Aged-care royal commission recommendations should be implemented quickly

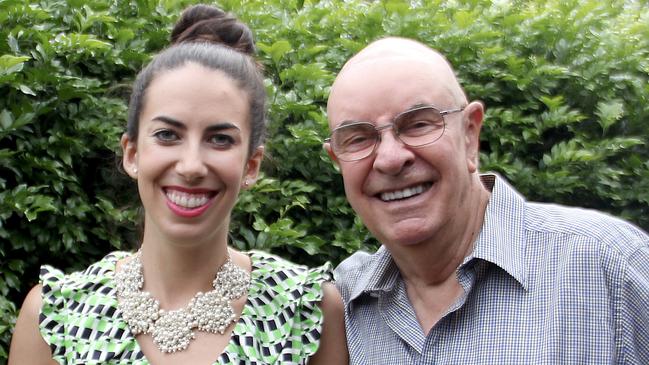

My father experienced the full gamut of the way Australia’s aged-care system can fail an older person: he sustained serious infections and injuries that went unnoticed; his medication was mismanaged; he fell repeatedly due to a lack of staff to assist him, ultimately leaving him wheelchair bound; he suffered undiagnosed and excruciating broken ribs with no pain relief; and ultimately he was sadistically abused by a carer who taunted and belittled him in his most vulnerable state.

The regulator which was supposed to protect my father’s rights failed him too: it did nothing to pursue either the provider or the care worker involved, and there were no consequences for either. My father’s provider has continued to pass every single quality standard with flying colours.

Now we have the commissioners’ historic final report, which confirms what we have known all along. Too often, Australia’s aged-care sector fails to care for our elders with dignity and respect, and traduces their human rights. Too often, vulnerable older Australians experience appalling failures of care in their final years: physical and sexual assaults, dehydration and malnutrition, preventable injuries and deaths. Too often, the toothless regulator allows negligent providers to continue operating with impunity, and too often providers are driven by profit rather than care.

Coming on the heels of more than 20 exhaustive reviews and inquiries into aged care over the past 20 years, the royal commission was arguably a redundancy — but one which has hammered home the urgent need for aged-care reform. The community is now well versed on the horrifying extent of the aged-care crisis. It will expect swift and transformative change.

The Morrison government has repeatedly invoked the royal commission’s work over the past few years as its rationale for stalling on challenges such as chronic understaffing, lack of staff training, rampant profiteering, and the lack of transparent and rigorous regulation. These assurances that the government has been waiting for the royal commission’s work to conclude have been of no help whatsoever to the vulnerable older Australians experiencing failures of care every day.

No more excuses

Now, the time for equivocation is over. The government has no more excuses not to act.

The Commissioners’ final recommendations propose major changes which will doubtless improve the current system if implemented, including a new human rights-based aged care act, introducing critically needed staffing minimums, clearing the home care waitlist by the end of the year, a scheme to register and regulate personal care workers, publicly publishing information on providers’ performance, improving the transparency of providers’ financial practices, and enhancing regulatory enforcement powers.

Yet the commissioners have been derelict in delivering a report that is split on key issues. In doing so they have let down older Australians, especially those who bravely testified at the commission, by failing to provide a clear and authoritative road map ahead to a recalcitrant government.

As was foreshadowed by the two commissioners’ extraordinary public disagreement in late 2020, they have delivered a split verdict on the regulation and funding of the sector. The royal commission heard extensive and compelling evidence about the inadequacy of the present regulatory regime, including the repeated, well-documented instances of providers failing quality standards repeatedly with no sanctions or consequences, and a paucity of on-site inspections.

In spite of this, commissioner Lynelle Briggs has reached the mystifying conclusion that the bureaucrats and infrastructure responsible for the current stagnant and toothless regulatory regime deserve a second chance — or, more accurately, one more in a series of seemingly inexhaustible second chances. Commissioner Tony Pagone QC reached the opposite view, recommending that an empowered statutory body independent of the Department of Health should administer and manage the sector.

The commissioners are also divided on the way the sector’s funding levels are determined. These unprecedented and intensely disappointing disagreements give the government cover to equivocate further.

Among the report’s 148 sweeping recommendations, there are some oversights. The Commissioners have included no specific provisions beyond the impending Serious Incident Response Scheme to tackle the epidemic of sexual assaults and rapes in residential aged care — yet evidence presented to the commission indicated sexual assault in aged care occurs at an alarming national rate of approximately 50 incidents per week. As the country convulses with calls for justice for younger women who have endured sexism and sexual violence in politics, we must not forget the older women in aged care who endure unacceptable levels of sexual violence, and deserve justice too. Likewise, there is an emphasis on introducing further civil penalties, rather than criminal ones, placing the onus on families to pursue justice on their own.

Government must step up to the challenge

The commissioners have also revisited extant remedies from previous reviews in their final report. Public reporting of complaints and investigations, the implementation of a public star-based rating service to track provider performance, increased powers for the complaints commissioner, and the adoption of clearer clinical care measures in the assessment and accreditation processes were all recommended in the 2017 Carnell-Paterson Review — but were not subsequently been implemented by the Morrison government.

The question is not whether the royal commission’s recommendations would improve the system, but rather, whether the Morrison government has the courage to implement them, and with the alacrity the crisis requires.

There are lingering doubts about whether the government has the ticker for the scale of change that is required to truly transform the aged care sector. On its watch, providers have repeatedly failed quality standards with few consequences; older Australians have continued to suffer shocking failures of care as recently as last week, at the Regis Nedlands facility; and providers have continued to post profit in the hundreds of millions with little transparency about their practices or performance. The shameful home care waitlist, which was singled out as an area of urgent action in the royal commission’s interim report, Neglect, still hovers at 100,000 — almost exactly where it was when the Prime Minister called the royal commission back in 2018.

There are early indications that the government may baulk at some of the royal commission’s key recommendations. In the commonwealth’s response to counsel assisting’s recommendations at the end of last year, it indicated that it would oppose introducing minimum training requirements for personal care workers in the form of the Certificate III, noting that in its view, all is required is “the right attitude and aptitude” among staff. Older Australians in care who experience repeated failures of care due to under-trained and under-qualified staff — as my father did during his final years — deserve much better than this.

Likewise, while the royal commission would like to see the initial prescription of antipsychotics limited to geriatricians and psychiatrists to reduce the prevalence of chemical restraint caused, in part, by GPs overprescribing antipsychotics. The commonwealth indicated it opposes this measure too.

We can write our own futures

Most concerningly, the commonwealth indicated it will seek to lengthen the timeline for several key action items, given the scale of work required. Tough questions must be asked about what groundwork has the federal government done to prepare for this moment. It has known for years that this report was be coming, and could also to anticipate many of its likely findings. What has it done to prepare for the workforce required for the increase in staffing it has known will be a central plank of the final report? What has it done to encourage new home care providers to enter the market and ensure they provide quality services, given the influx of care recipients as the waitlist is cleared?

The pandemic has revealed the agility with which the government can respond to complex challenges when the impetus and will are present: massive programs such as JobKeeper and JobSeeker were devised, planned and implemented within months. So why should aged care residents wait years to see change in the wake of a royal commission?

The royal commission’s road map indicates a five-year timeframe to achieve change. Yet the average stay of a resident in aged care is 2½ years, meaning that even if all the recommendations were implemented according to the royal commissioners’ proposed timeframe, a resident entering care today would likely not live to see the adoption of a new Aged Care Act, nor would they receive the optimum mandatory staffing standard of 215 minutes per day per resident, which will not come into effect until July 1, 2024, or the minimum of one residential nurse on-site at all times, which likewise will only come into force in 2024. Where is the urgency?

The royal commission is over — but it is what the Morrison government does next that really counts. As we reform our aged care system, we must remember we are writing our own futures: Australians over 70 have a 55 per cent chance of entering an aged care home. Sadly, change will come far too late for my father and those like him, but it is not too late for our grandmothers and parents, friends and partners who are about to enter the system. We owe it to our elders, and to our future selves, to demand major reform, and demand it now.

More Coverage

Two years ago, Prime Minister Scott Morrison called the Royal Commission into Aged Care in the name of people like my father: those who had been inexcusably failed by Australia’s broken aged-care system.