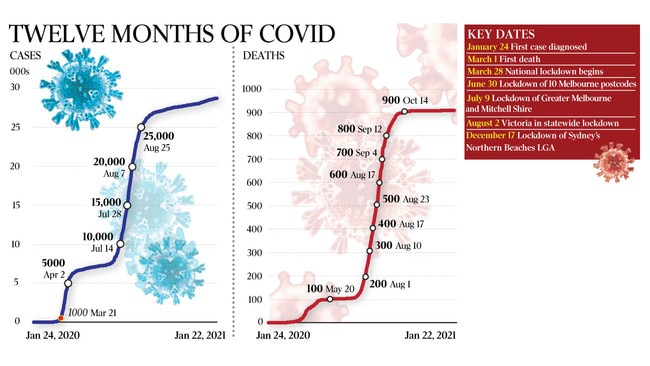

How the coronavirus pandemic unfolded in Australia from the first case on January 24

When Rhonda Stuart clocked on at Monash Medical Centre on January 24 last year, she never expected to be treating Australia’s first coronavirus patient.

When Rhonda Stuart clocked on at Monash Medical Centre on January 24 last year, she was ready for the usual shenanigans that Fridays tend to bring to hospitals, but not what this one held in store.

“Things always go a bit crazy on a Friday afternoon,” says Professor Stuart, an infectious diseases specialist. “And that’s what happened.”

About 9.30am, a man in his late 50s presented to the emergency department with flu-like symptoms, complaining that he was having trouble breathing.

It could have been a run-of-the-mill presentation for one of Melbourne’s busiest hospitals except for one key fact — the patient had recently flown in from Wuhan, China, where a new variant of coronavirus had emerged weeks earlier, putting health authorities around the world on alert.

“We found out that he was positive (for the coronavirus). And the next day we came in and realised that we had the first case,” Professor Stuart says.

The next day, federal Health Minister Greg Hunt revealed Australia’s first COVID-19 infection.

Despite attempts by Australian Border Force to isolate symptomatic international travellers on arrival, the virus quickly leaked into the community. Within a month, 24 cases had been reported. A month after that, when Scott Morrison announced a nationwide hotel quarantine program for international arrivals, the number had ballooned to 3162.

The Australian National University’s medical school infectious diseases professor Peter Collignon initially thought the virus could be contained in China but by the end of March he was proved mistaken.

“When I first heard about it, I thought we don’t have a problem because (it) was being presented as a Chinese — or what was coming out in the media — as only being a problem in wet markets where there was animal-to-people transmission,” the Canberra-based professor recalls.

“But February, it changed because (COVID-19) was found in other places and animals weren’t involved at all — it was just human-to-human and there was a reasonable amount of transmission occurring.

“It was the Diamond Princess (cruise ship) in Japan that really confirmed how readily it could spread in enclosed, indoor environments and many people could be asymptomatic and spread it.”

From the beginning, it was clear the virus was particularly dangerous for the elderly and people with chronic illnesses, with daily case tallies prejudiced towards those aged 70-plus.

The first Australian to die from COVID-19 was retired travel agent James Kwan, a 78-year-old man from Perth who had contracted the infection onboard the Diamond Princess cruise ship in Japan. His death was confirmed on March 1.

According to Australian Medical Association president Omar Khorshid, the virus gets into a patient’s cells, sparking an immune response that places significant stress on the body.

“In the case of this virus, it’s actually the immune response that’s been responsible for the lung disease that comes on a bit later,” Dr Khorshid says.

“People get ill and then sometimes they get a little bit better … and then bang! The lungs get full of flu, they get stiff and they can’t transfer oxygen properly.

“That’s your immune response. It’s your body trying to clear the virus, and that’s why from early on they were looking at steroids which modify the body’s immune response. So the reason (the virus kills) elderly people and people living with chronic diseases … is because they have fewer reserves, less capacity to cope with the stress of the viral infection and the immune response.”

It was the NSW Ruby Princess debacle that rammed home just how virulent this virus could be.

When the cruise ship docked in Sydney Harbour on March 19, there were concerns the 2700 passengers aboard could be carrying COVID-19. Nonetheless, they were allowed to disembark — and the disastrous infection control breach saw the virus spread throughout the country.

A Ruby Princess passenger presented to the North West Regional Hospital in Tasmania on March 20, followed by another six days later. With the infectivity of the virus yet to be fully appreciated, it quickly spread among staff members before ballooning to 138 cases, 80 of which were staff.

The outbreak prompted Tasmanian Premier Peter Gutwein to call in the Australian Defence Force. Eleven people died, nine of whom were patients and one aged care resident.

In the end, more than 660 Ruby Princess passengers contracted COVID-19, of which 28 lost their lives.

Melbourne-based emergency doctor Yiannis Efstathiadis still isn’t sure how he contracted the virus but thinks it was likely from a patient he treated at the Northern Hospital in late July. He experienced fevers, headaches and joint pain but did not experience a loss of taste or smell — a common symptom of the virus.

“It all really hit when I was on the ward and they came in and took some numbers, like heart rate and oxygen levels, and I could see them out of the corner of my eye that they weren’t doing too well,” he said.

As a result of a second-wave outbreak that bled out of hotel quarantine, Victoria accounted for 820 of Australia’s 909 deaths. Starting off at the Rydges on Swanston and the Stamford Plaza, the virus made its way into aged-care facilities across the state by way of a casualised workforce, where it preyed upon society’s most vulnerable people.

One of the worst hit was St Basil’s Home for the Aged in Melbourne’s Fawkner. Of the 94 residents who contracted the virus, 45 died. The home became host to heartbreaking scenes as Victorian health officials ordered the facility’s workers into quarantine, and the federal government sent in private contractor Aspen Medical to oversee the operation.

There were reports of St Basil’s elderly residents being left unfed and unmedicated as their children tried desperately to find out the fate of their loved-ones, many of whom did not speak English and suffered from dementia.

Klery Loutas’s mother Filia Xynidakis, 77, died in hospital on August 15, after dehydration accelerated her dementia. Months on and Ms Loutas wants the state and federal governments to take a close look at what happened in the aged-care sector and be accountable for the horror that unfolded.

“We are who we are because of our heritage and our loved ones who raised us and installed values and beliefs in us,” she says.

“I think our society is based on the teachings of our elders, and they deserved so much more, so much more than what they got.”

The profile of Victoria’s Chief Health Officer Brett Sutton has risen exponentially over the past 12 months — his face broadcast into the homes of Victorians daily as he provided updates on the spread of the virus. His task — detailing new cases and numbers of deaths — was a grim one.

Dr Sutton believes that Victorians showed extraordinary tenacity in defeating the second wave.

“I reflect on a year with immense pride that Victorians looked over a cliff edge of the kind of catastrophic outcomes that are playing out in the northern hemisphere and achieved the incredible situation we have today,” Dr Sutton says. “That took unbelievable perseverance and trust.”

The nation has now gone five days without a new case of community transmission, sparking some optimism that a pre-Christmas outbreak has been contained. State borders are reopening and remaining restrictions are being eased. Schools are preparing to kick off the new year by losing many of the limitations that were put in place last year.

But as many of the 27,800-odd people across the nation who have contracted and recovered from the virus will attest, the affects can linger. Joe Tannous of Sydney fell ill in March last year. It was after he tested positive that he became increasingly ill.

“The second week was definitely far worse than the first week,” recalls the otherwise fit and healthy 50-year-old.

“I was a lot more unable to speak without coughing and then towards the end of the second week, loss of breath … the fever was really hot to a point where I was using ice blocks to cool down.”

Mr Tannous was hospitalised on March 21, after which he was intubated and placed into a coma — a highly invasive procedure than many people do not survive.

Mr Tannous was one of the lucky ones in that he has recovered with no long-term damage to his vital organs. But anxiety around his health continues, exacerbated by headaches, shortness of breath and fatigue, especially when he exercises. He worries about what it means and whether he is going to die. “I don’t feel like the Joe Tannous that was pre-COVID,” he says.

Mike Catton, who heads up the Victorian Infectious Diseases Reference Laboratory at the Doherty Institute, says there’s a lot about COVID-19 that is still unknown.

Although he is excited that vaccines have been developed relatively quickly, he believes that Australians will be living with the virus for some time.

“It’s going to be very hard to snuff this thing out,” he says, “but I think the impacts will diminish with the vaccine as we move to coexist with this illness.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout