Drones cast air of death over Syria repatriation

The mission to repatriate Australian women and children from the detention camps in northeast Syria will require a delicate operation in one of the most dangerous parts of the world.

The mission to repatriate Australian women and children from the detention camps in northeast Syria will require a delicate operation in one of the most dangerous parts of the world.

As well as an ongoing dangers posed by Islamic State sleeper cells, a relatively new threat in the region is the escalation of a bombing campaign by Syria’s large northern neighbour, Turkey, which has been using drone strikes to devastating effect along the border regions.

The al-Roj detention camp where the cohort of 58 Australians is being housed is in the safest part of northeastern Syria, close to the Iraqi border, but well within reach of Turkish artillery.

The Iranians have also been known to send missiles into the region, targeting US military assets, mainly around Hasakah and Deir ez-Zor, several hours from al-Roj.

The increasing use of drones and the rising civilian death toll have caused further instability in the region, as the Syrian Democratic Forces, tasked with guarding the camps and prisons holding Islamic State members and their families, are distracted by the military campaign by Turkey.

Caught in the middle are the civilians, including children, who have been victims of the drone strikes.

Ahing Hussein loved his job as a mechanic. On a Tuesday afternoon in August, the 14-year-old took a photo of his oil-stained hand clutching two spanners. Shortly afterwards, Ahing and his 16-year-old cousin, Ahmad, who was working alongside him, were killed just outside their workshop.

His family found the photo later on his mobile phone. The phone survived the laser-guided missile fired by a Turkish drone. Ahing, Ahmad, and three other men did not.

The boys’ story is a tragedy, and one becoming increasingly familiar in northeastern Syria, as Turkey turns to a game-changing new weapon in its decades-long fight with the independence militia known as the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) and its Syrian offshoot, the YPG – the Bayraktar TB2 drone.

While the targets of the strikes are military leaders, many of the victims are civilians, including children, like the five girls killed on a volleyball court on August 18 at a UN-sponsored girls school outside Hasakah. Like Ahing and Ahmad.

“A bad dream has happened to us,’’ said Masoud Hussein, 19, brother to Ahmad and cousin to Ahing. He had finished his shift at the family workshop a few hours earlier but was in the neighbourhood collecting dinner for his father, Ali, when the drone struck.

“On my way back I saw a big smoke in this area. I was afraid my father was there. The traffic was stopped and all streets were closed because of what happened. I went closer and I saw my father’s car.

“Many people were around my father’s car. Then I knew. I screamed and asked them to take me to my father. When I arrived I didn’t see him, so they had taken him to hospital. I went there (to the hospital), I saw my father was injured.

“I didn’t know that my brother was with him and something had happened to him. Or my cousin. I didn’t imagine they were in that attack.

“I went to kiss his hand, they told me he was fine. I went to confirm and then in a sad way he (father Ali) told me, ‘go and see your brother, he is dead. I cannot see him, go to see him. He died in the attack’.

“I didn’t believe it had happened with my brother. I went closer and I saw my brother was in the bed near my father, next to my father.

“I came closer to him and they put a blanket over him. I took off the blanket from his face and I saw my brother had died. I passed out.’’

While Ahing and Ahmad’s deaths went unnoticed in the international community, the rising civilian death toll in the region is causing concern among security partners.

According to the Syrian Democratic Forces, the quasi-official Kurdish army in the region, 34 people were killed and 46 wounded in strikes by Turkish drones, artillery and tanks in August alone. Of those killed, the SDF said 17 were civilians, including children. Of the wounded, 35 were civilians.

The US, which backed the SDF in the war against Islamic State, has issued two statements condemning the attacks but not mentioned its NATO partner Turkey by name.

Drone dilemma

The deployment of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), or armed drones, has brought a new menace to a war-weary region still recovering from the fight against Islamic State, which ended just three years ago.

The Bayraktar drones are built by a company named Baykar Technology, owned by two brothers. One of them, Selcuk Bayraktar, is Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s son-in-law.

The low-cost, slow-flying UAVs were dubbed the “Toyota Corolla of drones’’ by American military expert Aaron Stein, director of research at the Foreign Policy Research Institute, who told CBS in March the Bayraktar “doesn’t do everything that your high-end sports car does, but it does 80 per cent of that”.

Costing just $US5m each, the medium-altitude drones, which have a 3.5m wingspan and are armed with four laser-guided micro missiles, gained an international profile when Baykar donated three to the war effort in Ukraine against Russia.

They were specifically designed with the war against the PKK in mind and, after a first mission eight years ago, the drones have now racked up 500,000 hours of flying time. Selcuk Bayraktar says the company now has procurement orders from 24 countries – despite a three-year waiting list.

And, while crowd-funding efforts to buy the drones to help Ukraine have proved hugely popular, it has gone mostly unnoticed that they are being deployed across northeastern Syria as part of Turkey’s targeting of the senior leadership of the PKK (which is proscribed as a terrorist organisation in Australia, the US, Turkey and Europe) and the YPG.

The drones, whose lights can be seen flying across the northern Syrian cities of Qamishli, Idlib and Kobani at night, have proved effective against key military targets – and devastating for the civilians unlucky enough to be in the vicinity when they strike.

Twist of fate

Ahing and Ahmad were not military figures, and simply had the bad luck to be called in to repair a car carrying a Kurdish independence figure known as Youssef Mahmoud Rabbani, an Iranian leader of the PJAK (Free Life Party) visiting Syria on August 6.

The drone strike at 6.30pm in the al-Sina’a district – a light-industrial and residential area in the eastern part of the border city of Qamishli – killed Rabbani, his driver, an associate who helped them get their car fixed, and the Hussein boys.

The Hussein family are more usually known as Shebi, from the village they grew up in. Several generations of their men worked in their little car repair shop in al-Sina’a. Ali and Akram Hussein-Shebi are cousins, but their sons, Ahmad and Ahing, grew up together and are considered cousins too.

The family have been going over the events of August 6, trying to work out how the boys became targets. It appears that when Rabbani’s car developed a fault, his driver called someone he knew, who worked for the SDF. The SDF man knew Ali Hussein was a mechanic, but when he couldn’t reach him on the phone, he called Ahmad. Ahmad was home with his dad, so the pair got on their motorbike and went to the shop, calling Ahing along the way.

Father’s horror

Ali remembers little of the drone strike, apart from the pain as shrapnel ripped into his body, disembowelling him, burning the skin from his face, and breaking his arm. He doesn’t know how many pieces of shrapnel remain in his body – there are 47 in his right leg alone. He remembers his son’s mutilated body lying next to him.

Speaking from his hospital bed just three days after the attack, Ali, a bucket of bloodstained bandages still under the bed beneath him, wept as he told how his soccer-loving son and their cousin came to be at the car yard.

It was 45 degrees and, like most residents of Qamishli, which has limited electricity, they had gone home to wait out the heat of the afternoon.

“We went home early to our house because it was so hot, before 6.30, then someone called to say they needed something at the shop and I came with my son to the shop,’’ Ali aid.

He thinks the drone attack happened five minutes after they arrived, but it’s likely it was later, when Rabbani was sitting in the vehicle outside the shop, along with his driver. The SDF man was leaning in the car window talking to them. Ahing and Ahmad were a few steps away.

“He was six years old when he started to work with me. He tried to learn to fix the cars since he was six,’’ he said of Ahmad.

“When the attack happened … when the drone attacked I passed out, then I felt the shots (shrapnel wounds) in my body. My son was next to me. On this side, on his face and his side. I started to sing so I would not pass away.’’

‘Defend our people ’

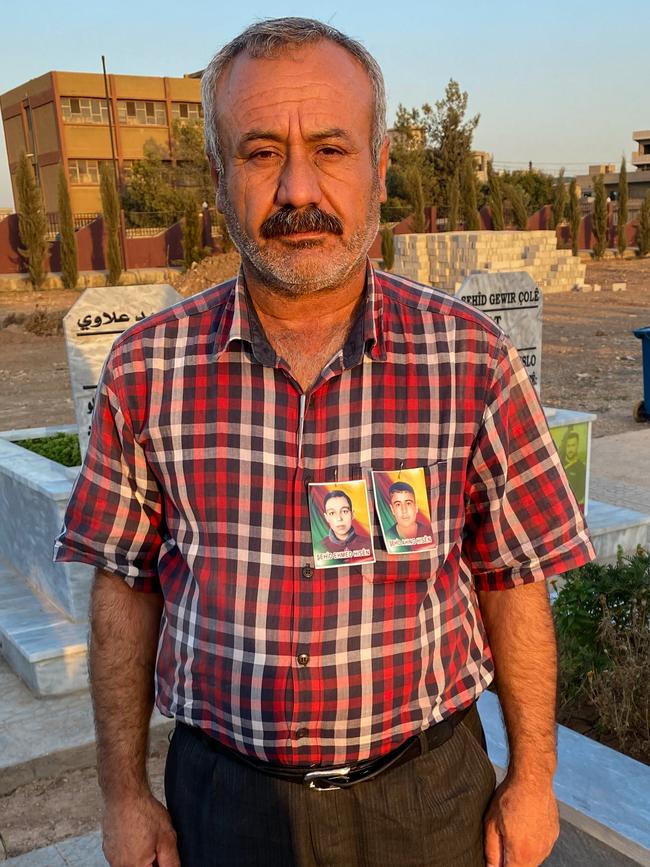

The boys’ family invited The Australian to spend time with them at their sons’ gravesite in Dalil Sero’khan, the Martyrs’ Cemetery in central Qamishli.

Ahing’s father, Akram, said he never expected such a tragedy to befall their family.

“I just wanted my son to learn this career and then open his own shop. He was studying in the winter and in summer he was working with his cousins,’’ he said, a photograph of both boys pinned to his shirt.

“Even (Ahing’s) teachers when they heard about it, they came here and they were so sorry because at school he was so good, so clever and smart,

“He had the good ethics, with his friends and his teachers.

“He was a good keeper in football, he dreamt one day he would be famous

“I know it’s so difficult for us as a family but he’s not more important than these people either,’’ he said, waving his hand at the hundreds of other headstones in the Martyrs’ Cemetery, all victims of northeastern Syria’s endless war.

“I consider us like the rest of the martyrs here.’’

SDF spokesman Aram Hanna said the northeastern area of Syria was home to a diverse range of people including Kurdish populations, Sunni Arabs, Christians, Syriacs and Assyrians.

He accused Turkey of striking churches, mosques, schools and civilian neighbourhoods, not just military targets. “Here in Qamishli until Derik (a town 100km away) there were more attacks coming in the last three or four days especially with the air strikes of the drones,’’ he said.

“It is clear for us and for the public opinion too that they are targeting the people who defeated ISIS, and the leaders who are trying to plan every day to defeat ISIS and to provide safety for north and east Syria.’’

The SDF responded with an artillery strike across the border in August that killed seven Turkish soldiers in an armoured vehicle in Mardin. The move infuriated the Turks, who responded with a renewed aerial bombardment.

Mr Hanna insisted the SDF was not an offensive force but a defensive one, and the shot across the border was in northeast Syria’s defence, to “ensure the safety of all people and the safety of our region”.

“Our forces are national forces, our people are Syrians, Kurdish Syrians, Arab Syrians, we have the right to defend our people and we have all the rights to defend the sacrifices our comrades gave for the freedom of our people and the safety of all of us,’’ he said.

“We didn’t attacks the Turkish lands, we responded with a series of military operations.’’

Turks ‘are like ISIS’

Mr Hanna said the Bayraktar drones were built in Turkey from components sourced from countries including Germany and others in the European Union.

“They are (also) using suicide drones, which are exploding and make a really big effect on our citizens and civilians,’’ he said.

“It’s a complete explosion, it’s no different from the suicide cars and what ISIS did in Qamishli back in 2014, 2015. ISIS always tried to attack our area by such like these attacks, and the Turks are repeating that. They are attacking the people ISIS couldn’t reach.’’

Mr Hanna said the action from Turkey was distracting the SDF in its fight against Islamic State, and was coming at the same time as the SDF was conducting joint operations with the US-led coalition.

“Unfortunately we don’t call any (international) governments anymore, we lost hope from any of them,’’ he said. “(Instead) today we call on the people, the European people, the Australian people, to move and to play their role in a positive way that supports our efforts with all things that we do. Such like defeating ISIS and providing safety for our people.

“We have thousands of ISIS jailed in arresting places (prisons) and we have the camps too.

“It’s enough for us to think how to deal with them, we don’t need any other things that (affect) our efforts in this aspect.’’

Mr Hanna said hundreds of civilians, including children, women and the elderly, had been killed or wounded by Turkish artillery and drone strikes since 2019.

“We call on the international community to play its role better and see what is happening here in north and eastern Syria. To see the fights and see the attacks and the result of it and to stop it.’’

The Turkish embassy in Canberra did not respond to requests for comment.

Politics for Erdogan

Lowy Institute Middle East expert Rodger Shanahan said Mr Erdogan was looking at a military operation to push Kurdish fighters 30km from Turkey’s border.

He said this was part of the ongoing security concerns Turkey held about the YPG, the Syrian branch of the Iraq-based PKK, which had been waging war with Turkey for decades as part of its push for an independent Kurdistan across parts of Syria, Iran, Turkey and Iraq. The PKK had committed atrocities in Turkey, including bombings in civilian areas, and is reviled among many Turkish civilians, as well as by the military and political elite.

“Another aspect of it is to have a zone of influence potentially along the entirety of their (Turkey’s) southern border into Syria,’’ Dr Shanahan said.

“The third aspect is potentially, having established that kind of security zone, being able to relocate or encourage some of the millions of Syrian refugees still in Turkey to return to northern Syria.’’

More than 3.5 million Syrian refugees have sought refuge in Turkey, and Mr Erdogan is seeking to return a large number of them to Syria. They are likely to be resettled in Kurdish lands around Afrin and Idlib, which Turkey essentially controls – despite many being Syrian Arabs from the country’s south.

“The political background over all of this is President Erdogan in Turkey is facing an election next year, the economy is not going well, so the issue of Syrian refugees in Turkey is more pronounced than it has been before,’’ Dr Shanahan said.

“There’s certainly domestic political pressure in Turkey, given the way the economy has gone … there’s that sense of enough is enough, and some of the political parties are using that as a political tool against Erdogan. The other issue is certainly changing the demographics and reducing the Kurdish population along the southern border, replacing it with a Sunni Arab population, that would certainly be a calculation among the Turks as well.’’

‘We are human also’

The war in Ukraine, which has distracted Russia, also gave Turkey an opportunity to assert its power in Syria.

Dr Shanahan said the US would have been cautious in criticism of Turkey partly because of their shared NATO membership.

“The US also needs Turkey onside to admit Sweden and Finland as new NATO members, so they have to be pretty careful with the diplomatic dance that they’re dealing with,’’ he said.

The diplomatic dance means little to the grieving families of Ahing and Ahmad Hussein. Ahing’s sister, Torin, said the boys were close friends as well as cousins and workmates, and “wherever they went, they went together”.

“We as families … have this pain and … sorrow. We hope that when time passes it will become better but we are suffering a lot. When we see anything related to the boys, their clothes, their things at home, we remember them,’’ she said.

Miss Hussein urged the international community to consider the rights of Kurdish civilians to live in safety and peace.

“The countries that pretend they are protecting the human rights – where is the human rights in this case? Where is the rights for children, where is it?

“They are killing our children, and no one talks about it.

“We call on the community to intervene, to do something, for we are human here also.’’