Election 2025: Major parties’ primary failings hardly a minor matter

The ALP and the Liberals have their heads in the sand over declining vote.

The essential question of the 2025 election will be whether Australia decides to embark on another experiment that redefines the political landscape.

Only once before in the post-war period has the nation embraced, and then rejected, a hung parliament. This may not be the result on the night. But if Labor is forced into minority government, it would be the second and successive time this has occurred to the ALP after only a single term in office.

What isn’t in doubt is that – for the second time since the evolution of the two-party system that emerged from the decade following Federation – both major parties will fail to secure a primary vote above 40 per cent. And likely they will be well below it.

The first and last time this occurred was three years ago when the combined vote of Labor and Coalition was just 68.3 per cent. By all accounts, a record is set to be established this weekend.

If the final Newspoll of the campaign is reflected in Saturday’s result, both parties will muster just 67 per cent of the primary vote. This would mark a historical low.

The challenge for both sides of politics will be to what degree has Australia’s two-party system, which has provided an unrivalled level of post-war stability, fragmented into a multi-party system at a primary vote level that threatens to eventually alter the equilibrium of the parliament and force both major parties to face the existential questions that both have sought to avoid?

In the post Menzies to pre-Howard era – from 1972 to the late 1980s – the combined primary vote of both major parties averaged above 90 per cent. At its peak, in 1975, it was 95.9 per cent.

The first schism occurred in the late 1980s with the emergence of the Greens. Labor senator Graham Richardson was the first and perhaps only Labor strategist to recognise the threat from the environmental movement. His view was that the Greens had taken the stage and weren’t going to be removed. Labor’s survival depended on ensuring those votes ultimately came back to Labor through preferences. Hence the pivot from the blue-collar base to inner-city activists.

While the 1987 election resulted in a combined 91.9 per cent primary vote for the major parties, it collapsed to 82.9 per cent in the 1990 election. This was driven by a six-point fall in primary vote for Labor. While this coincided with the onset of recession, the underlying combined support for both parties never returned to its previous level again.

In the two decades that followed, the average combined primary vote remained in the 80s. This was the first step change and coincided with the theory of a broader de-alignment that suggested voter loyalty to the major parties was at the beginning of a state of decline.

At the 2007 election, the combined major party vote was 85.5 per cent, a high point. But following the removal of Kevin Rudd as prime minister in 2010 this declined to 81.3 per cent, which was enough to produce the first hung parliament since 1940-41 when Robert Menzies formed government with support of the country party and two independents.

The next schism occurred in 2013, following the Gillard minority Labor government, when the combined primary vote dipped to 79 per cent. This came at the time of an emergence of parties that began tearing at the fabric of the major parties.

The Clive Palmer effect in 2013 was significant. As a disrupter, his influence became part of the existing catalyst of change. The United Australia Party took a 5.5 per cent chunk of votes in 2013 that largely scattered to One Nation and micro parties and candidates instead of going back to the major parties in 2016. Those voters look like they never went back.

The 2016 election resulted in 76.7 per cent combined primary vote. It fell further at the 2019 election to 74.7 per cent.

While the new decline was already becoming a trend, the most significant fall followed in 2022 when it fell sharply to 68.3 per cent.

The story of the decline until then had largely been one written about the Labor Party and the fragmentation of the left base. Its embrace of the activist movement at the expense of the worker base. Labor has not achieved a primary vote at an election above 40 per cent since 2007.

But the Coalition last achieved this outcome in 2019.

The May 2022 election result was regarded as an aberration within the Coalition. A realignment rather than further fragmentation. The assumption was that balance would ultimately be restored to the system.

While Scott Morrison wore the blame for the defeat, despite the Coalition’s two-party-preferred vote being higher in 2022 than in both the 2007 and 1993 election losses, this masked what has been a deeper decay that both sides have ignored at their peril.

Far from being a deviation in 2022, the emerging evidence is that Australia was in 2022 – and remains in 2025 – in the process of another but even more dramatic step change – a third phase in a series of structural declines for both Labor and the Coalition since the post-Menzies era.

The decay has become a story of the Coalition. Contrary to the view that it needed to secure its conservative base on the right, its loss of primary vote support has come on its own version of the left – the moderate vote. The teals may have come out of nowhere but the issue they campaigned on didn’t.

The irony is that the teals sapped more primary vote from Labor than they did the Coalition, thanks to the emergence of tactical voting by an enlightened electorate, but the damage was all done in Liberal heartland seats.

For the electorate, was it means, motive or opportunity or all three?

The underlying feature of this Saturday’s election and the catalyst for it not only threatens to fundamentally alter the political landscape into the future but become a permanent feature of it.

The Liberal Party’s post-2022 election review, conducted by former Liberal campaign director Brian Loughnane and Liberal senator Jane Hume, illuminated the consequence of all this.

“There are now significantly less ‘safe’ seats held by either major party,” the review said. “This is a trend in electoral results over the last seven electoral events. In 2004, 86 seats were decided on primary vote. In 2013, 50 seats were decided on primary vote alone. In 2022, it was 15 seats.”

A defining issue of the past two decades, which has infected every election since, has been climate change and the failure of both major parties to attend to both their internal and external constituencies in a new polarisation.

There have been other issues, social and economic that have affected outcomes. Border protection and immigration have also been dominant features.

But the gradual decline remains evident and began almost 40 years ago.

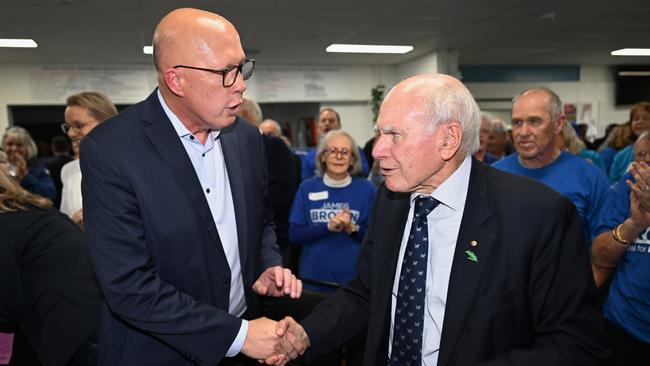

Former Liberal prime minister John Howard says of the historical primary vote decline that the world has become more complex with the political divisions less clear. A cycle of state dependency has emerged.

How sustained this is will be determined by this Saturday’s election result. The transformation and disruption of new media in the digital age has both coincided with and facilitated a fundamental alteration of the relationship between political parties and voters.

Yet there are more enduring and fundamental factors that underpin these forces.

“The political world is a lot less binary or clear cut division between the two sides of politics,” Howard told The Australian.

“Twenty or 30 years ago the debate was about the level of balance, to what extent the government should involve itself in the economy. The centre right was arguing it shouldn’t be involved at all and the centre left was saying the government should be heavily involved. That’s broken down a bit because the left has accepted the government can’t run everything.

“But when it came to defence, national security and foreign affairs, it was very much a battle between the east and the west. It’s still substantially that but it has lessened and we have now a far more complicated situation.

“I think those two issues were presented as a more clear-cut division between the two sides of politics, even going back to the 60s.”

Richardson is convinced that the major parties’ vote decline is not over yet. “I hope I’m wrong,” he told The Australian.

“But I think there is more to come. Growing up you had three (television) channels to look at it …. now you have 103, that’s been a big change, People are more fluid these days.”

Richardson agrees climate change has played a role in the post 2007 change.

“People get so passionate about it and it has presented great difficulties, for both sides to deal with … In the old days we voted the way mum and dad did …. things have changed. And issues like climate change have been hyper politicised.”

What has masked the consequences of this decline has been Australia’s exhaustive preferential voting system in federal elections. This has acted to minimise the impact. The alienated end up going back to a major party because the system forces them to.

And this is why hung parliaments have been the exception rather than the rule.

For Labor this means that the Greens will increasingly become the factor that decides whether Labor can form majority or minority government.

It is less clear how the centre-right manages this problem.

The question is how long this division can be sustained for both the major parties before more existential questions are asked.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout