Grampians ban in place despite sites unknown

Bureaucrats were still desperately hunting for the location of all rock climbing sites in the Grampians days after a ban.

Bureaucrats were still desperately hunting for the location of all rock climbing sites in the Grampians days after banning the sport across the Victorian national park.

Despite secretly plotting since 2017 to evict or restrict climbers in the sport’s Australian heartland, new documents show the government was still questioning where all the climbing was occurring.

Parks Victoria asked climbers on March 4 for any maps of sites they had to help determine how they fitted within eight new special protection areas that have gutted climbing in the park.

The government is also still determining where the most sensitive Aboriginal cultural heritage sites are, despite banning the areas, about 260km west of Melbourne, to climbers.

The newly formed Australian Climbing Association Victoria obtained the emails under Freedom of Information laws, which show that an agency in Premier Daniel Andrews’ department was involved in the banning process.

On March 4, Parks Victoria manager (stakeholder relations) Lucy Marshall wrote to Victorian Climbing Club officer Tracey Skinner seeking help to chart where climbing occurred. This was after Parks Victoria maps were published in late February showing the banned areas but not pointing out the affected routes.

“To inform future conversations, it would be most useful if you have any mapping information regarding climbing sites you are able to provide us?,’’ Ms Marshall asked Ms Skinner.

“We can then also overlay this with the current protection area boundaries.’’

On February 28, the VCC had complained to Parks Victoria that it had been blindsided by the ban announcement.

The VCC had sought maps from Parks Victoria detailing where the eight protection zones were to enable it to tell its members where climbing was banned and to determine what routes may be affected.

Ms Skinner said Parks Victoria’s release of the protection zones had alarmed climbers and left the VCC unable to explain what was going on. The maps did not contain climbing routes.

She urged Parks Victoria to help it sell the message of the ban.

“At the moment, all it seems like is that they are losing everything. This is not a positive move forward for us and makes it more difficult for the community to continue to have faith in us,’’ Ms Skinner wrote.

Parks Victoria had previously negotiated with the VCC about concerns regarding climbing behaviour but did not detail the extent of the bans until it was too late.

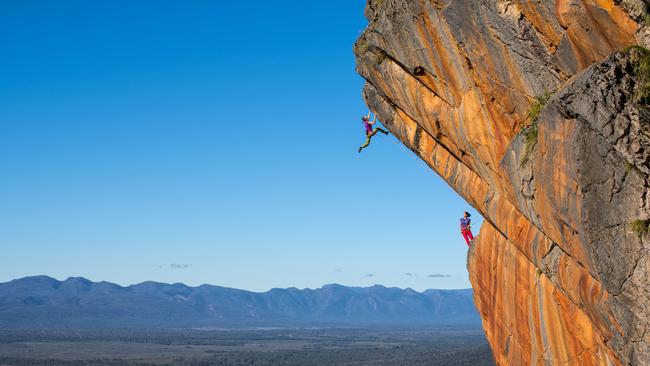

Parks Victoria and Aboriginal Victoria have accused climbers of desecrating important sites by using bolts to support their climbing, damaging indigenous artwork, tramping on vegetation and lighting inappropriate fires.

Parks Victoria said that in partnership with traditional owner groups, it was preparing a new management plan for the Grampians.

“While this plan is not being developed in response to changes to rock climbing access in the Grampians National Park, it will provide longer-term direction on matters such as recreational activities,’’ a spokeswoman said.

“The scope of this project also includes environmental conservation, cultural heritage and protection of Aboriginal rock art, tourism opportunities, safety and visitor experience.’’

Parks Victoria was being driven, at least in part, by the legislative requirement to protect indigenous cultural heritage.

As a compromise, the VCC backed a clampdown on the development of new climbing routes in parts of the Grampians but the government went instead with the wide ban, estimated to be more than 500sq km in the park.

A second climbing lobby group, the Australian Climbing Association Victoria, which obtained the emails under FOI laws, said the government bans could wreck the sport in Australia.

Association spokesman Mike Tomkins said the government’s “investigation’’ of climbing sites had been limited to social media and an online climbing site.