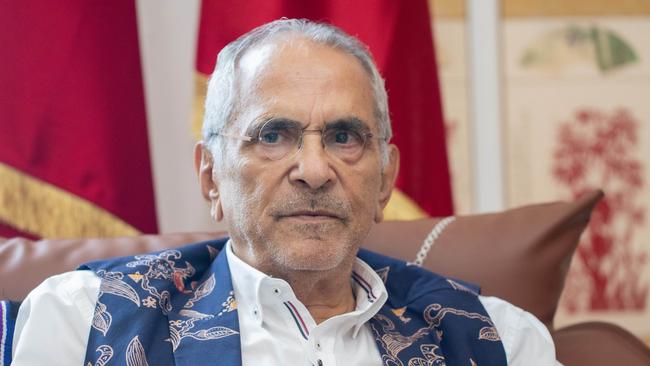

East Timor President Jose Ramos-Horta lobs China grenade ahead of visit

East Timor President Jose Ramos-Horta has warned his government will look to China or Kuwait to help it develop the Greater Sunrise oil and gas fields if Australia does not back its preferred option.

East Timor President Jose Ramos-Horta has likened Anthony Albanese to a neglectful godparent who never visits, and warned his government will look to Chinese or Kuwaiti investors to help it develop the Greater Sunrise oil and gas fields if Australia does not back its preferred option of a risky and expensive pipeline to the country’s south coast.

Mr Ramos-Horta says it is time the Australian government looked beyond simple economics and saw East Timor for what it is – “part of its national security, national strategic area of interest”.

Had it done so “it would have supported the pipeline to Timor long ago”, he told The Australian.

“It would have invested much more in Timor Leste than foreign aid. And the Australian Prime Minister would have visited East Timor several times. Anthony Albanese has not visited. He sent Penny Wong to make up for that. We like Penny Wong but she’s not the PM,” he said, using the alternative name for his country

The comments from the veteran diplomat underscore the often fractious relationship with Australia’s closest neighbour – located just 600km north of Darwin – as it faces a looming economic crisis brought on by mismanagement of its multibillion-dollar Petroleum Fund.

In a wide-ranging interview ahead of his visit to Australia next week, Mr Ramos-Horta said he believed Mr Albanese’s late Labor Party mentor Tom Uren would advise his protege to “stop the crap” and “go and visit Timor Leste and increase support”.

“When the Prime Minister doesn’t even bother visiting you how can we say, ‘Ohhhh, East Timor and Australia (is a) very important relationship.”

Australia should “fully back” Timor’s Greater Sunrise ambitions and underwrite the insurance risk to provide greater incentive for investors, he added.

Canberra is clearly on notice in East Timor, where in recent months the government has cancelled a flagship Australian government-supported social protection scheme and suspended delivery of two Australian navy patrol boats.

Deakin emeritus professor and long-time Timor watcher Damien Kingsbury believes Dili is sending warning signals ahead of an independent feasibility study into development options for Greater Sunrise that failure to support its ambitions could have strategic consequences, notwithstanding doubts over Chinese enthusiasm for investing in the project.

“There’s a reason it still hasn’t happened – they see the same viability challenges that everyone else does,” says Parker Novak, a nonresident fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Indo-Pacific Security Initiative and former International Republican Institute director for East Timor. Still, he agrees Greater Sunrise is “probably the most important variable driving the future of the (Australia-Timor) bilateral relationship”.

Diplomatic ploy

Mr Ramos-Horta bristles at suggestions he is playing the China card to leverage more support from Australia, and says it is in Timor’s national interests to build relationships with all great powers.

But he adds: “If China didn’t exist as it is, God, where would poor countries go when they’re completely ignored by the West, as Australia ignored Pacific island nations for decades and treated them like their little backyard?

“The US, Australia, all descended on islands only when China decided to have a little maritime agreement with the Solomon Islands. It’s not a naval base. The Chinese want some guarantee, if their businessmen are attacked (they) can help their people.”

Twenty-five years since the Timorese voted overwhelmingly for independence from Indonesia, Asia’s youngest nation is hurtling towards the edge of a so-called fiscal cliff. Falling over it could plunge the impoverished country into bankruptcy and famine.

Billions of dollars in proceeds from its spent Bayu Undan gas field is projected to be gone by 2034 with no income source yet to replace it, though there is a proposal on the table to turn the empty Bayu Undan well into the world’s biggest carbon capture and storage facility.

East Timor’s Petroleum Fund was supposed to last generations but currently finances more than 80 per cent of the annual state budget. Now in a race against time to prevent economic collapse, the Timor government sees the Greater Sunrise gas and condensate fields that stretch across its Timor Sea boundary with Australia as vital to its future.

Income from those fields cannot come soon enough. Exploration has stalled for years because of disputes between joint venture partners over where the gas should be refined, and between Canberra and Dili over maritime borders which the Timor government sees as having contributed to its current predicament.

With the border finally settled, Mr Ramos-Horta says an agreement on a legal framework and preferred development option should be reached by the end of the year between Timor’s state-owned Timor Gap majority stakeholder, Australia’s Woodside, and the Australian arm of Japan’s Osaka Gas.

The independent concept study, a draft of which is already circulating, is intended to guide that decision by evaluating new technologies, as well as the socio-economic, safety, environmental, strategic, and security benefits of the various options. Yet asked if his government was prepared to accept the Darwin option should the study show it to be the better option – as widely expected – he told The Australian: “Without any irresistible offers from Australia, of course Timor will walk away.”

Mr Ramos-Horta says he understands concerns over the risks and costs of Tasi Mane, but insists those costs would be mitigated by Timor’s cheap labour and easier tax regime. “(If) the pipeline goes to Australia, we are paying Australian workers,” says. “How does this make sense? For us, there are no difficulties developing partners for Greater Sunrise.”

Timor would prefer to work with its current joint venture partners and believes that together Australia, Timor and Indonesia could b major energy powers if they joined forces.

But, equally, the Chinese are “very interested in Tasi Mane”, he insists, as is a private Kuwaiti investment fund that says it’s ready to invest $US12bn in the project.

Analysts say bringing Greater Sunrise on stream buys East Timor time to start diversifying its economy, reduce its dependence on imports and transition from a generation of resistance-era leaders who, having fought so valiantly for an independent nation, have proved poor economic stewards.

East Timor’s economy has flatlined in recent years, down from an average growth rate of 5 per cent in its first decade of independence to 1 or 2 per cent in the past 10 years. Youth unemployment is above 30 per cent and productivity has plummeted, according to a recent World Bank report.

Not everyone is convinced Greater Sunrise is the answer to those problems given some doubts over the commercial feasibility of an expensive fossil fuel project with a long lead time to production in the age of global warming.

Even if an agreement were reached tomorrow, it would take six to eight years for income to flow and nobody knows what the market price for natural gas will be by then, says Charlie Scheiner, a development analyst with Dili-based NGO La’o Hamutuk.

Woodside has long-argued Timor’s Tasi Mane option is economically unviable. Its preferred option, to pipe the oil and gas to an existing facility in Darwin, could bring the project on stream several years quicker.

None of those arguments have swayed Xanana Gusmao, the country’s most celebrated resistance hero, who sees Tasi Mane as his political legacy and a fundamental issue of sovereignty.

Relationship reset

Foreign Minister Penny Wong may not have been the guest Timor was looking for when she visited in 2023 but her message landed well when she did.

Australia had made mistakes with Timor and had been wrong to drag out maritime boundary negotiations and from now on would be a good and respectful friend to Timor. “That means listening carefully to your interests and priorities. That means being a partner who will support the sustainable growth of your economy and deliver the greatest wealth and security for your people,” she said.

“That is why Australia is so deeply committed to working with East Timor to realise the development of Greater Sunrise.”

It was the reset both countries needed after years of tensions over allegations of Australian spying during maritime boundary negotiations, and what the Timor government saw as transactional development aid linked more to Australian interests than its own.

Mr Ramos-Horta said Timor and Australia “have the best possible relationship”.

Yet the government’s decision to suspend the May delivery of two patrol boats and cancel a DFAT-supported cash payments program for mothers to counter high rates of child malnutrition, sent shockwaves through the embassy and the development community.

The Guardian patrol boats were part of a 2017 agreement struck with the previous Fretilin-led government that included maritime training for Timorese naval personnel and Australian assistance to upgrade Dili’s Hera port. Timorese navy commanders are said to be fuming given their lack of capacity to prevent illegal fishing inside their waters.

Mr Ramos Horta told The Australian there was “no universe in which Timor could go it alone on maritime security without Australia given the proliferation of illegal fishing and other crimes in its waters”.

The government insists it is simply reviewing the suitability of projects.

Fretilin chairman and former prime minister Mari Alkatiri told The Australian the project cancellations – along with a decision to scrap low-cost World Bank and Asian Development Bank loans for water, health and education projects – would scare investors, and that walking away from Timor’s Greater Sunrise partners “would be the biggest disaster”.

“Nobody is going to invest in a country where there is no continuity of policy,” he said.

Last month, East Timor marked a quarter of a century since the Australian-led Interfet peacekeeping force swept into Dili to end an orgy of pro-Indonesian violence triggered by its independence vote in September with a series of moving events.

Guests of honour included former Australian Army commander Sir Peter Cosgrove and UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres.

At an informal reception in the Chinese-built Presidential Palace last week, Mr Ramos-Horta thanked dozens Australian and New Zealand Interfet veterans in matching T-shirts bearing the Tetum word for “together” for helping Timor achieve liberation and reeled off some remarkable achievements.

The tiny country now had the region’s strongest democracy, rated higher on the Freedom House index than Australia and US for free media, and had raised life expectancy from less than 60 years before independence to 70 years today. It had no political violence or organised crime – “we are too disorganised for that”, he quipped – before cracking a few jokes about John Howard and Australia’s convict past.

A visitor to Australia is pulled out of line on his way into the country and asked if he has a criminal record. “I didn’t realise that was still a requirement,” the visitor responds.

The crowd laughs along with the President.

Australians have an incredible sense of humour, Mr Ramos-Horta told his guests in a warm and easy monologue that by turns poked and flattered. But its government was unnecessarily paranoid about China’s presence in the region, he said.

Australia and Portugal were Timor’s main security partners, he assured, brushing away concerns over Dili’s Comprehensive Strategic Partnership with Beijing last year that committed both nations to closer security ties.

Yet Australia and the US have watched with alarm as China has moved to build security partnerships across the region, following a 2022 agreement with Solomon Islands allowing for the deployment of Chinese “armed police, military personnel and other law enforcement forces” there.

The Albanese government scored a win last month when Pacific Island leaders unanimously endorsed a $400m regional policing plan to improve training and create a multinational crisis reaction force. Two weeks later, China opened a facility for training Pacific police in Fuzhou.

Mr Ramos-Horta says Australia need not fear China’s presence in Timor – a tiny nation with outsized strategic importance due to its location at the crossroads of Southeast Asia and Oceania – and that Beijing only wants to help grow its economy.

The two countries signed agreements on an array of economic projects during his state visit to Beijing in July, where he and President Xi Jinping again committed to “enhance exchanges at all levels between the military and police forces”, through training and joint exercises.

Mr Ramos-Horta is a strong defender of China and its One China policy which asserts ownership of Taiwan, and earlier this year called for a freeze on arms sales to Taipei. He told The Australian Beijing wanted the South China Sea to be a “sea of peace and co-operation” – notwithstanding its relentless aggression against smaller neighbours.

China’s current aid to Timor – at just $5m a year a fraction of Australia’s $150m aid spend – would hardly seem to justify such spirited defence, though China’s infrastructure contributions, from the new Tibar Port to the presidential palace, are certainly more visible than Australia’s work on health, education and capacity building.

The problem with Western countries is they “wait for perfection”, he mused. So much of Australia’s aid went to study after study, whereas China mucks right in and gets things done.

Mr Ramos-Horta has great hopes for what Beijing can do for his country. His son Loro, Timor’s current ambassador to China, recently brought over a delegation of senior Chinese executives representing 300 companies. Another delegation is due next month.

“The Australian media often talks about Chinese influence in Timor-Leste. There are more Chinese in Australia than in Timor Leste,” he tells the Interfet crowd, who look slightly bemused at how the conversation has turned.

It is the Timorese that should be worried about Chinese influence in Australia, he says citing the 100-year lease of Darwin Port to Chinese-owned Landbridge.

Canberra would “go berserk if we did that”.

No white knight

While the prevailing Australian view of our role in East Timor is that of a white knight that protected the people when Indonesian troops ransacked the country on the way out, Dili’s resistance-era leaders have a more unvarnished view of Canberra’s legacy.

Mr Ramos-Horta is careful to draw a distinction between the Australian people – “true friends” to East Timor – and their government that backed Indonesia’s 1975 annexation of East Timor after Portugal ceded colonial rule.

Rui Maria de Araujo, Timorese prime minister between 2015 and 2017, says there is “mutual mistrust” and unhealed wounds dating back to World War II, when Australian troops “occupied” Portuguese East Timor.

Western concerns over China’s creeping influence are seen as paternalistic in Dili where no one needs reminding of the price the Timorese had to pay for their sovereignty. Yet across the country, there is growing resentment at the explosion of Chinese-owned businesses, from convenience stores to supermarkets and service stations and even farm land.

In some areas, like the South Coast village of Suai, there is now active resistance to more Chinese businesses and farmers coming in, says Nelson Belo of Fundasaun Mahein, an NGO that analyses security challenges.

“It’s a time bomb and one day it’s going to explode. It’s a big disagreement between the people and their leaders.”

Joaquim da Fonseca, a former ambassador to the UN and UK, says playing the “China card” is a high-risk gamble for the government that could blow up in its face.

“They (China) have just built the presidential palace, foreign ministry office, ministry of defence and so on. It would be stupid to think this is for free. There will be a time when Chinese companies turn up on our door and want this project or that project, this contract or that. ”

Like others, he worries the government is relying too heavily on Greater Sunrise to solve its problems. “We don’t know if production will come on stream early enough to fend off bankruptcy. Most political leaders do not accept this as a possibility but we have a very good chance of becoming a failed state if things do not improve swiftly,” he says.

It is a scenario that surely keeps Australian political leaders up at night. Australia wants a good relationship with East Timor and does not want it to be a failed state, says Deakin’s Professor Kingsbury.

“If that happens, China is not going to be its saviour. They will look at East Timor and say ‘what’s in it for us?’ ”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout