No escape: family reveals Hannah Clarke’s marriage hell

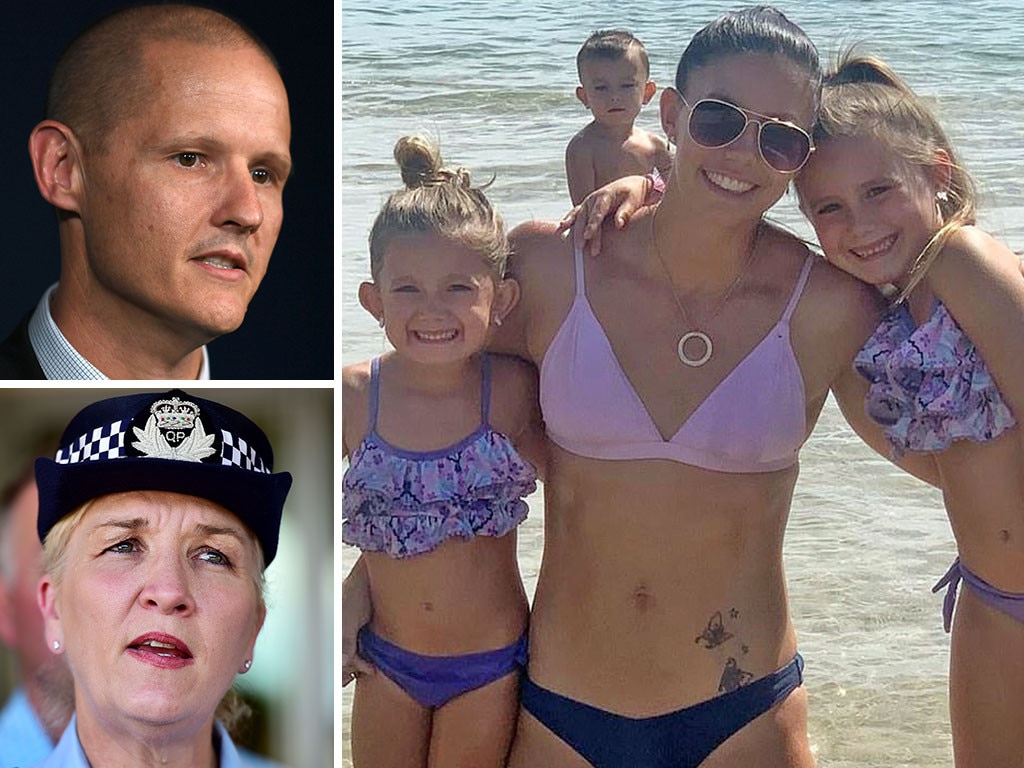

Hannah Clarke suffered years of mental torture but her final act of defiance after being set alight by her abusive ex showed her strength.

The man and woman bow their heads in front of the growing shrine of flowers, teddy bears and toys outside No 26 Raven Street, Camp Hill.

She is sobbing and he puts an arm around her, black scars on the bitumen beneath their feet, where the burning Kia SUV had come to rest. When they walk slowly away on Friday, they reveal their tears are from shame as well as grief.

“We’re related to Rowan,’’ the man says. “We feel so guilty, just knowing him.’’

On Wednesday morning, in an incomprehensible act of violence, Rowan Baxter ambushed his estranged wife, Hannah Clarke. She was driving to school with the couple’s daughters, Aaliyah, 6, and Laianah, 4, and son, Trey, 3. Baxter doused them with petrol and set them alight.

The attack followed a decade of emotional torment that had led Ms Clarke to leave her husband just months ago, family and friends said on Friday.

“It was always Rowan’s way or the highway,’’ said her father, Lloyd Clarke.

“Not all domestic abuse is physical,’’ added her brother, Nat.

Over time, Ms Clarke came to realise what was happening in her marriage, and left her controlling husband. Always looking to the future, brimming with positivity and happiness, she was going to give her kids a better life.

Baxter couldn’t accept it.

Raven Street residents were driven back by heat and flames as the vehicle exploded on Wednesday. They have described horrific scenes that lay bare the shocking reality of Australia’s ongoing scourge of male violence.

“He’s poured petrol on me,’’ Ms Clarke screamed, making it out of the car.

Murray Campbell points a shaking finger to the scorched grass outside his home, where Ms Clarke fell.

“The lady was screaming, ‘help me, my children’,’’ Mr Campbell says. “Then I realised, shit, there’s kids in the car. There’s nothing you can do. Within a minute they would have been dead. Within a minute. The flames, you’ve got to have seen it to believe it.’’

Ms Clarke, 31, succumbed to severe burns later that night in the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital.

Friends said she fought to the end, her family by her side. Baxter, 42, died on the side of the road from self-inflicted wounds.

In a family interview with the Nine Network’s A Current Affair, Ms Clarke’s parents and brother spoke on Friday of her bravery in leaving her husband late last year.

The night before the murders, Baxter was crying over the phone in a call to his children. Ms Clarke was sympathetic, said her mother, Sue. “When she hung up, or the children hung up, she said to me, ‘Mum I feel so bad for him’,’’ Sue Clarke said.

Before Hannah Clarke passed out, with burns to more than 90 per cent of her body, she had given police a detailed description of what her husband had done to her and her children that morning, her parents revealed. They believe it was a final act of defiance.

“To the end she fought to make sure if he survived he got punished for doing it to her babies,” Lloyd Clarke said. “She was so brave. She did everything for those kids.”

The family wants to raise awareness about how domestic violence can be mental as well as physical.

“Even Hannah, for a few years there, she said to me, ‘I was thinking it wasn’t abuse because he never hit me’,” Sue Clarke said.

“She had in her head as well that domestic violence was physical. It was psychological torture in the beginning.”

Baxter’s control of his wife included ordering her what to wear and not speaking to her for days if he did not get his way.

Ms Clarke’s parents regret not noticing the signs earlier.

Her bubbly, kind persona, they say, is one of the reasons Baxter thought he could control her.

His manipulation extended to social media, where he was diligent about portraying a happy family life that was far from the truth.

Ms Clarke kept the emotional and sexual abuse mostly hidden from her parents until last year when she decided she had to leave.

“I would ask her, but she would say ‘I’m fine, mum, I’m fine’,” Sue Clarke said. “I think she was scared to leave.”

Even when she made the decision to take her children and go, she had to plan an escape.

“Unfortunately she couldn’t say, ‘Rowan, that’s it, I’m going away for a while’,” Lloyd Clarke said. “She had to hide it. She had to wait until he went to work and pack everything up and then get the kids out of there.”

A “jealous and spiteful” Baxter continued to harass her, including a physical assault during a visit with the children last month.

The threats became so concerning that last week Ms Clarke asked her mother if she should prepare a will.

Her greatest concern was what would happen to her children when she was gone.

Despite this, her parents still had not believed Baxter was capable of hurting his own children.

“A loving father doesn’t do that,” Lloyd Clarke said. “It was all revenge at Hannah.”

Friend Manja Whaley said Ms Clarke lived in fear Baxter would harm her and her children if she left him, but initially struggled to accept this was domestic violence.

Ms Whaley, a domestic violence service worker, recognised the signs after meeting Ms Clarke at the couple’s Integr8 fitness centre in Capalaba, southeast of Brisbane, last year.

Ms Clarke confided in her that Baxter had spoken of threatening a previous partner that he would harm himself and his son from that relationship if the partner left him.

In a Facebook post after Ms Clarke’s death, Ms Whaley said: “At first you were confused and told me that you had never thought of being in a domestic violent relationship as you explained ‘he never hit me’.

“We talked about the different types of violence including financial abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse and you experienced all of them.

“This was not an act as a result of mental health issues or financial problems. This was a premeditated, deliberate decision.’’

Ms Clarke told friends she was so glad she got out when she did. But domestic violence advocate Betty Taylor, from the Red Rose Foundation, said leaving a troubled relationship was one of the most dangerous times for a woman.

“We get asked all the time, ‘why doesn’t she leave’. But the leaving itself can be a trigger,’’ Ms Taylor said.

“The research is showing that the first three to four months post-separation (is the most dangerous time). But sometimes homicides have occurred six to 12 months after because there can be new triggers.”

Ms Clarke had taken steps to keep herself and her children safe, obtaining a restraining order to keep her husband away from her. In the end it was just a piece of paper.

Ms Taylor said women should never underestimate what a possessive and controlling partner could be capable of.

“Sometimes if there’s no physical violence, people miss the signs,’’ she said. “Jealousy, possessiveness, stalking, tracking devices on cars and phones, messages they might write on Facebook, conversations they might have with their mates. All of those things can tell us how dangerous a person is likely to be.’’

Ms Clarke’s parents cannot bring themselves to think about the day their daughter and grandchildren died, so close to their home.

Their daughter was so badly burned that an imprint of the sole of her foot was the only identifying feature police were able to take as she lay in hospital.

They hope it can become a symbol of their daughter’s bravery and the steps that need to be taken to fight the scourge of domestic violence.

Ms Clarke’s friends have vowed to raise their sons differently, to become strong, not monsters, and bring about real change.