One woman’s quest to educate her kids – and anyone who comes

Hours from any school, and overlooked by the NT government, Michelle Kmon started teaching her kids from home and things grew from there.

At the top of the red-dirt cliffs overlooking the pristine waters of the Cobourg Peninsula in the Northern Territory, four-year-old Shiloh Cooper hitches up the purple tutu she has teamed with her fishing shirt and climbs on to a wooden picnic table ready for lunch. She and brother Lui, 7, dig their fingers into the soft meat of the turtle caught earlier this morning by their dad, Dylan Cooper, an Arrarrkbi man and local ranger.

“It’s very relaxed, it’s really good for the kids because the kids are always outside running around playing,” says their mother, Michelle Kmon, looking out at what is essentially their backyard. “They get to go fishing constantly, hunting with their dad, and they just get to be on country.”

As the kids pick at the meat-laden marine shell, the family discusses their plans for the day. Even though it’s a weekday, Lui and Shiloh won’t be going to school. The closest mainland school, Gunbalanya, is a four-hour drive along an unforgiving dirt road that gets cut off in the wet.

Their grandfather, Solomon Cooper, a traditional owner in the Cobourg Peninsula area, grew up here back when there was a school. It was called Thunder Rock and he attended in the 1980s, but the government closed it down in 1996. Now, aside from Gunbalanya, the only other nearby option is Croker Island – but they’d need a light aircraft to get there.

Solomon Cooper would like to see education for his grandchildren here. “Nothing too flash,” he qualifies. “Something where the kids can call a school.”

Remote living an adventure

Kmon was on maternity leave from her teaching job with the NT Department of Education in Darwin when the family moved in late 2019 so Dylan Cooper could take up a ranger position.

She says it was good timing for the young family to move to the Cobourg Peninsula – part of the Demed Homelands, a 2,360,000ha expanse of bushlands. The region has a population of 279 according to the 2021 census, but Black Point ranger station, where they live, is home to about 13 people.

Kmon enjoyed the adventure of remote living, but as a teacher she began to see the impacts of a community with no school. Another ranger family lived in the area and the parents were struggling to teach two kids at home.

“I wanted to keep myself busy but I also really missed teaching,” she says. “I loved teaching. And so I offered to tutor them.”

It was around this time Kmon wrote to Selena Uibo, then the Territory’s education minister, asking for guidance with developing a school. The response read: “The establishment of a new school requires extensive planning, consultation and resources. Currently, the Department of Education has no plans to establish a new school in Western Arnhem Land.”

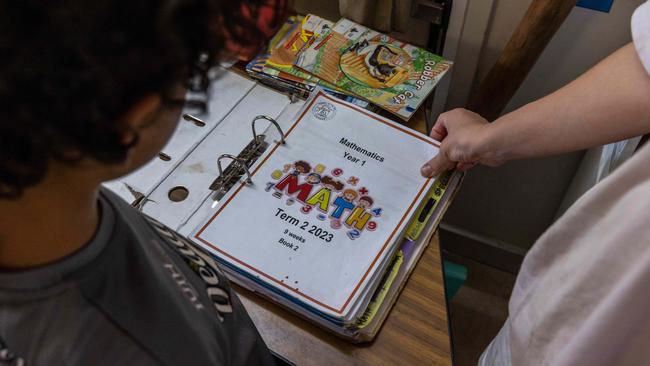

Kmon continued to teach the two children from her living room until mid-2020, when she was given access to a vacant ranger’s house, which she transformed into the unofficial Black Point Primary School.

The house wasn’t perfect – sometimes they needed to move for a meeting or a guest – but she needed the additional space because soon more students began turning up for her lessons. By the end of 2020, Kmon was voluntarily teaching five children, ranging from preschool to year one.

With no financial backing for the school, Kmon relied on donations to set up the classroom.

“I posted on (Teachers of Darwin & NT Facebook page) just saying did any schools have any tables and chairs that they’re wanting to get rid of,” she says.

She also received $3245 in donations from tourists and local businesses, which helped her buy supplies, and one parent donated the equivalent of their isolated children’s allowance to the school.

Solomon Cooper’s half-brother Shane Cooper lives 3km away at Gumeragi outstation with his partner, Fiona Cunningham. Soon they began sending three of their four children to Kmon for lessons, too. Cunningham, an Arrarrkbi woman, says she was grateful for the opportunity to send her kids to school. “Michelle was doing really good teaching Olivia, Steven and Michael,” she says. “They liked the school up there.”

Cunningham was having trouble with her car so, on top of teaching, Kmon would pick up the children and drop them home, as well as make their lunches. Sometimes the Gumeragi children would walk to school, stopping to fish or hunt on the way.

But running the school took a toll and Kmon says it caused some tension in her family, in part because she wasn’t being paid.

“Sometimes I’ve sat up until midnight trying to plan through everything as to how it’s going to work the next day,” she says.

It was also difficult keeping up with all the children’s needs. She says it was hard to manage the different ability levels in the classroom, especially as some of the children weren’t independent learners and needed one-on-one support.

Holly Bird, who helped run a tourism camp about a 40-minute drive from Black Point ranger station, sent her four-year-old son Jack to Kmon’s class when they lived there in the dry season. Later, her youngest, Finn, joined for two preschool terms.

Seeing the strain Kmon was under to keep the school afloat, in October 2020 Bird wrote to the then NT education minister, Lauren Moss, asking for advice and support. She was told to contact Katherine School of the Air and the director of Quality School Systems and Support Top End.

The letter noted: “I am advised that due to the low numbers of potential students and the appropriate access to distance education services, the Department of Education does not intend to establish a school in West Arnhem Land.”

By the end of 2021 Kmon was teaching 11 students, nine of them Indigenous, ranging from preschool to year 8, five days a week, and had another two children attending daycare with her once a week.

According to My School data, there are 10 government schools in the Territory with 13 or fewer students. Rockhampton Downs School has four students. All but one has at least one full-time equivalent teacher.

Stepping up

The Black Point community is not alone in having no access to school. The Australian has been told of other homelands in the Northern Territory where residents have been in touch with the Department of Education requesting a school be opened because of a growing number of children in the community.

At Dhipirri, about 350km northeast of Darwin in Arnhem Land, community members say they have been contacting the government for years about establishing a school. Today, a volunteer teaches students at someone’s house. The Australian understands there are 15 to 30 children connected with the homeland.

There are also examples of communities that fought for years before the Territory government agreed to open a school, and they often had to raise much of the funds themselves.

Biological anthropologist Neville White has recorded the struggle to establish a school in the Donydji community, 250km southwest of Nhulunbuy in northeast Arnhem Land, which had been trying to establish a school since the 1970s.

In 2001, what is called a Homeland Learning Centre – a small, remote classroom linked to a larger hub school – was established at Donydji that then was attached to Shepherdson College on Elcho Island. As an HLC, White says, Donydji was getting a teacher three days a week and students learned “under a bark and plastic shelter that had no protection from the wet season rain” or the hot dry season winds.

He says education authorities were approached for a classroom but they were told Donydji needed to show another 12 months’ commitment to schooling first.

“Instead of government saying: ‘Here are people who actually want to get on with their lives and educate their kids, let’s support them,’ they handball it back and say: ‘Show a greater commitment. That is, you have to stay out there through another wet season with no structure and then we’ll support it.’ That’s when we took a step and said: ‘This is disgraceful.’ ”

Instead, the Rotary Clubs of Victoria’s East Keilor and Melbourne stepped in to fund the school and Vietnam veterans constructed the buildings, alongside community members, in 2003.

To date, the Rotary Club of Melbourne has donated about $1.7m to the community to support schooling, training and housing.

Donydji now has a Homeland School managed by Gapuwiyak School, with a registered teacher, a (Yolngu) assistant teacher from the community and good support.

Just more than 100km north of Donydji at Mapuru, it was a similar story. The community had about 50 school-aged children and had been asking for a school since 1976.

John Greatorex, a former teacher at Elcho Island who has been involved with the Mapuru community since the late ’70s, and Linda Miller, who went on to become principal at Mapuru, say government policy required the community to build and run their own school with minimal assistance for six to 12 months before the request for an HLC would be considered.

Mapuru landowners pooled their money to build a classroom and a parent volunteered as teacher, and they were granted an HLC in 1984, but they still had only a registered teacher visiting part-time.

“In those early days a visiting teacher might or might not come once a week,” Miller says. “Out of sight, out of mind; principals needed to meet the needs of the hub school first and the Homeland Learning Centres later. In a good time, (Mapuru) was lucky to get a teacher there one to four days a week, and if you’re averaging 45 kids …”

Elders and parents wanted a teacher living on-site, so Mapuru moved away from being an HLC and established its own fully independent, locally governed school in 2018.

A Territory Department of Education spokesperson has confirmed there is no policy governing how HLCs are established, suspended, closed or reopened. The Australian understands almost all of the 31 HLCs in the Northern Territory are supplied a registered teacher only part-time, which has led to concerns about human rights violations.

Under the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, children in Australia have the right to an education and Northern Territory Anti-Discrimination Commissioner Jeswynn Yogaratnam says there must be different considerations for school resourcing opportunities when strategies and budgets are developed for remote schools.

“You can’t stop or reduce funding for teachers based on attendance. Schoolteachers are integral to student learning as well as other student needs that contribute to their wellbeing,” Yogaratnam says. “If you’re providing transportation services, a train service, irrespective of whether there’s one person or 100, that train is going to run based on that schedule.”

Yogaratnam says it should be the same in schools – whether there are five children or 500, there should always be a teacher there to deliver full-time schooling. “The sustained education system is so important,” he says. “It’s when there are gaps in that cycle, people then start to think that (education) is not a priority any more and stop trusting the system.”

Back at Black Point, Bird wrote a second letter to the Territory education minister in January 2021 asking about the possibility of becoming a Homeland Learning Centre. The reply provided contacts for establishing an independent school and becoming a HLC. The response gave Kmon hope.

“I got a little bit excited and thought: ‘OK, well, maybe we can do something’,” she says. By then Kmon had enrolled almost all of the children in the Katherine School of the Air program.

On the back of that correspondence, she approached the Quality School Systems and Support team to pursue the option of linking up with another government school such as Gunbalanya, but she was told it was not possible and that the program running at Black Point was already going well.

“I just got really frustrated because I thought: ‘He’s referring to Katherine School of the Air,’ ” Kmon says. “But the only reason why it’s working well is because I’m running it.”

While the teachers were very helpful and the curriculum was useful, Kmon says some of the children living at Black Point needed more support than School of the Air alone could offer. The program required an adult literate in English, and it fell to her to complete all the School of the Air applications for the Gumeragi outstation kids, whose first language is Iwaidja.

Once the program was running, it became clear it would be difficult for the parents to navigate the work packs, which she says were information-heavy with a lot of teacher-speak.

“Katherine School of the Air is a good program if you’ve got someone to be able to run it,” Kmon says. “It’s definitely not suited if you don’t have a tutor whose prime role is to teach the kids. They get paid to plan and do whatever they need to do. If you are trying to manage it as a parent with all your other kids, it’s virtually impossible.”

While experts say School of the Air and distance education isn’t designed for Indigenous students whose first language isn’t English, they do say there is potential to develop something that could work.

The recent 2023-24 federal budget announced $12.7m for a community-led pilot to look at more culturally appropriate distance learning.

Western education important

Solomon Cooper – or Solo, as he’s affectionately known – pulls up a plastic stackable chair outside Trepang Lodge and places a cup of tea on the wooden table.

From under the brim of his black Humpty Doo Hotel baseball cap he talks about what it’s like to be able to teach your grandkids on country.

“I tell them stories, sitting near the fireplace, I tell them about the creation,” he says, sipping his tea. “I tell them all this stuff – respect, what’s right, what is wrong. Hopefully, Shiloh and Lui will carry on.”

But he says it’s also important they have Western education alongside this.

“They (need to) learn both things – the normal ABC, the normal educational stuff; Michelle knows all that as a teacher. Then you got us, your grandfathers, fathers and uncles, and we teach our kids the cultural side of things – you know, languages, cultural, spiritual things.”

Kmon agrees the children get better cultural opportunities living at Black Point than they would in a bigger community or town.

“There were times that we were at school and the rangers, Robbie and Dylan, would come past and say: ‘Hey there is a big crocodile down at the swamp do you guys want to come down?’, and so we’d have a little excursion down to the swamp to go see the crocodile.”

Kmon understands it’s difficult to provide for a school in a remote location with low student numbers, but former Thunder Rock schoolteacher Rowan Simpkin, who was at the school from 1986 to 1989, remembers teaching Solomon Cooper and says student numbers were low back then and the school was still able to run.

“The numbers sort of varied if people were visiting, so there were times when I would have up to 12 or 14 kids, but most of the time, for the first year at least, there were only four and then it went up to sort of six, seven kids,” she says.

She says the school was “always very political” and she believes it was the passion of the local ranger at the time that kept the school going. “In those days politicians often went out there to go fishing and to have cabinet meetings and things like that,” she says.

Even the education minister at the time came to visit.

“He asked the community whether they’d like a computer, and they all said, ‘Yes, we would like a computer.’ And he said to me, ‘Oh, well, we’re going to get you a computer.’ And I said, ‘Oh, that would be great. But could we have electricity first?’ ”

In May last year Kmon had to close the school as she was due to have her third child, but she continued helping Cunningham from Gumeragi outstation, who kept teaching the Katherine School of the Air program to her kids at home. But that became too difficult and Cunningham made the decision to send her kids to school in Jabiru, more than 300km away. Eldest son Michael is happy there as he can play sports, but the younger ones, Steven and Olivia, enjoyed school at Black Point and would like to come back.

Now her baby is one, Kmon is eager to get the school back up and running, but while she was full-time parenting another problem cropped up: the Territory Department of Housing condemned the vacant house they were using as a classroom and bolted the doors shut. They have nowhere to go.

Black Point is closed

Lui’s school desk is pushed up against the wall separating the living room from the kitchen. His two sisters potter around him as the screen lights up and he puts on a chunky pair of headphones. His lesson is starting. Now Black Point school has closed he takes his classes at home.

“I feel a bit sad and that,” Lui says. “There used to be lots of kids to play with but now it’s just Shiloh.” He doesn’t want to go to town for school. “I like doing it out here because you see boats going past, you see heaps of sea turtles, you see heaps of dolphins and you get free rides on choppers.”

Solomon Cooper, who is also chairman of the Cobourg Peninsula Sanctuary and Marine Park board, says they have access to a trust fund, and there has been some talk about using it to build their own school, but an ongoing land claim has made it difficult to proceed.

“If there is a school here, they’ll bring their kids back here,” he says. “The kids are having an education here till a certain age and then we can send them to college or whatever.” He would like to see more support for his community – and for others trying to make schooling work in remote places.

“I’m going to do the best I can to try and get something happening,” he says. “Like I said, I’m not just talking for Michelle, but there are others out there. I know there are others out there.”

Lucy Periton is an independent journalist working in the Northern Territory and Queensland. This project was supported by the Meta Public Interest Journalism Fund.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout