The depth of disillusionment in the two-party system is unmistakeable and the tipping point that people have talked about for years has finally arrived.

The size of the crossbench will more than double, with up to 15 independents and minor party MPs. Such an outcome is without precedent for the Australian parliament.

So too is the destruction and fragmentation of the Liberal and Labor parties’ primary vote. More than a third of eligible Australians voted for someone else. For the first time in the post-war period, one of the major parties will form government with a primary vote of less than 33 per cent.

The rupture is a rejection of the status quo that will have implications for years to come. Expect this to become the new normal, reflecting a global trend in Western democracies. Australia has finally caught up.

This is now a three-way turf war, with the task of governing becoming ever more difficult.

It presents challenges for both major parties. With the likelihood that he will form a majority government, Anthony Albanese will be able to govern in the lower house without the power-sharing arrangement that decimated its base a decade ago.

But the combined force of teal independents, whose franchised national brand exposed the weakness of the local Liberal Party campaigns, and the Greens, which ran a disciplined strategy, is now a movement and a constituency that Albanese will be unable to ignore.

It threatens Labor as much as it has ripped through the Liberal Party, if for different reasons and on different issues.

The Senate will become the critical parliamentary battleground where the expression of this new influence will be displayed.

All the pressure on Albanese is coming from an inner-city agenda. Albanese’s quick embrace of climate change as the new priority issue for this week’s meeting of the Quad appeared to be an immediate recognition of what had happened at the weekend.

Having lost at least one seat to the Greens and possibly more, there are half a dozen more Labor MPs who now have the Greens breathing down their neck. These seats will be targeted next time.

For the Liberal Party, it is an existential crisis of two competing threats. Despite the success of the teals in conquering inner-city Liberal heartland, there is equal pressure coming from the outer suburbs.

There will be a temptation within the party to view the problem as a singular issue that requires a shift to the left on the issue of climate change to win back the inner-city seats.

But this ignores the “others” vote that now occupies an equal if not greater proportion of former Liberal voters.

The fragmentation is equally if not more profound on the right. Clive Palmer’s United Australia Party, for example, did enormous damage to Liberals in Western Australia. As one conservative Liberal MP said: “the new demographic battleground for the Libs has moved to the burbs and the bush”.

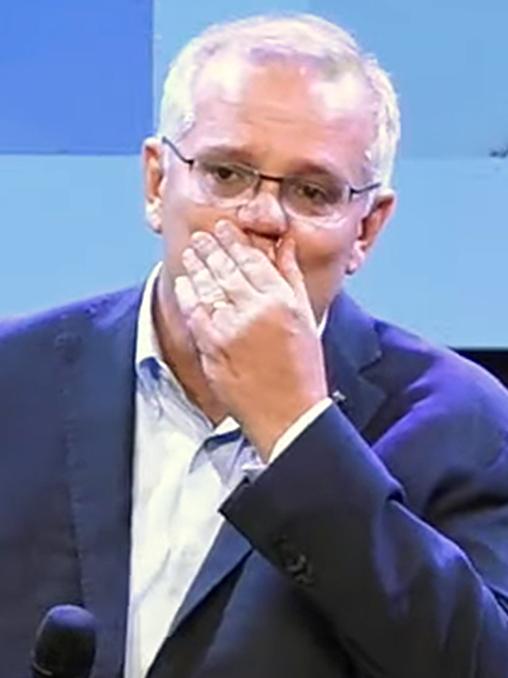

At the core of this problem for centre-right politics is the failure of the Morrison government to articulate a defining set of values that appealed to this constituency.

The election result has exposed the rise of two Australias, divided by ideology and real-world aspirations and in despair of the two major parties to address these competing concerns.

This is a watershed moment for Australian politics.