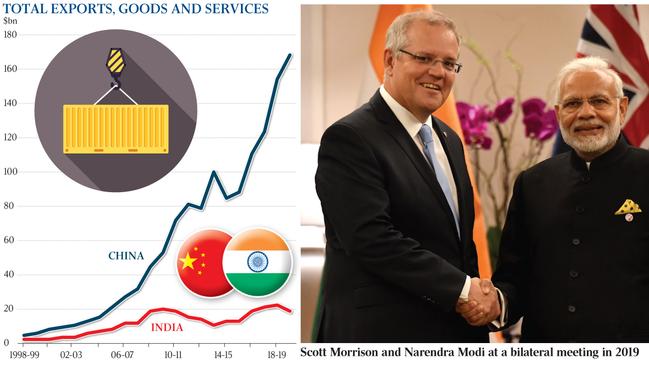

China row opens export opportunities for India

India moves to fill the Chinese vacuum for resources and wine, as a free-trade agreement between Canberra and New Delhi gains momentum.

India is moving to fill the Chinese vacuum for Australian resources and wine, as a free-trade agreement between Canberra and New Delhi gains momentum under a Morrison government push to unlock new markets.

The Australian understands Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi is eyeing off greater access to Australian resources, including coal and rare earths, ahead of Adani’s Carmichael mine in Queensland producing its first coal load this year.

As part of India’s COVID-19 economic response, the Modi government has eased mining regulations to attract foreign investment in India and permitted the commercial mining of coal. There is also a push to access Australian coal, iron ore, copper, steel aluminium, cobalt, rare earths and nickel.

Companies including Coal India Limited are actively engaging with the Australian miners. The Confederation of Indian Industry’s Australia economic strategy is encouraging Indian companies to invest in exploration and mining of key minerals such as coal, iron ore and critical minerals.

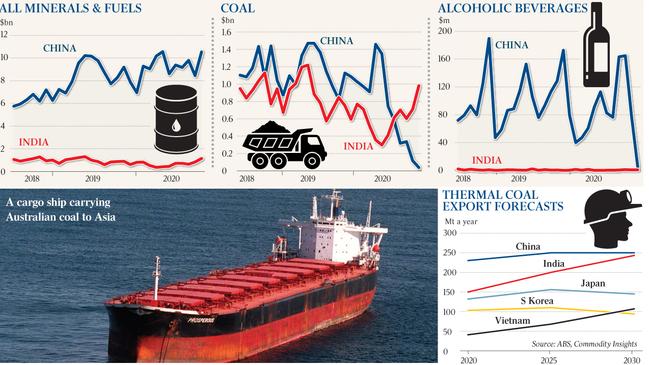

Bravus Mining and Resource chief executive David Boshoff, who took control of the rebadged Adani Australia last July, said the company had “secured the market for 10 million tonnes” a year from the central Queensland mine. “The demand for thermal electricity is still growing in India and Southeast Asia and both coal and renewables are needed to provide safe, affordable and reliable power,” Mr Boshoff said.

“Furthermore, due to the high quality of our coal and the low strip ratio, Carmichael coal is in the lowest-cost quartile, which means the economics are good and we can be profitable through the cycles. The coal will be sold at index pricing and we will not be engaging in transfer pricing practices, which means that all of our taxes and royalties will be paid here in Australia.”

Scott Morrison, who was forced twice last year to delay official visits to India, regularly speaks with Mr Modi, including last month. The Australian understands that while India’s protectionist policies and tariffs on Australian resources and wine remain a hurdle, there is growing optimism a deal could be reached.

Trade Minister Dan Tehan said that, although patience would be required in working with the Indian bureaucracy, there was significant “willingness” to strike a deal, first floated during the Abbott government.

“There’s a solid foundation of will and really wanting to cement the advancements that have been made in the economic relationship,” Mr Tehan said.

He said the government would consider early harvest agreements, addressing concerns on both sides around agriculture, as well as unlocking opportunities for miners after China banned Australian coal.

“We want to get a very constructive dialogue happening, one which puts ambition back into the free trade agreement,” he said.

The government has commissioned analysis showing how a deal could work in India’s interests. “Investment flows are something that India are very keen on, so how we can … encourage Australian investment into India is going to be a key to unlocking progress on the deal,” Mr Tehan said.

He said the government was looking at ways for wine exporters, hit by China’s trade restrictions, to get into the Indian market.

“The biggest issue there is that there is a 150 per cent tariff,” he said. “But obviously any discussions we would be looking at seeing what we could do there.

“Whether we could look at ways where you could potentially seek tariff reductions for wine valued over Australian $25 or $30 — that way you work with India so they can continue develop their own wine industry but at the same time help and support our exporters get into the market.”

Australia India Business Council national chairman Jim Varghese expressed optimism for a bilateral agreement that “meets a much bigger focus”, with opportunities across agriculture, health, education and training, digital economy and defence.

“The China nexus at the moment, I think, would encourage that,” Mr Varghese said. “We’re looking at supply chains a lot more, largely as a result of the China conflict we have at the moment. What we see now is increased activity in bilateral trade across sectors. I think the pressure for a free-trade agreement will build up.”

Mr Varghese — whose brother Peter is the University of Queensland chancellor, a former DFAT secretary and author of the India-Australia economic strategy — said Mr Modi would not drop the “economic reform ball” but faced domestic challenges, particularly in agriculture. He said he was contacted by two wine suppliers last week asking if AIBC could help connect them with the Indian market.

“The Indian drinking habits are starting to embrace wine in areas where you can drink it,” he said. “There’s also a large domestic market. I do believe that there is an opportunity to explore the wine market.”

Confederation of Indian Industry chief representative Abhay Mehta said India’s decision not to participate in the regional comprehensive economic partnership last year, despite Australia’s urging, had shifted the focus towards New Delhi and Canberra securing a two-way agreement.

Queensland Nationals senator Matt Canavan, who strongly backed the Adani coalmine before the 2019 election, said that even if China did not take another tonne of coal from Australia, the growth in India’s coal demands would be greater than Australia’s previous coal exports to China.

Senator Canavan, who visited the Carmichael mine on Thursday, said the International Energy Agency had forecast that India’s coal demands would grow over the next 10 years by an amount that is more than half of Australia’s total coal production.

“Even before China’s coal ban, it was clear that India was a massive growth opportunity for Australian coal,” Senator Canavan said.

“After China’s coal ban, it becomes more important that we seek to negotiate a trade agreement that puts Aussie coal on a level playing field with Indonesian coal in the Indian market.”

With India having a geology similar to Western Australia and untapped resources potential, Mr Varghese said there were significant opportunities for the Australian mining equipment, technology and services industry to support India’s burgeoning resources and rare earths sectors.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout