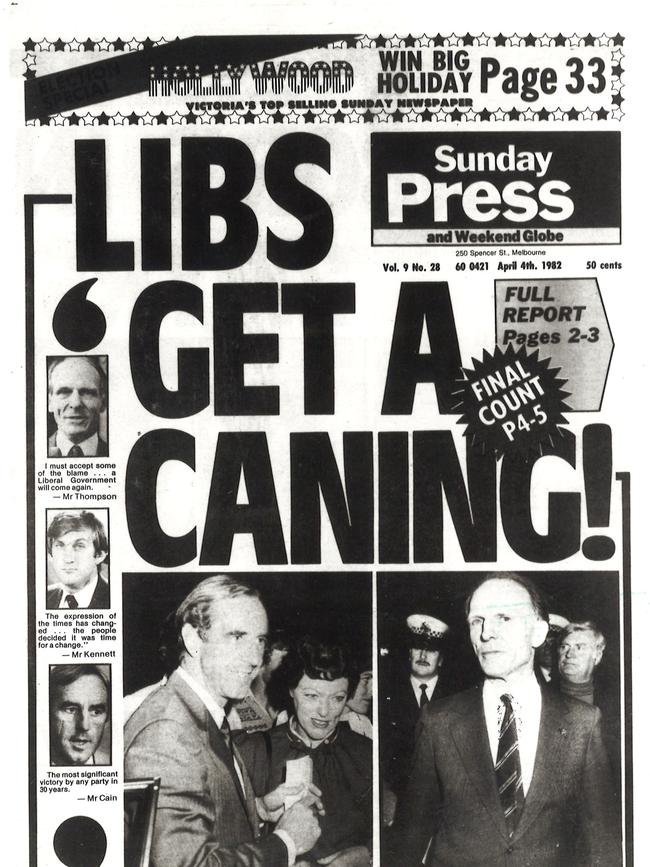

Victoria was traditionally the problem state for Labor. John Cain turned this around, winning the 1982 election after 27 years in the wilderness.

In 1942, a 13-year-old boy mounted a rostrum at his local high school and delivered an impassioned speech lauding the Labor Party and condemning conservative politics. Ultimately, John Cain junior’s spruiking for the re-election of his father as Victorian premier entered the archives of Cinesound newsreels.

Victoria was traditionally the problem state for Labor. In those bigoted years, militant Catholics and conservative Protestants viewed each other suspiciously across vast ideological chasms. The resulting impasse was death for electoral success. John Cain senior, himself a rural Catholic and sometime hawker and fruiterer, spent 38 years in the parliament while sitting on the government benches for only nine of those years. He had three stints as premier.

Then — as a result of the Cold War — came the threat of godless communism, which worried the Catholics more than the Protestants: after the Labor Party split of the mid-1950s many Catholics deserted.

In the 1960s a group of ALP members known as “the participants” sought to extend the appeal of the party to a wider, middle-class community. They included John Cain junior (his father had died in 1957), John Button, Race Matthews, Michael Duffy and Barry Jones. These future stars persuaded the rank and file to accept federal intervention and federal opposition leader Gough Whitlam as their personal saviour. This essential internal politicking paved the way for the election of federal Labor in 1972. Yet it was to be a further decade before the fruits of reform were enjoyed by the Victorian party: in 1982 John Cain led state Labor to victory after 27 years in the political wilderness.

Although parallels charting the self-destruction of these reformist governments are inevitable, Cain, unlike Whitlam, suffered opprobrium, and sometimes calumny, for the rest of his life.

John Cain’s mother Dorothea (nee Grindrod) was a middle-class business woman who owned dress shops. Cain first attended local primary schools and Northcote High. He spent a short and unhappy period at Geelong Grammar before enrolling as a boarder at Scotch College.

At 17 he joined the Labor Party. He studied law at the University of Melbourne and was admitted as a barrister and solicitor in 1954. He was articled to Jack Galbally, QC, for three years before establishing his own firm in Preston. In 1955 he married Nancye Williams, daughter of a federal public servant. It was a love match for life and the couple had three children.

Family succession

After his father died in 1957, while still a parliamentarian, Cain, now 26, sought preselection for his father’s seat but lost to a lifelong adversary, Frank Wilkes. Curiously, for one whose political ambition was established as a child, Cain then waited two decades before making a second run for parliament. Possibly the situation seemed hopeless with Henry Bolte and the Liberals winning six consecutive elections. Perhaps wisely he curbed his aspirations for the time being and dedicated himself to intra-party reform through association with the participants.

Cain rose through Labor ranks to become vice-chairman of the Victorian ALP in 1973. In addition he worked for reform within the legal profession. He was a member of the Law Institute between 1967 and 1976 and its president for two years and a member of the Australian Law Reform Commission from 1975.

Cain was 47 when, in March 1976, he won the seat of Bundoora. His capacity as a leader was mooted from the very beginning. He became a member of the parliamentary executive in 1977 and for six years was shadow minister for a variety of portfolios.

When leader of the opposition, Clyde Holding, stepped down in 1977 (after, what became known as his hat-trick of three electoral defeats) Cain presented himself for the top job.

Once again he was defeated by Wilkes. His ascendancy had been opposed by dyed-in-the-wool opposition members known derisively as “the shellbacks”. He bided his time until 1980 when he produced a comprehensive report damning the inefficiencies of the Wilkes shadow cabinet.

The new leader

On September 8, 1981, after a bloodless coup (lasting, it was said, four minutes) Cain replaced Wilkes as parliamentary leader. The 45-person caucus had voted unanimously. At a subsequent media conference in the Windsor Hotel, and with his adversary seated meekly by his side, Cain delivered a powerful speech described by one political commentator as “brimming with aggression, confidence and euphoria”. To excoriate a conservative government while retaining confidence in imminent victory was something of a novelty for Labor, and Cain relished his new-found power.

Nine months prior to the election, a weary Liberal premier, Rupert Hamer, resigned in favour of the colourless Lindsay Thompson. Cain hammered his contention that the level of waste and mismanagement of the state had reached grotesque proportions. Labor’s case was strengthened by an investigation suggesting corruption in numerous public water bodies.

Poll triumph

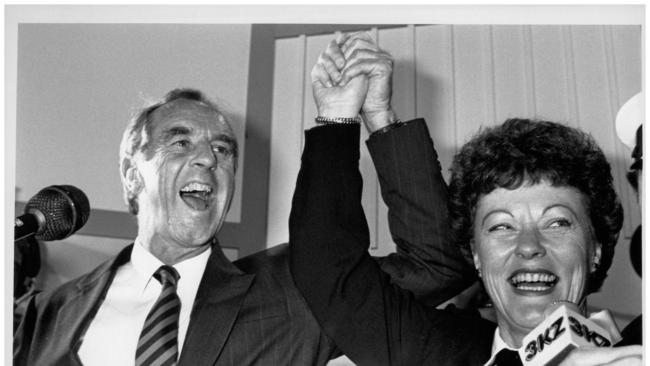

Cain and his team won a handsome victory in April 1982. The economy was sick and the state in debt. Additional problems were the moderation of union influence, the stabilisation of party factions, and the obstructions of the upper house. Cain achieved a modicum of success with the first two but major reform of the Legislative Council awaited the election of the second Bracks government two decades later.

Six weeks prior to Cain’s victory, Thomson had appointed a retired naval commander and viticulturist, Brian Murray, to the office of state governor. Just seven years after governor-general John Kerr’s dismissal of the Whitlam government, Murray made threats to the fledgling premier.

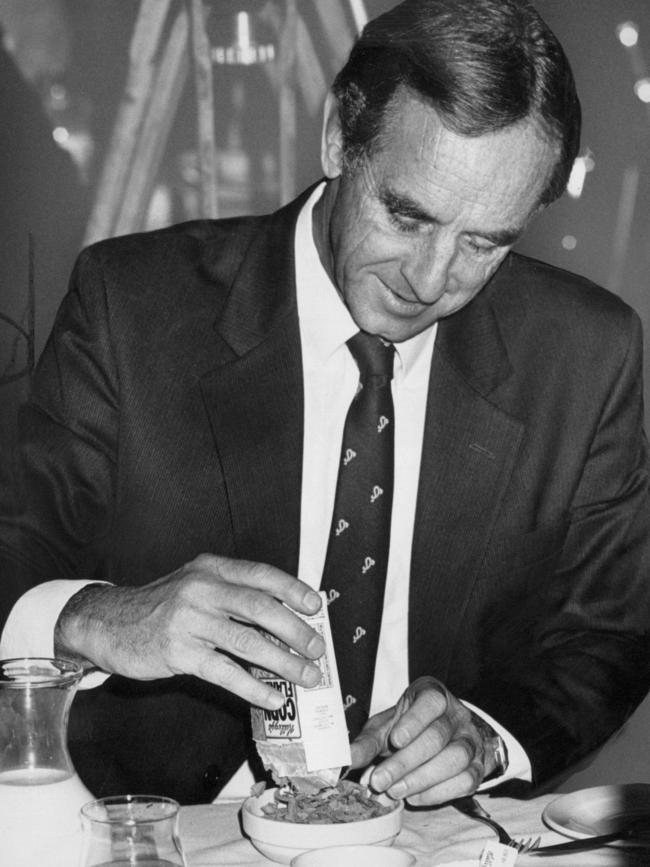

Cain bided his time for some three years until sufficient reason emerged to justify sacking the governor. In the meantime, the vice-regal household was grander, it was said, than Buckingham Palace. This was not to the taste of a premier who liked nothing better than a bowl of Weeties.

Cain instituted major social reform. It could be said that he presided over four good years out of his eight as premier. He created an independent director of public prosecution. His government reshaped Victoria in such areas as urban planning (notably Southbank) and the environment, industrial relations and workers’ compensation, mental health, law reform and parliamentary procedure. It liberalised liquor laws, supported the arts and helped transform the Spring Racing Carnival into an international event. It introduced nude beaches and legalised prostitution. All this from a premier who presented a dour, protestant, image. Cain led Labor to victory again in 1985.

Perhaps the seeds for Cain’s destruction were sown in his greatest triumph — the successful revival of the ailing Portland Alcoa company. “We unashamedly adopt an initiating role in seeking to change the structure of the Victorian economy to one more suited to the rigours of international competition rather than relying on market forces alone to generate the change,” Cain said.

He gambled that international demand for alumina, then stagnant, would recover. The $1050 million smelter opened in 1987 — then the world market picked up — and Alcoa became one of Australia’s biggest export earners. Flushed with Keynesian fervour, Cain established the Victorian Economic Development Council (VEDC).

On its recommendation, State Bank Victoria and its subsidiary Tricontinental, poured billions of dollars into the economy. Most of the recipient companies crashed. One merchant banker described the VEDC as “a last resort for desperados, and con men”. Members of the commission were said to be without experience in business or banking. It was alleged that it gave money to illicit drug manufacturers. A Malaysian princess absconded clutching her take of a million dollars. Tricontinental finally wrote off more than $1.3 billion.

In 1988 Cain called an election and won it narrowly, but during this third term of office came the final blow, with the collapse of the Farrow family’s building society, Pyramid, which lost more than $1bn.

It was the beginning of the end for Cain. A thousand demonstrators protested on the steps of Parliament House. Hundreds massed outside his home. In August 1990 he resigned, and Joan Kirner became premier. He resigned from the parliament in 1992, the year in which Jeff Kennett led the Liberal party back into power. Cain had led Victoria’s longest serving Labor government crushed by the Liberals.

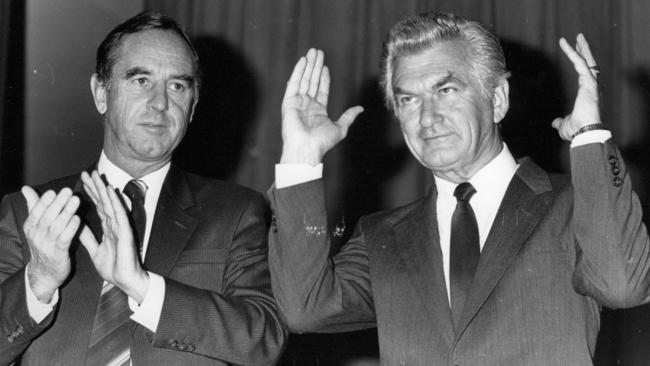

In 1995, he published John Cain’s Years, an account that blamed the “destructive” fiscal policies of prime minister Bob Hawke and his treasurer Paul Keating. He expressed bitterness at the public “betrayals” of leftist senator Kim Carr and Labor Unity state minister, David White. In the final analysis he was defeated, he maintained, by the misuse of power inherent in Labor Party factions.

History may well be generous to his memory. Political scientist Peter Botsman believes “the Cain government will prove to be one of the most outstanding in Victorian and Labor history”. After retiring from politics he became a professorial fellow at University of Melbourne, lecturer in politics and as a researcher and commentator on public policy. He has published three books and was chair of the State Library. He was awarded the National Medal in 1997 and the Centenary Medal in 2001.

Cain is survived by his wife Nancye Cain and children Joanne Crothers, John Cain and James Cain.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout