Pandemic exposes cracks in the Asian Century

The pandemic has shaken confident predictions for the so-called Asian Century.

The smart phone was just lying on a table in a neighbouring house when in a split-second decision motivated by poverty, shame and a longing to give his child a better life, Ajang Elan put it in his pocket.

“I didn’t think twice. I took the phone so my daughter could study. I don’t want her to turn out like me,” the Indonesian labourer — whose income has all-but dried up — told The Weekend Australian after narrowly avoiding criminal charges thanks to the understanding of a local prosecutor.

“We had been borrowing (another) neighbour’s phone but I felt ashamed. We couldn’t do that every day. My daughter is so eager to learn.”

The rare reprieve for the impoverished father of three underscores the hardships being borne by the most vulnerable during a pandemic that is showing no sign of abating. But it also highlights weaknesses in the response.

Since Ajang’s case was made public last month, officials have worn a path to his one-roomed shack in West Java, offering food aid, a phone, even a laptop for his 13-year-old daughter Sinta, who says she feels “sad and ashamed” of what her father did for her.

Across Indonesia millions of people are falling between the cracks as the government struggles to distribute social assistance packages to those who need it most. For the many already living hand to mouth across Southeast Asia, including 200 million informal workers — maids, street-sellers, ride-sharing motorbike drivers — even the weakest economic shock can push them below the poverty line.

In a recent blog, economists writing for the International Monetary Fund stated what should now be obvious to everyone: most developing nations can’t afford to lockdown because so many of their citizens live at near-subsistence levels.

Yet in Indonesia there is fierce debate over whether government reluctance to pull the brakes in the middle of a COVID-19 infection surge will prolong the country’s economic suffering. One economist told a parliamentary committee this week that economic recovery would be possible only when the outbreak was under control.

“I’m afraid the government response seems not to care about COVID-19, they’re only focused on economic recovery,” University of Indonesia senior economist Faisal Basri told the hearing. “We need to control the virus spread before the economy can grow.”

Indonesia’s economy shrank 5.3 per cent last quarter, the worst contraction since the 1998 Asian financial crisis, though far less than many of its neighbours whose economies are more trade and export-oriented.

There is more bad news ahead thanks to spiralling infections, now almost 190,000 nationwide, which are hobbling efforts to reopen the economy.

Respected SMERU Research Institute estimates that if the Indonesian economy grows 1 per cent this year, higher than Finance Minister Sri Mulyani’s most optimistic prediction, 8.5 million people could fall into poverty (12.4 per cent of the population). Should the World Bank’s worst-case estimate come to pass, and it shrinks to -3.5 per cent, 19.7 million people will become newly poor.

“That would wipe out all the poverty reduction of the past decade in Indonesia,” says SMERU researcher Ridho Al Izzati. “Social protection must improve. Not just for poor people but for vulnerable people who are at high risk.”

While government assistance is now reaching 30 million households, “it’s not necessarily the right 30 million”, he adds.

Hal Hill, an Australian National University professor emeritus of Southeast Asian economies, says the pandemic has highlighted a “rich country, poor country divide” where wealthy nations are devoting huge stimulus packages to keeping their economies turning while developing nations struggle with limited finances, weak institutional capacity and incomplete registries of the poor.

“We in Australia can afford to have nine to even 15 per cent of GDP in stimulus packages. Indonesia would be lucky to get 2.5 per cent in GDP stimulus,” he says.

East Asia is still the world’s most dynamic region and will likely “lead the global economic recovery when it does happen”, he says, though The Philippines and Indonesia — countries with weak health systems still grappling with rampant community infection — could be slower to recover.

There will also be opportunities for ASEAN nations as recovering economies look to diversify their value chains outside China.

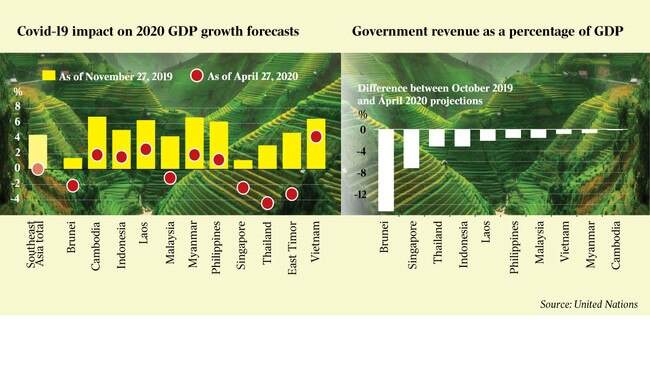

Still, the pandemic has shaken confident predictions for the so-called Asian Century; that the continent would generate more than half of global GDP and half the world’s middle class by 2040. Countries that were expected to help drive that growth — Indonesia, The Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia — have all had dramatic COVID-fuelled economic contractions.

Across Southeast Asia, demand has plummeted because of mass job losses and movement restrictions, while supply has dropped because of factory and business shutdowns.

Thailand and Malaysia may have weathered the infection storm better than most, but their export and tourism-reliant economies have been among the region’s worst-hit. Thailand’s is projected to shrink a record 8.5 per cent this year.

In The Philippines, which experienced a record 16.5 per cent economic contraction in the second quarter, 500,000 migrant workers have returned home jobless. About 200,000 more are stranded overseas, and the government estimates a million overseas workers will have lost their jobs by the end of the year.

Cambodia’s economy is tipped to shrink as much as 5.5 per cent this year and the Asian Development Bank has warned the pandemic could push 1.3 million more Cambodians into poverty.

India’s economy shrunk 23.9 per cent in the three months to the end of June, its worst slump since 1996 and the steepest contraction of the world’s large economies. About 19 million formal-economy jobs have vanished since its draconian lockdown ended in May. All it did was delay the rampant spread of infection across the country which, on a single day this week added 83,000 new cases. India has 3.9 million infections.

Even in Vietnam, the only Southeast Asian economy not tipped to fall into recession this year, 30.8 million Vietnamese had been affected by the pandemic by July, either through job loss or pay cuts, according to the government’s own statistics.

These are not just bad economic numbers. They represent hardship, hunger, lower education and health levels, and lost opportunity for millions of Australia’s neighbours.

A survey by independent pollster Social Weather Station estimated 5.2 million Philippine s families had gone hungry in the past three months because they couldn’t afford food.

Child marriage rates in India and Indonesia — two of Asia’s hardest hit countries — are rising as families plunged into poverty marry off their young daughters. Indonesia’s Women’s Empowerment and Child Protection Ministry reported 33,000 child marriages were approved by the country’s Islamic authorities between January and June, compared to 22,000 for the whole of last year.

Doan Thi Thanh Ha, an economist with the Economic Research Institute of ASEAN and East Asia, says estimates from as recently as July don’t reflect the potential depths of the region’s economic woes given recent fresh infection waves.

“In the long term, poverty and inequality will be a significant problem because once people fall under the poverty line it doesn’t just impact their generation but the next generation also,” she says.

“GDP will probably bounce back after several years but the income gap between those not effected by the pandemic and those who are forced below the poverty line will be larger.

“If inequality effects the income of the parents we would also expect it to effect the health, education and other opportunities available to their children, so it’s a vicious cycle and it can take several generations to get out of that.”

Filipino father of three Jesus Gaboni is desperate to protect his family from that fate.

The 48-year-old lost his job as a contract fisherman on a Chinese trawler in April though it wasn’t until his boat docked in China in late May that he discovered the reason for his unemployment was a global pandemic.

It would be July before he was united with his wife and sons in Manila, owed more than $1500 in unpaid wages and facing a pile of household bills.

With no jobs available, his wife in only part-time employment, he now earns 100 pesos a day ($2.79) selling iceblocks around his neighbourhood. It is enough to buy a kilogram of rice, some vegetables and daily internet top-ups for his kids’ online schooling. Everything his wife earns as a clerk goes on water and electricity.

“We are only able to eat two meals a day, if it’s a good day,” he tells The Weekend Australian. “We’re really having a hard time. My children are feeling the hardship. Before the pandemic my family could afford to eat beef and chicken. I could even afford school transport for my kids.”

Now the three boys, the oldest in Year 12, share one mobile phone for their online lessons.

Gaboni says many neighbourhood kids have had to drop out of school since the pandemic began, but he and his wife are determined to give theirs a better life. “We don’t want our children to go through this suffering,” he says. “We will do everything we can — no matter how hard it is — to give them an education.”

Additional reporting: Chandni Vasandani, Feri Purnama

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout