Business Council of Australia migration warning to hit home

The national failure to free up housing supply must not be used as a ‘scapegoat’ to reduce the migrant intake, warns the Business Council of Australia.

The national failure to free up housing supply must not be used as a “scapegoat” to reduce the migrant intake, amid escalating global competition for talent and a political deadlock over Anthony Albanese’s $10bn housing package.

The warning from the Business Council of Australia, in a paper on migration reform, comes ahead of a crucial meeting of state and federal leaders next week at which the Albanese government is hoping to advance a deal to strengthen renters’ rights and increase housing supply.

In the paper to be released on Thursday, the BCA says the current system needs to be reformed because Australia is “competing against other countries for the best and brightest” and that “slow or complex migration systems … put the nation at a disadvantage”.

The paper rejects the narrative that Labor is pursuing a “big Australia” policy as a myth, arguing that “migration should not be the scapegoat for poor planning and the failure to deliver housing supply”.

Property groups on Tuesday warned that the wave of post-pandemic migration, while welcome, was putting extra pressure on infrastructure and housing.

They said the nation was not on track to meet Labor’s target of building an extra one million homes by 2029.

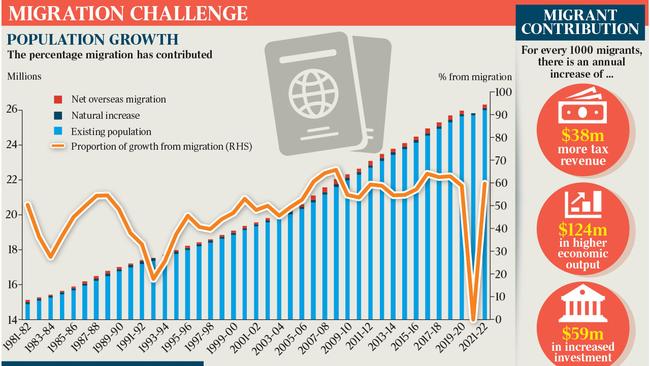

While the budget forecast net overseas migration in 2022-23 at 400,000 and 315,000 in 2023-24, the BCA said the population was now estimated to be more than 375,000 people below the pre-pandemic forecast. By the end of the decade, it was “still expected to be 225,000 short of the pre-pandemic projection”.

The Prime Minister told parliament that freeing up housing supply would make the “big difference” in meeting the extra million homes target, and states and territories would need to implement their own plans.

“Now that’s about land release, it’s about zoning, it’s about density, particularly around appropriate public transport routes, and it is about making sure that we increase supply,” Mr Albanese said. “Because that is what will make the big difference. I’m confident that next week we will have some really good outcomes and results.”

The Coalition has accused Labor of having no plan to deal with a surge in net overseas migration, arguing the increase was putting pressure on housing, rents and hospital waiting lists.

Greens housing spokesman Max Chandler-Mather signalled on Tuesday that the outcome of the national cabinet meeting could influence negotiations over the passage of Labor’s stalled $10bn Housing Australia Future Fund in the Senate.

The Greens are blocking the passage of legislation, demanding Labor invest up to $2.5bn each year in affordable housing and provide a further $1bn to entice the states and territories into implementing a two-year freeze on rental increases. “It is increasingly untenable for the government not to do anything on rents,” Mr Chandler-Mather said.

“We have forced national cabinet to at least start to talk about it. Now what we want is action out of it. If action comes out of it, of course we are willing to look at those details and consider our support for the Housing Australia Future Fund.”

The chances of securing a rent freeze from next week’s national cabinet meeting appeared doomed on Wednesday after key Labor states – including Western Australia and NSW – reaffirmed their opposition to the demand made by the Greens.

Speaking on Wednesday, WA Premier Roger Cook said he supported Mr Albanese’s “push to increase the availability of housing” but ruled out entertaining the introduction of a rent freeze.

“That’s not part of our reform package,” Mr Cook said.

“We’ve already (provided a) significant amount of funding with regards to the availability and supply of housing.”

A NSW government spokesman reaffirmed that Premier Chris Minns was “not considering a rent freeze”, although a discussion on improving housing affordability was welcome.

However, Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews said he thought there was more that could be done to strengthen the rights of renters.

“To the extent that other governments are interested in following Victoria’s lead, I’m more than happy to brief them, more than happy to share ideas on how to better protect renters, but also to give to landlords certainty,” he said.

Mr Andrews in July revealed that a two-year rent freeze – with caps on increases – was among options his government was considering, saying “everything” was “on the table”.

Property Council of Australia chief executive Mike Zorbas said that for Labor to meet the target of building one million extra homes by 2029, it would have to make state governments accountable for housing targets.

Housing Industry Association deputy managing director Jocelyn Martin also said it was possible to meet the target but there had never been five consecutive years in which 200,000 homes had been built.

“Looking at the trends at the moment, it’s not going in the right direction to do that,” Ms Martin said.

Master Builders Australia chief executive Denita Wawn said Australia was facing critical worker shortages across multiple sectors, but the government faced a major challenge to provide an estimated 557,000 dwellings by 2024-25 to house a growing population.

“Government action therefore in migration and housing policy needs to be working together to resolve the challenges of a bigger population,” Ms Wawn said.

“This will be difficult to achieve while inflationary, workforce and interest rate pressures are constraining building activity and construction business viability.”

Judo Bank economic adviser Warren Hogan said the Albanese government’s decision to accelerate migration so the population caught up to the pre-pandemic trend was one of the “most profound policy decisions” of the year.

“I think it was a very risky policy both in terms of the housing position and the industry challenges of delivering housing supply without a population surge,” Mr Hogan said.

“And, of course, there’s also the issue that is frustrating the RBA’s efforts to slow the economy … There’s a reason they did it, but I don’t think they considered the challenges enough.”

Economist Saul Eslake said although migration was playing a role in the housing crisis, it was not the fundamental cause.

Mr Eslake said the crisis was caused by a failure of all levels of government to build new housing supply, which had been exacerbated by tough economic conditions for builders, including high labour and material costs.

“The very high level of migration we’re seeing at the moment is catching up from when there was no migration at all because the borders were closed during Covid,” Mr Eslake said.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout