Blitz on dodgy developers of high-rise towers

Regulators will be given powers to block suspect developers from erecting high-rises and builders will be rated on quality.

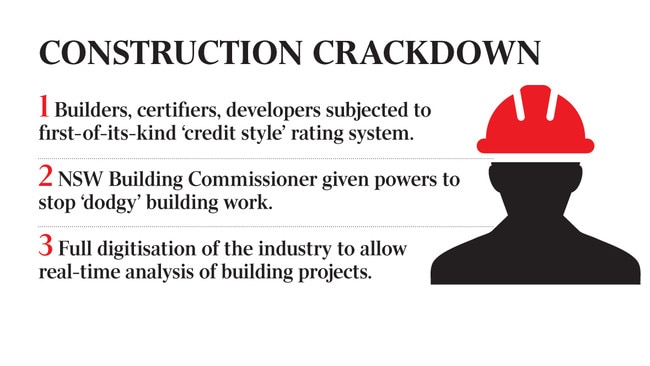

Regulators will be given powers to block suspect developers from erecting high-rise unit towers and builders will be subjected to a quality-rating regime based on their histories, under a NSW government crackdown on the construction industry.

Designed to prevent repeats of the Opal and Mascot Towers crises, the reform package — likely to form a blueprint for a national industry shake-up — will grant sweeping powers to the NSW Building Commissioner to stop defective apartment blocks from being built, particularly if they are linked to contractors with poor track records.

Construction plans will have to be downloaded to a centralised computer to allow instant access in the event of an emergency or a structural defect crisis.

The reforms will be presented to a national meeting of building ministers next month by the NSW Minister for Better Regulation and Innovation, Kevin Anderson, who will push for aspects to be adopted nationally.

“I’ll be very proud and honoured to take this building reform forward,” Mr Anderson told The Australian. “Those who cut corners, cut costs, those who will sign a contract and start skimming off the top — they know who they are. The good developers in this city and state want them gone.”

The new regulations will for the first time rank builders, developers and certifiers according to their record on workplace safety, their track record on customer complaints, the age of their business, financial credibility, suspicions of phoenixing, and dozens of other metrics.

They would be given a score akin to a credit rating. Those with poor scores would be flagged on a database to ensure their practices were heavily scrutinised.

Building Commissioner David Chandler will be given the power to block the building and remove an occupation certificate if a project is deemed unsound or the commissioner is not satisfied with the contractors. Without an occupation certificate, a development will be unable to settle with buyers.

If the power is invoked, investors will have their deposits returned and the building will not proceed.

“The builder and developer will be left with a building they can’t put up,” an official familiar with the matter said.

“You might be a developer with a clean record and you go with a particular builder and certifier, but they may affect your score because of their history. It will drag down the development score.”

The reforms have been developed in part to restore confidence to the sector, which has faced increased scrutiny since the 2017 Grenfell Tower disaster in London where 72 people died after being trapped in a fire in a high-rise apartment block covered in combustible cladding.

About 500 buildings in Victoria were found to need rectification work to remove flammable cladding, and similar numbers were discovered in NSW. Pressure grew for building industry reform after structural defects discovered at Opal and Mascot Towers in Sydney in 2018 and 19 required hundreds of people to be evacuated for months while the buildings were inspected and repaired.

The Building Commissioner has committed to the total digitisation of the sector, which currently works on outdated paper filing and analog systems. This would allow key documents such as construction plans to be instantly accessed in the event of an incident. Emergency service workers would also be able to access the digital platform. In the event of a fire, first responders would be able to view the building’s layout prior to their arrival.

At the height of Sydney’s Mascot Towers crisis in June last year, when hundreds of residents were evacuated after the discovery of structural flaws, engineers who went looking for the building’s layout plans discovered they had been filed in a storage unit several hours’ drive up the NSW coast.

“The council’s supposed to have them, and they said they were in a storage shed, so people have gone up the coast to trawl through and find them,” said the official familiar with the matter.

To bring the changes into force, Mr Anderson will need the NSW parliament to pass the Design and Building Practitioners Bill, a contentious piece of legislation that was pulled from an upper house vote last year.

The new regime, revealed by The Australian on Tuesday, was not detailed in the bill and would be implemented by regulation. However, the new regulations require the passage of the bill to be implemented. The bill passed through the Legislative Assembly but was halted in November when Greens MP David Shoebridge and Labor deputy leader Yasmin Catley called for significant amendments, citing flaws and misgivings about the legislation’s scope.

Industry is largely supportive of the bill, describing the need for reform as a matter of urgency. Master Builders Association executive director Brian Seidler expressed support for the new regime. “You’re never going to get everybody happy with these things, but in general terms the industry was accepting of the bill as it was,” Mr Seidler said.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout