Just add Eyre and water: desert awash with new life

A flood raised in distant Queensland has taken until now to arrive in parched South Australia — and what an incredible sight it is.

The flood raised in distant northwest Queensland has taken until now to arrive, and what a sight it is.

The headwaters are the colour of coffee, thick with sediment, bursting with new life, advancing at a walking pace across the pearly expanse of Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre.

This is the moment of magic when the vast, crystalline saltpan starts to fill and the desert blooms, its sunblasted wastes turned lush in a cycle of bust to boom that is as timeless as the Australian outback.

From 2500m above the lake floor, the view is breathtaking.

The elongated finger of water creeps along a shallow channel called the Warburton Groove at 4km/h, the leading edge of a torrent that is backed up for hundreds of kilometres beyond the blanched horizon.

When the water reaches Belt Bay next week, it will fan out shin-deep, covering the lowest point of the lake.

Nature’s wake-up call precipitates an explosion of activity: pelicans feast on the black bream and yellow-belly callop that surfed the flood from Queensland like Noosa boardriders; shrimp-like copepods hatch from eggs that have lain dormant through the long dry; spiky lignum bushes sprout leaves and will soon flower under a gentle sun.

“This is the magic of inland Australia,” said Richard Kingsford, an environmental scientist who knows the Lake Eyre Basin like the back of his hand.

“This is what makes our continent and the river systems so different to the rivers anywhere else in the world; this is the absolute life blood.”

Station hand Laura Tuesley, 22, said the country had been bone dry for nearly as long as she had worked on Clifton Hills, a cattle property that’s two-thirds the size of Israel. It hasn’t rained since last October, but no matter: the flood has taken care of all their water worries.

“It’s awesome,” she said, standing on a muddy bank of Warburton River. “There is nothing better than seeing a flood in this country … it just brings life, another year’s worth of feed.”

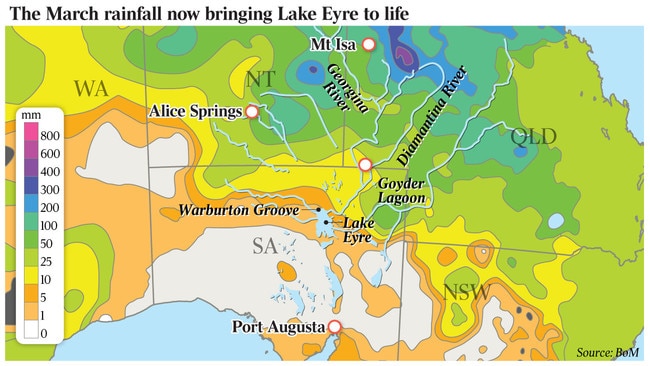

Wind back the clock two months, and the flood was monsoonal rain tumbling from a bruised sky on to the parched, black soil of the Barkly Tablelands south of Mount Isa and the far-flung catchments of the great inland rivers that drain to Lake Eyre through 1000km of the nation’s harshest landscape.

More than 95 per cent of it has been lost to evaporation and soakage, and to replenish countless dry waterholes and billabongs. The Georgina River is running strong, tipping water by the megalitre into Goyder Lagoon, north of the lake proper, a 100km-long marsh thick with bird life and fresh greenery.

There, the torrent mixes with what’s come down from the Diamantina River, which snakes through the channel country straddling the Queensland-South Australia border and the burning sands of the Tirari Desert.

What an experience it was for Rex Ellis, 76, to ride the head of the flood in a 4m launch after it funnelled into Warburton River on the last leg to Lake Eyre. At the sharp end, the water frothed and bubbled beneath his boat like shooting river rapids.

“You could have walked alongside of it if you liked,” he said. “We would stop for a bit and then get going again, chugging along behind the head until we ran out of water. It was pretty special.”

Creatures great and small are making the most of the ephemeral season of plenty. At the bottom of the food chain, the copepods, ostracods, conchostracans and all manner of seed shrimp have emerged from eggs that were laid down the last time the rivers flowed, two years ago.

“Add water and away they go,” said Professor Kingsford.

He said that in no other part of Australia was water so important as in the desert.

“The desert responds in a way that I never cease to be amazed about,” he said. “It all happens at an amazing rate. Those of us who are working in this business only get a quick vignette of what is going on … there is much we don’t know, except to say these are such critical events in the whole river system, and for the animals and plants that depend upon it, as well as the people, obviously.”

As well as carrying full-grown fish, the water also brings fish larvae, which thrive in the brimming waterholes and wetlands. The cloudless sky is full of birds: willie wagtails, white-backed swallow, waders such as the red-necked avocet and chestnut-breasted Australian shelduck. If there’s enough water, the majestic pelicans might stay on to breed on islands that will form in Lake Eyre.

Mobs of wild camels are coming in from the Simpson Desert, hundreds of kilometres to the north, to eat and drink their fill.

Mr Ellis’s camp was approached by dingoes that had never before laid eye on a human.

“They walked up to us like tame dogs,” he marvelled.

The lake has not completely filled since 1974 and the size of this flood is anyone’s guess.

Bush pilot Trevor Wright, who has been tracking the water’s progress this week through Warburton Groove in a kilometre-wide column, said it looked like a “medium-sized” inundation, probably the biggest since 2011 when the lake reached half-capacity.

He should know. From the headquarters of his aircraft charter business, Wrightsair, at nearby William Creek, population 12, Mr Wright has seen just about all there is to see of Lake Eyre over the past 30 years. Still, he’s surprised by how late this flood is.

“We’ve never had the water come in at this time of year,” he said. “It’s good, though. The country is the worst I’ve seen it.

“The roads are starting to break down with the dust and the rabbits are moving in on any vegetation they can find. All the trees are stressed. It’s great to see the water finally come down — it definitely lifts the spirits.”

Tourists are starting to arrive and the Lake Eyre Yacht Club is back in business, sailing Warburton River, which is running at 4m.

For now, the water coursing into the salt-encrusted lake is pink and earthy. By yesterday, the column had advanced more than 50km. As it pushes deeper, the suspended particles will fall away. By the time it reaches Belt Bay and spills across the dry lake bed, the water will sparkle.

Come spring, most of it will be gone and the cycle will reset, from boom to dust, as it has for time immemorial in the outback.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout