Coronavirus: States prepare for $1.6bn debt bill

The interest bill on the debt held by the states and territories will soar by $1.6bn a year as they borrow heavily to beat COVID-19.

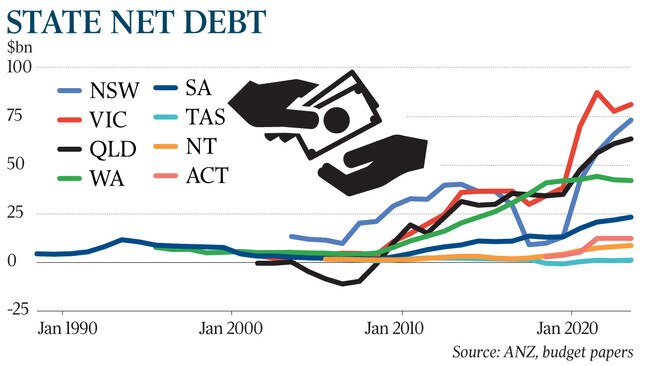

The interest bill on the debt held by the states and territories will soar by $1.6bn a year as they borrow heavily to beat COVID-19 and double their net debt loads.

Borrowings by states and territories are estimated to rise to $290bn by June next year from $150bn last June as states move to keep their economies alive.

The states have promised $50bn in fiscal stimulus to offset the damage from the COVID-19 crisis, adding to already hefty infrastructure commitments.

NSW’s net debt will more than quadruple, from $13bn to $56bn, before expanding to $73bn by June 2023.

Over the two financial years to June 2021, Victoria’s net debt will surge from $38.3bn to $87.2bn, after committing to an extra $30bn in COVID-19-related support measures over this financial year and the next.

Queensland’s net debt will climb by 60 per cent by June 2021 to $56.2bn from $35bn.

Governments at all levels have delayed budget documents as they deal with the unprecedented shock from the worst pandemic since the Spanish flu more than 100 years ago. But it is possible to estimate the bulging net debt profiles of the states and territories by using the latest budget papers and adding in emergency stimulus commitments announced in recent weeks, as measured by ANZ.

The calculations also make small adjustments for the hit to revenues from the collapse in economic activity.

Net debt across states and territories will nearly double by the end of next financial year, from $148bn in June 2019, to $286bn by June 2021, and $305bn by June 2023. Assuming an interest rate of 1 per cent, servicing the extra borrowing will add $1.57bn to the total interest bill.

While she said it was “very difficult” to put together long-term historical state-level data, ANZ senior economist Cherelle Murphy was confident that “we now have more debt across the states than probably ever before”.

“We are looking at really historical highs,” Ms Murphy said.

State economies had already been experiencing a “challenging” period before the summer’s disastrous bushfire season and the arrival of the coronavirus, Moody’s senior credit officer John Manning said.

That had undermined states’ economic fundamentals, which meant “a lot of growth had been underpinned by state infrastructure spending”.

And while the funding task facing the states now looms even larger, Mr Manning said they were at least having no trouble borrowing the money they need.

“Access to global funding markets since the start of March has been very strong,” he said. The Reserve Bank’s bond-buying program has offered a ready source of demand for state debt in the secondary market and lowered borrowing costs to less than 1 per cent.

Still, finding a way to pay down the debt, despite historically cheap interest rates, will loom as a political and financial issue once the immediate crisis has passed.

And raising money through the sale of public assets will not be easy, S&P Global Ratings director of sovereign ratings Anthony Walker said. “Victoria is rapidly running out of room to recycle assets,” Mr Walker said.

NSW is in the very early stages of selling off the other half of the WestConnex motorway in Sydney, which could raise $10bn, but there were no other major contenders, he said.

Queensland has plenty of public assets, but little public appetite to sell them, complicating that state’s task.

In early April, S&P affirmed the AAA ratings on the Australian commonwealth and AAA-rated states NSW and Victoria, and on the ACT, but revised its rating outlooks to negative.

Despite the hit to budgets and ballooning debt levels, Mr Manning said his ratings agency was relatively sanguine that states and territories would come out the other side in reasonable condition.

“The coronavirus and its impact on economic conditions will weaken states’ financial metrics, but we don’t think it will damage them permanently,” he said.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout