DURING the past month, Australian public debate on sovereign wealth funds has taken a surprisingly cynical turn. At the same time as two states - South Australia and Western Australia - took steps towards establishing their own funds, federal parliament voted against establishing a national fund, Treasury secretary Martin Parkinson queried their fiscal benefits and a series of reports and articles cast doubt on the appropriateness of these investment vehicles for Australia.

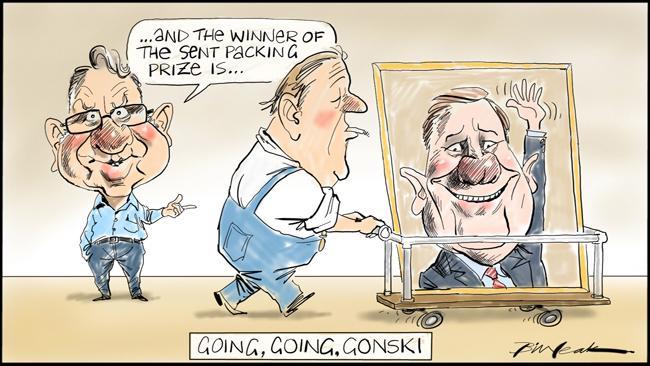

Some of this criticism targeted the Future Fund, Australia's only national sovereign fund. As I reflect on my six years as Future Fund chairman in the lead-up to my departure, it seems timely to offer some perspective.

Let me start with the question of intergenerational equity since, contrary to those who consider this justice-based rationale for a sovereign fund "embarrassing" or the "last refuge" of "bad economists", questions of fairness to future generations are not simply a matter of morality, they are of fundamental importance to sound economic policy.

Politicians routinely strip value off the future. Nowhere is this more evident than in the ailing economies of the eurozone or Australia's infrastructure deficit. Where government initiatives so often fall victim to short-termism, pork-barrelling or overspending, sovereign funds offer a unique means of decoupling public capital from election-cycle opportunism.

This is critical when a nation faces foreseeable future liabilities. The Future Fund Act states that its assets accumulate to provide for unfunded public sector superannuation, due when the needs of an ageing population will begin to strain commonwealth finances. Even if we accept that tomorrow's children may be richer on average than today, the costs of caring for their parents and grandparents will also be greater. This principle, that such costs should be borne by those who generate them, underpins Australia's world-leading superannuation system.

The Future Fund, like other sovereign funds, provides a similar function, allowing each generation to collectively shoulder the future financial burdens it creates.

But let us for a moment question the assumption that future generations will always be richer. Sceptics about intergenerational wealth transfers assume each generation is better off than its predecessor. This is a strange argument to run against the backdrop of the financial crises across much of Europe and Britain. Indeed, Australia's generation Y, facing growing wealth inequality and being priced out of the housing market, may find the idea they are richer than their parents dubious.

Government must position itself to ease the challenges of foreseeably worse-off generations. Few Australians bemoan the road and rail networks, electrical grids, dams and water reticulation and drainage systems bequeathed to us by past generations.

Why would the accumulation of financial assets to prepare for and lessen the burden of known future liabilities prove to be an exception?

Moreover, the assumption of greater future wealth is especially problematic in the Australian context. SWF cynics tend to downplay the finite nature of our resources. Recent calculations done by Treasury economists Phil Garton and David Gruen indicate that Australia has a resource life of at least 70 years, based on the weighted average of reserve projections in iron ore, black coal, gold, crude oil and gas reserves.

Seventy years may seem like infinity, but so, one may argue, may two decades of continuous growth. During the past 20 years, Australia has enjoyed an average of 3.3 per cent in real gross domestic product growth annually. Yet Australia has surprisingly little to show for this lengthy uninterrupted expansion in key policy areas. Despite the Future Fund and the modest nation-building funds, Australia remains a savings-short nation and suffers a considerable infrastructure investment gap. Further, the terms of trade for commodities are highly volatile. The next 70 years could be comparatively advantageous or disadvantageous for Australia.

Even if we could guarantee fortuitous times ahead, such growth is meaningless if a country cannot convert its income into wealth and its savings into investment. Sovereign funds focus governments on priority areas for long-term investment by ring-fencing portions of public capital for specific needs and quarantining these funds from the politicised budget cycle.

Again, critics are quick to overstate the risks of setting aside large pools of public assets. Sovereign funds are accused of encouraging politicians to borrow more than they should, offering tempting pots of cash for governments to raid and being vulnerable to future misuse on account of their fungibility.

Such risks result from poor governance, not sovereign funds per se. Consider the track record of the global sovereign fund community. Incidents of fund-raiding in Russia, Kuwait and Ireland during the financial crisis stand out as isolated examples from among the world's more than 60 funds. Of the longstanding funds, there is no evidence governments have sought to abuse their growing wealth, or become more reckless or irresponsible in their public spending as the value of these funds has grown. The effective decades-long management of some of the world's largest funds in Singapore (1974), Abu Dhabi (1976), Alaska (1976), Norway (1990) and Malaysia (1993) suggests a correlation between responsible spending by governments and the presence of a sovereign fund.

Juxtapose this pattern with the profligate spending of eurozone countries such as Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain, and the hefty borrowing of the US and Britain, all of whom lack a sovereign fund. On this basis, one could speculate that the establishment of a sovereign fund reflects a government's tendency for responsible economic management, not a reason for its abandonment.

Australia might have pursued this path. The counter-factual to establishing the Future Fund is that the original $60 billion seed figure stayed in the national accounts as available surplus, and was likely spent as soon as the global financial crisis hit. This would have lessened the need to borrow, but it also would have meant this capital was unavailable for long-term return-seeking investment.

On this point, critics still complain of low real returns, arguing the Future Fund is bad value for taxpayers. Two points are crucial in reply. For one, the Future Fund should be judged by its long-term rate ambition of 10-year rolling periods. Recall the fund's inception date in 2006 coincided with the onset of the most severe financial crisis since the Depression and it has been operational for only five years.

It is disingenuous to focus on this first slice of the fund's history to assess its value as a long-term asset manager.

Second, management of these assets is as much about preservation as it is about augmentation. In its first six years, the fund maintained its stock of capital and created a real return.

If the positive forecast for continued growth in Australia is realised, imagine what sort of returns a substantial national fund based on annual transfers of mining royalties could generate investing in post-crisis conditions.

David Murray is chairman of the Future Fund board of guardians.