ACT Greens Attorney-General Shane Rattenbury faces significant questions over his #MeToo crusade

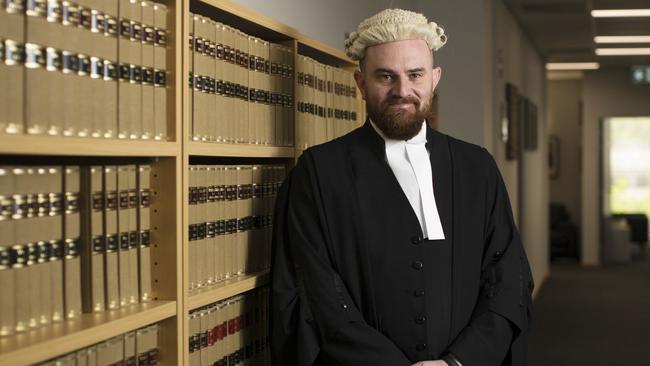

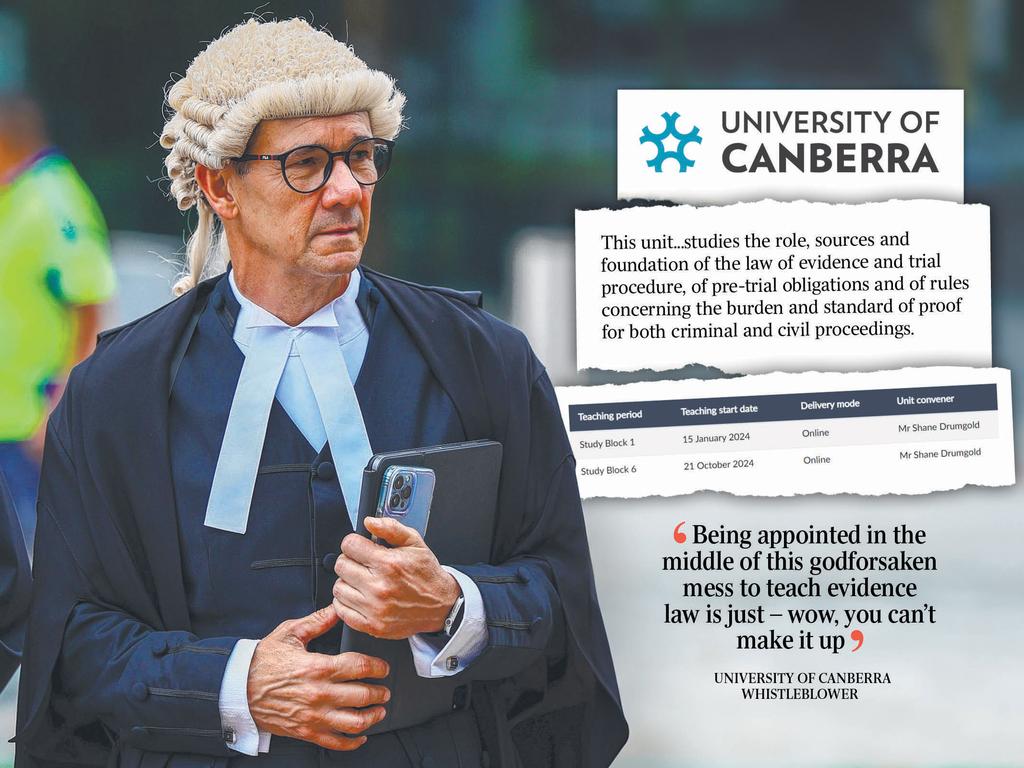

It was Shane Drumgold who first made explosive allegations that there had been political interference, specifically by Senator Linda Reynolds, in relation to the investigation and prosecution of Bruce Lehrmann for the alleged rape of Brittany Higgins.

Drumgold’s allegation was found by Walter Sofronoff KC to be utterly without merit. So much so that Drumgold was forced into a humiliating withdrawal of the allegations and Reynolds won a grovelling apology and damages from the ACT government when she sued it and Drumgold for defamation over the allegations.

Now, there are new and bigger questions. And the politician whose conduct deserves further investigation is ACT Attorney-General Shane Rattenbury.

Our news story raises significant questions.

By hauling the ACT Acting Director of Public Prosecutions Anthony Williamson SC into his office in late January, did Rattenbury expressly or impliedly use political influence to try to keep undeserving prosecutions alive?

That Rattenbury could have questioned Williamson about the discontinuation of sexual-assault cases at a time when he was actively considering whether Williamson should be appointed as DPP on a permanent basis is disturbing. Does the Attorney-General understand that the proper administration of justice demands that the DPP is an independent statutory office and must remain independent from the government and the politics of the day?

Why would Rattenbury question Williamson about the discontinuation of specific cases?

Was Rattenbury sending Williamson a message that he was watching discontinuations carefully and that it could be a factor in his choice of a permanent DPP?

Though Rattenbury says a selection panel, and cabinet, picked Victoria Engel SC as the new chief prosecutor for the ACT, does Rattenbury’s involvement mean that many might think the chosen person was regarded as more likely than other candidates to run as many sexual-assault cases as possible even if they have dubious prospects of success?

Discontinuation of sexual-assault cases is not done lightly. There is a lengthy and robust process before any such decision is made. A discontinuation may, by far, be the best course of action not merely for those wrongly accused of sexual assault, but also because it spares complainants possible humiliation as well as avoiding the burden on our courts, police, jurors and lawyers caused by weak cases that should never have been brought.

Rattenbury is, of course, a member of the Greens, whose political base is full of activist feminists who trumpet the “believe all women” mantra and want much higher levels of prosecutions and convictions for sexual-assault cases. With ACT elections in October, no doubt Rattenbury will be mindful that many of his potential voters hate the discontinuation of sexual-assault prosecutions. Whether he goes too far to keep his base happy is the question that the public deserve to have answered.

This is a most serious issue all over the country. Judge Robert Newlinds, a NSW District Court judge, expressed the fear that grips many rational observers about the way DPPs around the country are running sexual-assault trials. He recorded his “deep level of concern that there is some sort of unwritten policy or expectation in place in the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions of this state to the effect that if any person alleges that they have been the subject of some sort sexual assault then that case is prosecuted without a sensible and rational interrogation of that complainant so as to be satisfied that they have a reasonable basis for making that allegation”.

In the ACT, however, the concern runs even deeper. Not only should voters be asking how and why prosecutors get appointed, and how and why sexual-assault cases are commenced, but they need to be asking serious questions about how these cases are conducted once they get to court.

On the evidence of Drumgold’s admissions, we know he withheld evidence from Lehrmann’s defence team that they were entitled to, that he misled the Chief Justice in the course of the trial and that he procured his most junior employee to swear a false affidavit. God only knows what we don’t know.

Drumgold’s misbehaviour should not taint other ACT prosecutors who behave professionally while carrying out their important roles. However, Drumgold’s former status as chief prosecutor and his ability to direct more junior employees does raise questions about the culture of the Office of the DPP.

There are other pointers to systemic failure in the ACT. As The Australian has reported, when Lehrmann sought legal aid in the ACT, he was told that the Legal Aid lawyers would not challenge the complainant’s credibility. In other words, if you are poor and an alleged perpetrator of sexual assault in the ACT, you can forget about getting legal aid to run a proper defence.

Even more concerning is that, as far as we can tell, none of the official pillars of the ACT justice system – from the Chief Justice down to the ACT Bar Association – has yet taken any measures to discipline Drumgold for his admitted misconduct.

Is this a sign that legal luminaries in the ACT are willing to turn a blind eye to the fact that a chief prosecutor misled the Chief Justice in the course of a trial, withheld evidence the defence was entitled to and connived at the swearing of a false affidavit? For so long as there is silence from lawyers charged with overseeing the administration of justice about serious questions hanging over the ACT justice system, there will remain a serious whiff of class warfare in the ACT air.

Rattenbury’s hard-line ideological determination – aided and abetted by the radical adherents of the #MeToo movement, to get prosecution rates up apparently without apparent regard to the disastrous consequences of failed prosecutions not merely on complainants and alleged perpetrators but on police, judges and juries – makes us wonder what is really going on here.

Is this a case where young males have become the 21st century Kulaks, a despised class enemy whom the government feels entitled to persecute at will?

It is the supreme irony that we may have been looking in the wrong place for possible political interference in the way law-enforcement officers in the ACT conduct prosecutions of sexual assault cases.