China diaspora: Dissident delivers cautionary tale of China’s ingratitude

Former political prisoner Jin Cheng has a warning for Australia from an ancient Chinese fable, Mr Dongguo and the Zhongshan Wolf.

Former political prisoner Jin Cheng has a warning for Australia from an ancient Chinese fable, Mr Dongguo and the Zhongshan Wolf.

The fable, written more than 1000 years ago, is a morality tale about ingratitude.

Mr Jin says the story cautions how China might act after being helped to economic riches by the West.

In the fable a scholar, Mr Dongguo, lets a wolf hide in his bag to escape hunters. Once saved, however, the wolf tells the scholar that he must now let the wolf eat him because he is hungry.

When Mr Dongguo protests the wolf’s ingratitude, the pair decide to present their case to the judgment of three elders.

An old farmer tricks the wolf into getting back into the scholar’s bag and beats it to death.

The term Mr Dongguo has become a Chinese idiom for a naive person who gets into trouble through being soft-hearted towards evil people.

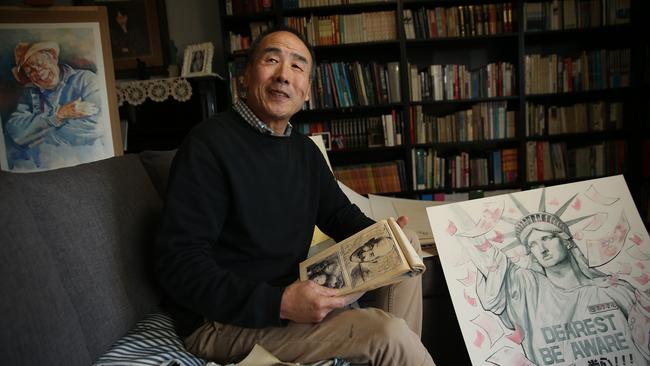

A cartoonist, Mr Jin was granted asylum in Australia after being jailed in Beijing following the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989.

His family already held a deep-rooted antipathy towards the Communist Party — in 1949, two of Mr Jin’s uncles, who were working in banking and finance for the national government, were executed by the communists during a crackdown on anti-revolutionaries.

Mr Jin was working as a teacher when the democracy movement swept up students in Beijing in 1989. “I was a teacher so I joined with the students,” the 62-year-old says.

He rejects the Communist Party’s attempts to downplay the upheaval in Tiananmen Square as an “incident” rather than a “massacre”.

“I am a witness and a survivor,” Mr Jin says. “It was a massacre.”

After the killings in Tiananmen Square, Mr Jin became an illustrator for an underground magazine called The Bell which was created to tell the truth about what happened in 1989.

He was sentenced to jail for a cover illustration that offended the communist censors.

“At that time I was just an ordinary person and did not know much about politics,” he says.

Released from prison after a year and a half, Mr Jin was banned from travel for 18 months.

When Australia relaxed its tourist visas in 2004, Mr Jin came as a tourist and applied for political asylum, which was granted.

Two days after applying for asylum, Mr Jin says he was visited by two staff members from the Chinese embassy, who told him to “shut up”.

“I was really shocked that they found us so quickly,” he says.

Mr Jin still cries with emotion at the protection he has received in his adopted country.

“Australia is a Noah’s ark for me,” Mr Jin says. Working in construction, Mr Jin, says he has never collected any welfare benefits from his new home.

“When I came here (Australia) I read a book called 1984 and it is the same as life in China,” he says.

Mr Jin is critical of Chinese people who don’t make a greater effort to assimilate when they migrate to Australia.

“I do not understand why those who migrate to Australia do not recognise the value of Australia and do not love this country,” he says.

“If you don’t like this country why don’t you return to your own mother country?”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout