That reeks of complacency but, to quote Donald Trump, “it is what it is”. When big spending takes centre stage, and the Treasury says “relax, just do it”, budget repair can wait for another day.

In a season of cheap money, all the political signals say buy now, pay later.

The Treasurer’s two-phase fiscal strategy is clear. First, lock in a strong recovery through high spending to cut unemployment to pre-pandemic levels or lower. Second, transition to a medium-term goal of stabilising and then reducing gross and net debt as a share of the economy.

Easy, right? Independent observers believe the strategy is “affordable” and the debt is “sustainable”. Partisans are calling it a debt tunnel of doom.

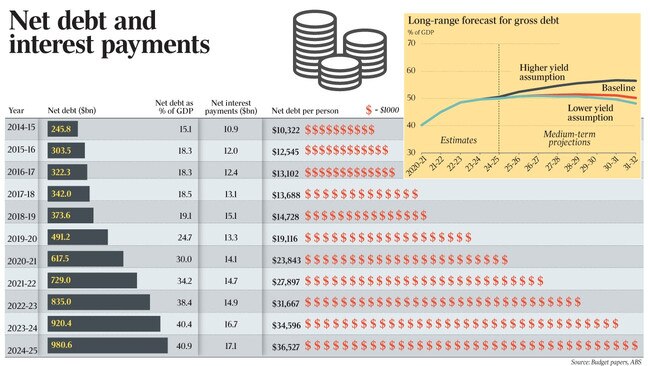

Treasury expects gross debt to hit $1.2 trillion by the end of its four-year forecasting period, or 50 per cent of gross domestic product, and to stay there until 2031. This is the highest level since World War II, according to the independent Parliamentary Budget Office.

Taking into account the government’s assets, net debt will peak at $981bn in June 2025, or 40.9 per cent of GDP, and seven years later will drift down to 37 per cent. Before the Treasurer’s latest spending extravaganza, the PBO calculated it would take until 2055 before debt returned to its pre-COVID level of 30 per cent of GDP.

There are a few things running in Frydenberg’s favour on debt, not least of which are low borrowing rates and an ultraconservative budget forecast of an iron ore price of $US55 a tonne. On Wednesday, the Treasurer told the National Press Club the strategy was not hostage to sky-high prices, now running at above $US200 a tonne. He said tax revenue would be $12.5bn higher over two years if iron ore remained above $US150 a tonne until March.

“We can also move forward with confidence, knowing that our fiscal projections are not beholden to volatile commodity prices,” Frydenberg said. He claimed his cautious approach protects the budget “by not baking in future spending against a record high iron ore price”.

Not everyone agrees. The structural budget position will deteriorate, courtesy of new social spending that lives on way beyond the COVID-19 crisis. What goes into the budget rarely comes out.

Compared to the October budget, the outlook for net debt, which the Treasurer says is a measure of fiscal sustainability, is projected to be lower each and every year over the coming decade.

The ratings agencies have mixed views on our medium-term position. According to Anthony Walker of S&P Global Ratings, “downside risks remain, underpinning our negative outlook on Australia”. Walker sees less room to borrow at the AAA-rating level because budget repair could take longer than expected and the stock of debt will remain elevated for years.

Other analysts believe little has changed and budget repair, when it does come, is likely to be a moderate affair rather than a scorched-earth consolidation. Austerity is the bogey word to slam debt doomsayers.

The Treasurer points out debt is low by global standards, and as a proportion of GDP is around half that of the UK and US, and less than a third of Japan’s.

Choosing a flattering metric, Frydenberg said our interest bill (on gross debt) next year will be $1bn lower than it was two years ago.

In truth our debt servicing as a share of GDP has been unchanged over the Coalition’s entire term, and net debt will be 0.7 per cent over the four-year budget period.

What if borrowing costs rise? Treasury has looked at alternatives paths of 10-year bond yields compared to its budget baseline. At worst, if bond yields converge immediately from current levels over five years to a long-run rate of around 5 per cent, gross debt would rise to 56.3 per cent of GDP in 10 years’ time.

Despite recent increases in bond yields, the weighted average cost of Frydenberg’s new borrowing in this budget is assumed to be around 1.6 per cent. Treasury projections are that nominal GDP growth will exceed the nominal interest rate for at least the next decade: debtors’ heaven.

Josh Frydenberg’s abiding obsession is jobs and growth, while the nation’s debt will eventually take care of itself.