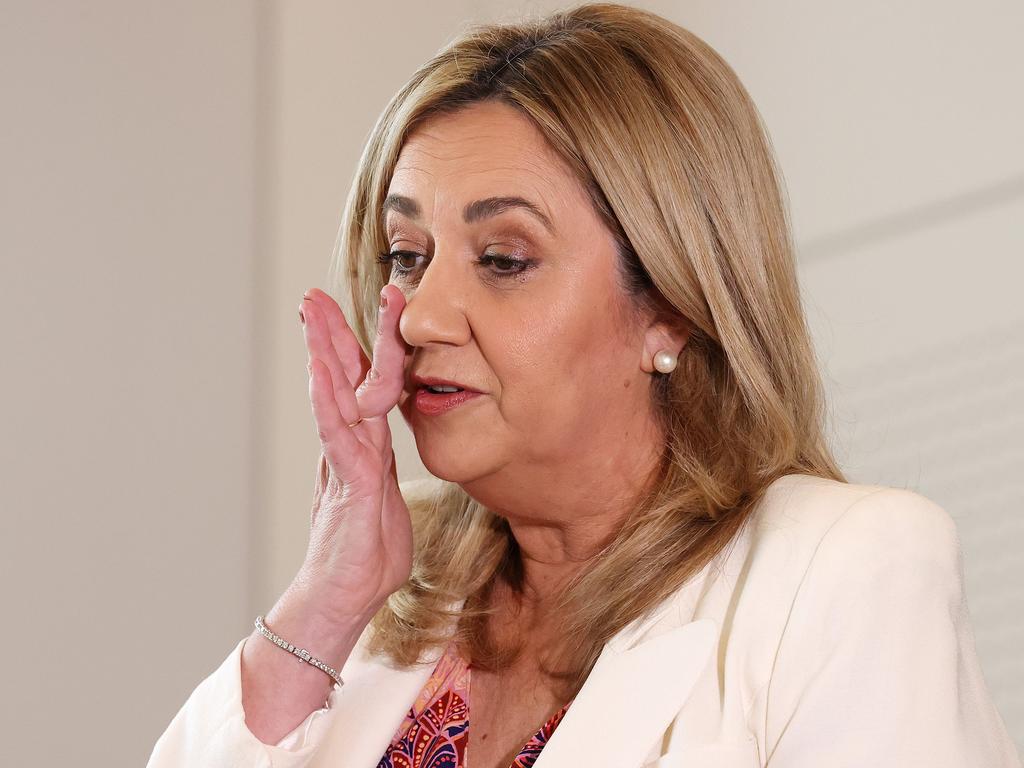

How Annastacia Palaszczuk hastened slowly to the end

Queensland’s 39th Premier went while she still had the choice. But make no mistake: she didn’t want to go.

Annastacia Palaszczuk ended her long, electorally successful but patently untenable premiership on her own terms, which is no small achievement. She went while she still had the choice.

As ever, there was a combination of humility and imperiousness to her actions, the paradox of her three state election victories in Queensland and longevity as Labor leader.

But make no mistake: she didn’t want to go. This was not a veteran leader who had run out of puff, who professed to lack the will or physical ability to soldier on. Palaszczuk was put on notice by the only people capable of getting through to her – the bosses of the industrial left and Queensland Council of Unions, the faceless power behind her throne.

The unrest inside the labour movement had been building for months, as successive polls showed Palaszczuk’s Midas touch with voters had lost its shine, with her personal popularity diving and Labor facing defeat at next October’s state election.

And it was coming to a head.

QCU general secretary Jacqueline King – who, at a rally last week, publicly admitted to disquiet among unions about Palaszczuk’s leadership – set out a confronting agenda for the regular quarterly meeting between union chiefs and cabinet ministers this coming Wednesday, a little-known feature of the governance structure under Palaszczuk.

According to several sources, King warned the Premier’s office of the intention to raise “big ticket” concerns such as cost-of-living pressures, and that the unions wanted to know what Palaszczuk and the government had planned to kick-off the election year.

“It wasn’t going to be a normal meeting, it wasn’t going to be nice,’’ one source said. “There has been a shift among the left unions, a widening belief that the government needed a reset to give Labor any chance of winning.

“Palaszczuk was facing criticism from all fronts and couldn’t get anyone to back her up. Knowing that there was going to be more coming at her … I think that in the past few days she woke up, smelt the coffee and knew she had to go.’’

Over the past month, United Workers Union national political director Gary Bullock, the king of the Left who sits on the ALP national executive and commands the allegiance of 34 of the 52 Labor MPs in state parliament, is believed to have had critical conversations with Palaszczuk along with state ALP president John Battams.

Their message was increasingly forcefully put, according to sources briefed on the discussions with the Premier. She should “consider her future” and it was in the best interests of the party, the government and the state that this happened before state parliament came back from the summer break next February.

Bullock rarely talks to journalists, and didn’t respond to calls from The Australian; Battams also likes to stay out of the limelight, but denied on Sunday an ultimatum had been issued to Palaszczuk last Wednesday.

Asked about well-placed suggestions he had spoken to her in the past week about considering her options, Battams said: “I don’t comment on any conversations with the Premier.’’ He then hung up. The union leaders’ intervention burst the bubble of delusion for Palaszczuk that she might muddle through to the state election.

Some major milestones beckoned to propel her further up the slippery pole of Queensland’s political greats. On May 10, she was to pass the nine years and 85 days Peter Beattie spent as Labor premier from 1998 to 2007.

Were she to win a fourth term and serve it out, Palaszczuk would go past another party legend, William Forgan Smith, and eclipse Country Party stalwart Frank Nicklin as the state’s second longest serving premier. Only Joh Bjelke-Petersen – with his record 19 years in office – would be in front of her.

Palaszczuk, 54, had devoted most of her adult life to Labor politics, taking the well-trodden path from apparatchik to a seat in parliament, which her father, Henry, a minister under Beattie, bequeathed to her on his retirement in 2006.

She was a mid-ranked but far from outstanding minister in Anna Bligh’s government by the time voters lowered the boom in 2012, reducing Labor to a rump of only seven MPs. Palaszczuk took on what seemed to be the poisoned chalice of opposition leadership, up against a dominant LNP premier in Campbell Newman.

Her tight 2015 election victory was one for the ages for the ALP. She forged a genuine bond with the nation’s most volatile electorate and delivered nearly nine years of stable and largely scandal-free government, including a challenging first term in minority.

Until the final, fraught 18 months of her tenure she was the best thing – perhaps the only thing – an otherwise lacklustre ALP outfit had going for it.

But there was always a disconnect between the affable if sometimes bumbling persona Palaszczuk sought to present, and how she conducted herself behind the scenes.

Apart from a core of rusted-on supporters and spruikers, she was not beloved by the caucus colleagues. She was too often highhanded in dealing with them, too stubborn to heed advice to move on the dud performers in cabinet, too reluctant to make the hard decisions to arrest the drift reflected by the government’s slide in the opinion polls and the plunge in her personal standing.

By the time she announced her resignation as premier and from parliament on Sunday, Palaszczuk had lost the confidence of both the caucus and voters.

Still, she could have dug in and clung to a job she professed to love. Queensland Labor Party rules go even further than the federal regime brought in after the Rudd-Gillard-Rudd circus to protect the leader from being knifed in office.

In Canberra, caucus must vote by a towering 75 per cent majority to spill the leadership of a sitting prime minister, before MPs and senators have their say along with a separate ballot of the party rank-and-file. The bar is set even higher in Queensland with the mandate that affiliated union delegates must also be polled, an almost impossibly convoluted mechanism.

To her credit, Palaszczuk saw the writing on the wall. Yet, characteristically, she took her time. She had returned in September from a controversial two-week holiday in Italy with her partner, Brisbane surgeon Reza Abid, seemingly re-energised after revealing she needed the break to get over an undisclosed medical condition. True to form, Palaszczuk had neglected to tell some cabinet ministers she would be away.

Even her sternest critics inside the government acknowledge she made more of an effort to be inclusive since turning to work. Her public declarations that she would contest the 2024 election were taken at face value by Labor MPs. What was the alternative?

A spill was not viable given the time the potentially destabilising process would consume in an election year and the other levers in the dark arts kit – drip-fed leaks to the media, perhaps a delegation from caucus to confront the Premier, ministerial resignations if it went that far – would benefit no one except LNP leader David Crisafulli, who has pulled ahead of Palaszczuk as preferred premier in some opinion polls.

Palaszczuk kept her thinking close. Labor MPs did not know of her decision to quit until a few minutes before it was announced at 11am on Sunday, at a media conference called over Tropical Cyclone Jasper. Palaszczuk said she made up her mind while attending national cabinet in Canberra last Wednesday.

“I was sitting there thinking, this is the fourth prime minister, there are all these new faces around the cabinet table … and I thought to myself, renewal is a good thing,” she said.

She revealed she had taken soundings from former West Australian premier Mark McGowan, who bowed out unexpectedly in June. Her other great friend, Daniel Andrews, quit as Victorian premier in September.

There was a final twist. Palaszczuk did something she has refused to do during all her time in the hot seat: she nominated a successor in Steven Miles, her deputy since 2020 and leader of the parliamentary Left.

Regarded as a capable minister, Miles is strongly supported by “Blocker” Bullock and has a tight relationship with the union powerbroker that predates his entry to parliament in 2015. They speak regularly.

But Miles’ image took a hit during Covid when he was state health minister and became an unconvincing “attack dog” for Palaszczuk against Scott Morrison’s then federal coalition government. Opinion polls show Miles was savagely marked down by voters, and his standing is yet to recover.

As the jockeying intensified between his rivals, Health Minister Shannon Fentiman, also of the Left, and Treasurer Cameron Dick from the Right, Miles’ camp insisted last night that he had the numbers to become Queensland’s 40th premier.

Labor’s hope is that an orderly leadership transition can be negotiated without the need for a contested ballot for the leadership – and the delay and trouble it would entail – but there was no sign of either Fentiman or Dick backing down.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout