This innovative move addresses what had been a glaring omission in our national security apparatus. State premiers and chief ministers make the big decisions on critical infrastructure, higher education and the integrity of the state political systems from foreign interference, yet on the whole they have zero national security competence.

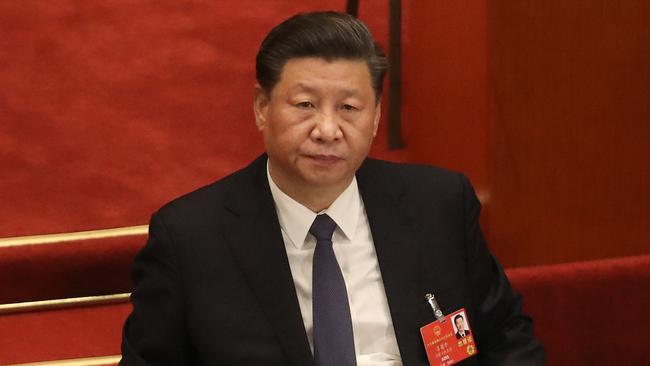

This was evident in Victorian Premier Mr Andrews’s foolish decision, against national Australian policy, to sign up to Beijing’s Belt and Road initiative, and in the earlier decision by the Northern Territory government to hand over a 99-year lease on the Port of Darwin to a Chinese company.

It is essential therefore that state governments draw on the expertise of federal agencies in national security.

It would be no bad thing for the Prime Minister to have regular conversations of this style with the state premiers.

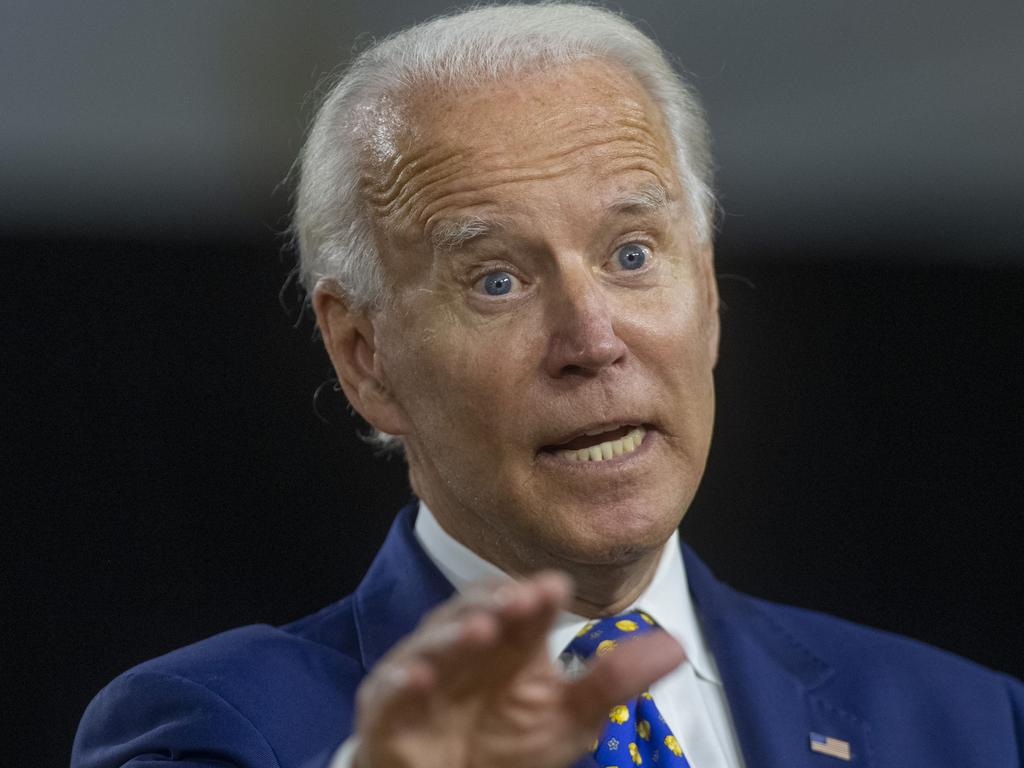

Morrison on Wednesday also highlights the worsening strategic circumstances Australia faces in a keynote address to the Aspen Institute, to be delivered online.

In security terms, the Prime Minister says, “the jungle is growing back … we need to tend to the gardening”.

Though the speech is diplomatically worded, the Prime Minister calls on Beijing to “enhance regional and global stability”.

While saying Australia has welcomed China’s rise, Morrison comments that “with economic rise comes responsibility”.

In a stark, unadorned catalogue of the new challenges, Morrison declares that: the Indo-Pacific is the epicentre of strategic competition; tensions over territorial claims are rising; the pace of military modernisation in the region is unprecedented; cyber attacks are increasing; democracies face new threats of foreign interference; free societies are at risk of being manipulated by disinformation; economic coercion is increasing; trade rules have become obsolete.

This is an undeniable list of major dynamics that make Australia’s strategic environment both more complex and more dangerous than it has been for decades.

And at the heart of each is China.

The Prime Minister rightly calls for security and trade policy to be much better integrated. This need in part lies behind his reaching out to the premiers on China. The premiers are very active on trade but know nothing of foreign and security policy.

Morrison repeats his earlier criticism of negative globalism and calls for international institutions to work at the behest of states towards real solutions to problems.

In a formulation that will annoy all woolly-headed academic theorists of international relations, he says that good international institutions are a symptom, not a cause, of a well-functioning society of states.

This is a realist approach by a hard-headed leader.

The premiers, and everyone else, should take note.

Even in the midst of the COVID-19 crisis, the most important national security issue facing Australia is China, as evident in the historic move by Scott Morrison to brief all state premiers on China (except Daniel Andrews, who needs such a briefing the most but couldn’t attend) as part of the national cabinet process.