Flatten coronavirus infection curve or cases will swamp hospital ICUs

Australian doctors may soon be faced with agonising decisions about who to save and who to let go.

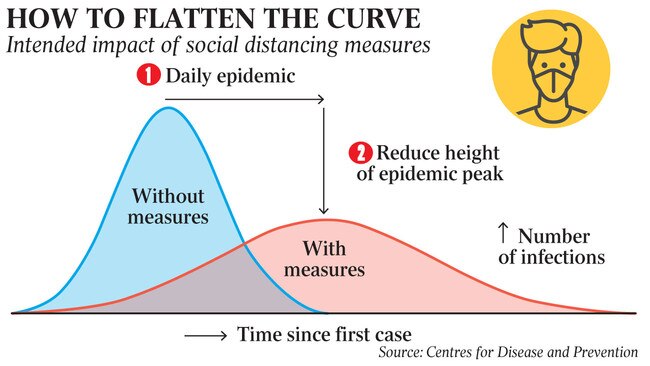

Health authorities, racing to control the coronavirus, face a life-or-death challenge: flatten the rate of infection or face a situation where hospital doctors will need to make agonising decisions about who to save and who to let go.

COVID-19 infections are doubling every six days. With Australia’s tally jumping to 199 late on Friday, the number of cases will have passed 10,000 in less than six weeks unless the spread is slowed.

NSW Chief Health Officer Kerry Chant this week warned 1.5 million people in the state are likely to become infected, yet the nation has only 2000 intensive care beds.

The coronavirus fight has been complicated by a potential shortfall in testing equipment, which has forced authorities to limit the number of tests even as some health experts call for mass testing to tackle the arc of infection.

The government revealed on Friday it was battling a shortage of chemicals used in the tests. This has forced West Australian health authorities to place strict criteria on who is tested.

Even before the impact of the virus is felt, there are no spare intensive care unit beds in hospitals, and the number of ventilators for patients needing help to keep their lungs pumping is limited.

Australia’s 695 public hospitals with a total 62,000 beds have 100 ICUs with an estimated 1485 beds. The nation’s 630 private hospitals have 33,100 beds, including 51 ICUs with 538 beds.

While many people infected by the virus will have only mild symptoms, the worst-case scenario indicates 15 per cent will become seriously ill. This looms as a challenge far beyond the capacity of their intensive care units.

Australasian College of Emergency Medicine president John Bonning believes ICU capacities might need to double because of the coronavirus. He also says in a blog memo to his member doctors that hospital capacity might need to be expanded generally.

The Morrison government this week flagged a potential boost in the number of ventilators for ICUs and its health response package is intended to lift hospital resources to cope with the crisis.

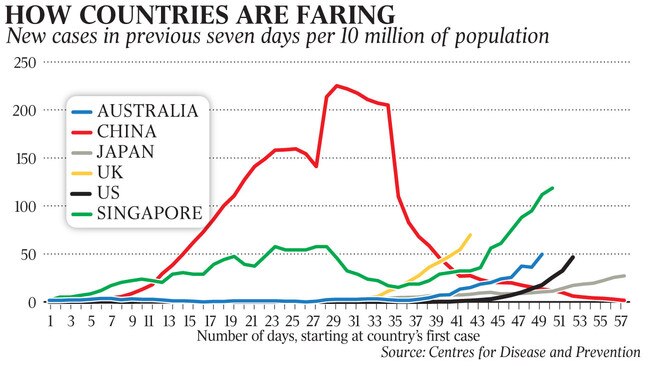

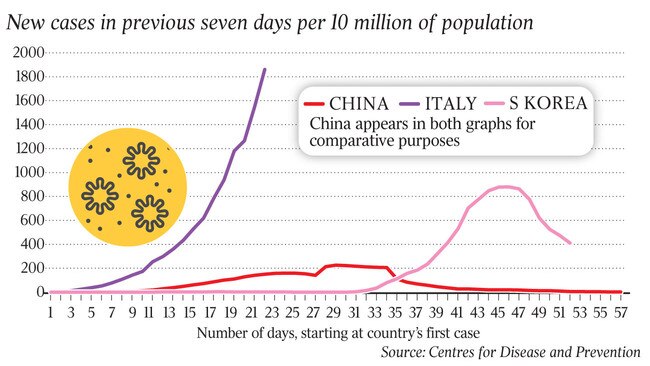

In Singapore and Hong Kong radical social distancing measures have allowed authorities to slow the spread of the virus. In Italy the virus has overwhelmed hospitals and forced doctors to prioritise younger patients over the elderly.

Serious policy differences have emerged among health experts about whether the government’s approach is tough enough to slow the virus’s spread to allow the health system to cope.

Even as the government moved to stop gatherings of more than 500 people from Monday, a paper published in Lancet casts doubt on whether this is tough enough. It said banning mass events or closing schools would not be enough. Containment of people to their suburbs may be required.

“What has happened in China shows that quarantine, social distancing, and isolation of infected populations can contain the epidemic,” the paper says. “Singapore and Hong Kong … provide hope and many lessons to other countries. In both places, COVID-19 has been managed well to date … by early government action and through social distancing.

“School closure … is unlikely to be effective given the apparent low rate of infection among children … Avoiding large gatherings of people will reduce the number of super-spreading events; however … broader-scale social distancing is likely to be needed.”

Some experts warn it would be impossible for Australia to take the draconian measures required to slow an outbreak. “We don’t have a legal or political system that would readily allow for that kind of arrangement,” said Australian National University professor Shane Thomas. “We are a liberal democratic society so restricting people’s movements in that way would be politically difficult.”

Stephen Duckett, a health economist with the Grattan Institute, said the nation was at the early stages of the pandemic but a sobering fact remained. “There are not ICU beds lying idle,” he said. “The public system is already operating pretty close to capacity. If it weren’t, we wouldn’t be seeing long waiting times for elective surgery.” The problem of dealing with logistics of the coronavirus is compounded, Dr Duckett said, because an unknown number of hospital staff who contract COVID-19 would have to be isolated and therefore taken out of the frontline in treating the sick.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout