Australia spends too much on childcare now, but it is not enough for Albanese

Childcare funding is about ideology, not economics, and if Labor gets to implement its policy we can kiss the top 47 cent tax rate goodbye.

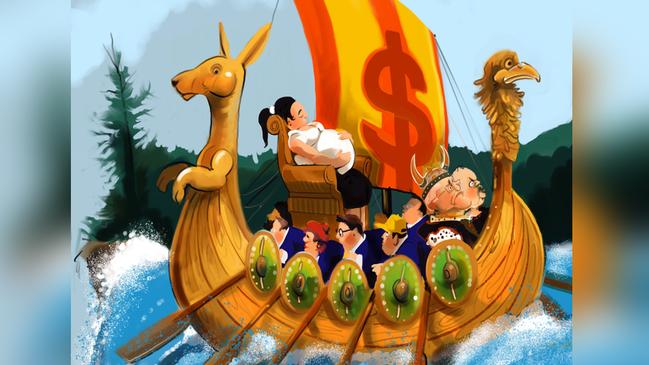

It’s a pity we’ve chosen to copy Scandinavia not on its relatively sane response to the coronavirus but on its tax and spending policies. Government spending in Denmark and Sweden, for instance, is more than 50 per cent of gross domestic product.

Even with a 30 per cent coronavirus surge to $677bn this financial year, Canberra plans to spend “only” 34 per cent of national income at this stage.

The Danes and Swedes, yet to embrace modern monetary theory, pay for it though, with equivalent top tax rates of 56 per cent and 57 per cent respectively, which cut in at about 1.4 times average full-time wage — $105,000 a year in the Australian context.

Josh Frydenberg has confirmed the Morrison government, fresh from bringing forward some tax cuts slated for 2022, still plans to lift the top marginal tax rate of 47 per cent to $200,000 in 2024.

That may not happen if Labor gets to implement its universal childcare policy, born of the absurd idea that the federal budget handed down last week was anti-women.

The government already spends more on childcare as a share of GDP than socially democratic Germany, The Netherlands and Austria, and about the OECD average.

Federal spending on childcare, supercharged by the Coalition’s 2017 reforms, is on track to rise 30 per cent from last financial year to $10.3bn by 2024, according to the budget.

That’s not enough for Labor which, we learned in Anthony Albanese’s budget reply speech, wants to increase the subsidy per dollar families spend on childcare from 85c to 90c.

Reflecting its base among high-earning public sector workers, where two incomes easily lift household income above $189,000 a year, Labor would scrap the cap of $10,500 per child a year that applies at that level of household income. Households earning below $530,000 a year — basically all of them — would receive a subsidy.

The government screamed “upper-class welfare” but it was crossbench senators David Leyonhjelm and Derryn Hinch who imposed a modicum of discipline on the Coalition’s own childcare reforms in 2017, capping support at household income of $350,000.

We are well past the optimal quantum of childcare funding, which increasingly forces the childless to subsidise the career ambitions of well-off parents who would have had children anyway.

It’s understandable high-income earners advocate universal childcare, making all sorts of fabulous arguments about how it’s good for the economy and GDP. While formal childcare can pay developmental dividends for children in single-parent or lower socio-economic households, for children in other households it’s glorified childminding.

Of course putting children in childcare adds to GDP: parents caring for their own children don’t count in the formal economy. Fees to childcare centres do, as do wages earned in a job. But this says nothing about prosperity.

Advocates overlook the cost of raising the funding: the distortion of higher taxation and the goods and services those taxpayers would have bought instead.

But it’s worse than that. Excessive childcare subsidies create childcare jobs that wouldn’t have existed otherwise. They can lure parents into work that — even with the taxpayer subsidy — pays little more than childcare workers earn, implying it would be better if they swapped jobs and left the poor taxpayer alone.

And, naturally, childcare centre owners cream off as much of the public subsidy as they can, knowing government will pick up the bulk of the fees charged.

Childcare funding is really about ideology, not economics or fertility. It’s about socialising child-rearing and “empowering” women.

Labor is opposed to the third stage of tax cuts, for instance, which would return years of bracket creep for those earning above $180,000, yet it is happy to give the same households sizeable handouts for childcare.

The great increase in female workforce participation — and collapse in fertility — occurred in the 1970s, long before significant childcare subsidies emerged.

Scandinavian nations spend double what we do and have similar female workforce participation and fertility rates. Even if childcare did boost fertility, with almost eight billion people on Earth (up from 4.4 billion in 1980) the case for subsidising people to have more isn’t obvious.

Economics has long considered work a disutility, something you avoid if you are fortunate enough to be able to. Childcare advocates see having women in paid work as desirable in and of itself, independently of what women themselves want.

If families want to use childcare that’s fine, of course, but why should others — including families that choose to look after their children — pay for it?

Government could make childcare more affordable by paring back the so-called National Quality Framework, which micromanages supply.

If parents don’t care whether staff have Certificate III, let them pick a cheaper centre that doesn’t care either.

If there’s to be a bias in the system it should be towards parents caring for their own children, the most efficient transaction of all, even if it’s ignored by GDP — one sustained by love, not money.

Taxpayers already fund primary and high school education, and a multitude of other payments and benefits in kind. Can we draw the line somewhere, please?

In economic terms, children once had the characteristics of an investment from the perspective of the parents: more hands to work on the farm, daughters to sell off for dowries, and for some help in old age, and so on. But today they are more akin to consumption.

“A very young child is highly labour-intensive in terms of cost, and the rewards are wholly psychic in terms of utility,” Nobel prize-winning American economist Theodore Schultz noted.

“From the point of view of the sacrifices that are made in bearing and rearing (children), parents in rich countries acquire mainly future personal satisfactions from them.”

Our future is Scandinavian, though. The share of net taxpayers is dwindling, already well below half of households. The idea spending needs to be paid for by taxation or borrowing is becoming old-fashioned.

And identity politics demands governments “do more” for women. Goodbye, top 47 cent tax rate.