Election 2022: Mellow Anthony Albanese belies angry youth

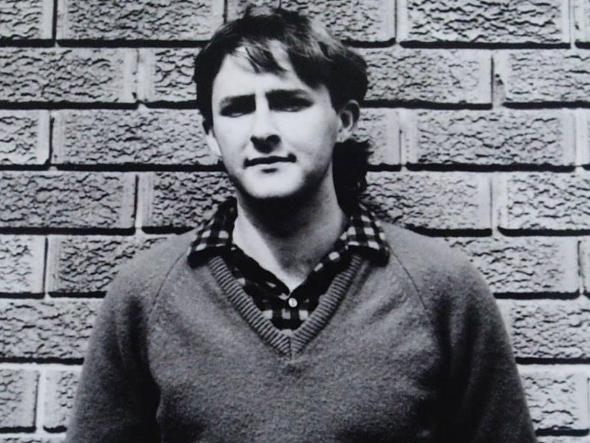

The Anthony Albanese presented to voters in this election is very different to the angry young man who once railed against his party’s leaders.

The Anthony Albanese presented to voters in this election campaign – pragmatic, moderate, even mellow – is very different to the angry young man who once railed against his party’s leaders on almost everything.

He is remembered as a “super-militant” and “tear-down-the-house guy”. As a fierce Labor left warrior working in his party’s Sydney HQ in the 1990s, Labor chieftains even devised a plan to keep an eye on him.

While Albanese was out of the country attending a US study course, they moved his fully enclosed corner office to a new “glassed-in” version. Located deliberately at the centre of the open floor plan, they called it the fishbowl.

Those close to him say Albanese underwent a genuine transformation when he entered parliament in 1996, realising that old-fashioned activism did not work.

But the man who could be Australia’s next prime minister appears to have sanitised his past as the election campaign gets going in earnest.

Much of Albanese’s job during his first week on the campaign trail has been to introduce himself to voters – but his verbal contortions have left him bruised. Dismayed party hardheads are already calling for a campaign reset. As one wily Labor figure, a supporter of Albanese, laments: “He caught himself in a spider’s web.”

A day-one gaffe in Launceston when Albanese was forced to admit he didn’t know the unemployment rate, or the Reserve Bank’s cash rate, was just the start of a horror week.

Labor’s campaign team had hoped a short, sharp apology at a second Launceston media doorstop called soon after could stem the damage for failing to recall to two key economic statistics. “I’m human. But when I make a mistake, I’ll fess up to it,” he said.

But Albanese did not keep to the script as the days passed – repeat the apology if asked again and move on.

Instead Labor’s leader kept talking, and talking, trying too hard to pump up his economic experience. He insisted he’d been “an economic adviser to the Hawke government” in his early years and quoted his university credentials.

But wasn’t Albanese employed as a junior “research officer” for Tom Uren straight out of university? Or an “electorate officer” for Uren as it has also been reported?

What about Uren? Wasn’t he a minister in Hawke’s government with a junior non-economic portfolio who did not sit in cabinet? Wasn’t Uren a hard left-winger, like Albanese at the time, opposing almost all of the economic agenda pushed by Hawke and Paul Keating?

No, Albanese insisted, he was an economic policy adviser. “That’s just a fact.” Uren and Keating had a “fantastic relationship” too.

Labor’s campaign team wanted Albanese to highlight questions about Scott Morrison’s authenticity, not open the door to his own. The problems were compounded by Friday with confusion over Albanese’s support for maintaining offshore detention and a lack of costings for his urgent health care plan.

Labor’s leader does have experience as a cabinet minister for six years in the Rudd and Gillard governments, and briefly as deputy prime minister.

But he created an unnecessary mess for himself – overstating the description of “research officer” provided in Albanese’s official parliamentary biography – by rating himself an economic adviser as though he was seemingly inside the Hawke policy tent.

Some Albanese supporters point to economic submissions he wrote for Uren for those occasions when the minister spoke outside his portfolio of local government and territories. Albanese, they say, also accompanied Uren as an adviser to a UN economic conference.

But most of the economic submissions Albanese wrote for his boss Uren seem to have been political documents critical of measures Bob Hawke and Paul Keating wanted to implement.

In her biography of Albanese, journalist Karen Middleton writes that during his stint as Uren’s research officer from 1985 to 1989, the ALP parliamentary left faction convenors Bruce Childs and Gerry Hand blasted their own government’s budget measures using briefing notes “prepared for them by young Left staffers, including a certain research officer working for Tom Uren”.

Albanese was very much outside the Hawke-Keating tent. At the same time working for Uren, having started as a 24-year-old straight out of university, Albanese was prominent in NSW Young Labor.

Middleton quotes Albanese’s successor as Young Labor president Mal Larsen from that time: “Much of Young Labor’s activity in that time was condemning the Hawke Government for horror budgets cutting government spending and welfare, and the introduction of HECS.”

At the annual weekend NSW party conference shortly before the Hawke government’s 1985 tax summit, Keating outlined his proposal to pay for tax cuts with a consumption tax.

Party left activists including Albanese protested during the then treasurer’s speech by filling the air with fluttering Monopoly money. “That was one of the actions that didn’t endear Young Labor to the party leadership,” Albanese would later tell Middleton.

The persistent theme presented by Middleton throughout her biography is that the young Albanese was always angry and fought for his cause as a self-declared socialist. It was John Della Bosca, then NSW party secretary, who called him a “super-militant” and “tear-down-the-house type of guy”.

Even Uren, in his memoir Straight Left, had to calm down some left comrades who told him: “Oh, you’re putting a young Trot on your staff.” Uren, who took a shine to Albanese, and would soon become a father figure in his life, disagreed. “I haven’t! I don’t think you’re right,” he said. According to Uren, he “wasn’t convinced the young man was as far Left as that”.

Albanese’s Labor pedigree was inherited from his mother, a party loyalist. But the underlying reasons for anger which always seemed to burn not far beneath the surface during Albanese’s earlier life came from his lived experience. Brought up by a single mother who suffered serious arthritis, Albanese harboured a personal sense of class. He lived with his mother in Housing Commission premises at Camperdown in Sydney’s inner west. His mother’s access to health services was limited, and he often looked after her. They were poor. There was often not much in the fridge to eat.

One close observer tells The Weekend Australian: “As a young man at university, he was deeply political. He saw himself as a representative of the repressed classes.”

Another says: “The psychology of this is the absent father problem. Tom later became his substitute father – he didn’t actually have a father. Tom could do no wrong, as far as Anthony was concerned, and I think a really strong emotional bond developed between them. So, while ever Tom keeps being brought into it, it can cause emotional confusion and clutter up his judgment. Which is what happened this week.”

At Sydney University, as Albanese told the campaign media pack this week, he studied “orthodox” Economics. He also took a highly controversial course called Political Economy, essentially a critique of straight economics using Marxist theory to attack free market thinking.

While studying Political Economy, Albanese was a student activist at the forefront of a fight against the university hierarchy’s moves to scrap the subject. Its left-wing lecturers Ted Wheelwright and Frank Stilwell were accused of allegedly indoctrinating students with ideology. University protests reached a peak in Albanese’s third year when he led an occupation “sit-in” in the Economics faculty building. Police were called. Albanese and others faced disciplinary charges, though they were later dropped.

Albanese graduated with a Bachelor of Economics. Detail of his course work is hazy in Middleton’s book with her statement that his studies involved a “double major in Industrial Relations and majors in Government and Economics”.

When Uren employed Albanese straight out of university, Uren was very vocal in ALP left politics but his influence from the Whitlam years had waned.

Hawke had to appoint Uren to his ministry when Labor won office – at the Left’s request – but he relegated Uren to a non-cabinet junior portfolio. Economics did not figure much, if at all, in local government. Funding came from Treasury.

Uren was prescient in recognising early on that his protégé Albanese would one day be “a very great leader of the Labor Party, and particularly the Left”. In the meantime, Albanese’s views mirrored those of his boss: opposition to floating the dollar, deregulation of the economy including the entry of foreign banks, privatisation of government assets, lowering of tariffs and the proposed consumption tax, dumped after pressure from Uren and others.

Senior Labor insiders dismiss Albanese’s suggestion this week that Uren’s relationship with Keating was “fantastic” when Uren was frequently an opponent of government policy.

“You can be pretty certain there was some invective directed at Tom,” one said. “Paul would have made a few passing flicks at him – but Tom wouldn’t have troubled Paul much because Tom was pretty useless by that time.

“Tom was formidable in the Whitlam government. He had numbers in the caucus then who followed what he said, and he was regarded in the party as a guru of the left, he had some clout.

“By the time he was a junior minister in the Hawke government, he was nuthin’. He was on the way to the pension.”

When Albanese left Uren’s office in 1989 to take the ALP Left’s allocated spot as assistant secretary in the NSW party head office, he faced a hostile welcome from the dominant Right leadership under Della Bosca.

Albanese was given a key to his corner office, but claimed he was denied access to membership and other records. Even the photocopier and fax machine.

When some of Della Bosca’s deputies arranged a new “glassed-in office” to be built for Albanese on the middle of the floor where all could observe him, and changed the office locks, Albanese fought back. The arrangement was reversed and dismissed as “a joke gone wrong”. But it was a sign of just how Albanese’s militancy was regarded internally.

The fundamental change in Albanese’s outlook seems to have occurred soon after he was elected to parliament in 1996 as the Labor member for Grayndler in Sydney’s inner west.

One insider who knew him well from university always wondered if he’d been “playing a role” in the past, especially when many disputes between the left and right amounted to “posturing”. Regardless, a new pragmatism seemed to take hold and the anger of Albanese’s youth subsided. He also had a family now.

“He’d had some engagement with the right machine. He’d come to the realisation that protesting as an activist wasn’t effective in getting outcomes, and that achieving government was where you could pursue effective policies to benefit people.

“He would have realised that his protests over Political Economy at university didn’t get him anywhere.”

“I think that Anthony has genuine care for people who’ve missed out and didn’t have opportunities. In a practical way, being manager of government business in the Rudd government was a strong lesson for him.”

Inside Labor, there are hopes of no more slip-ups over the next five weeks. Optimists in the party use a football analogy that even the best players drop the ball sometimes. But as one put it: “They don’t drop it from the kick-off.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout