Millions at risk as China miracle crumbles

China’s economy — the world’s second-largest, Australia’s biggest trading partner — is in a bad state.

From top to bottom, the Chinese economy — the world’s second-largest, Australia’s biggest trading partner and for decades the source of almost metronomic growth — is in a bad state.

Up in the north, one of the country’s most senior entertainment executives, Huang Wei, 52, who ran the cinema operations at Bona Film Group — a huge private business that has been decimated by coronavirus restrictions — a fortnight ago jumped out of a Beijing building to his death.

And that was days before the 21 million residents of China’s capital were last week ordered to stay inside as a new coronavirus outbreak from the enormous Xinfadi wholesale food market — the biggest in Asia and, according to officials, the supplier of 70 per cent of Beijing’s vegetables — shuttered businesses throughout the city once again.

Things don’t look much better in the industrious south, as The Australian discovered on a tour through Guangdong and Fujian provinces, which have a combined population of more than 150 million and, until this year, had been two of the key engines of China’s extraordinary economic growth over the past 40 years.

From car dealers in Quanzhou to factory workers in Guangzhou to street sellers of fake tax receipts in Shenzhen, these are hard times.

Still, workers such as Mr Chen, a sixty-something fruit seller in Xiamen — a port city in Fujian that in the late 1980s had Chinese President Xi Jinping for a vice-mayor — say they are relieved to be able to earn any income at all.

“I can’t rely on my son. He’s a labourer; he can barely support himself,” Mr Chen says at his rudimentary street stall where he sells “shan zhu”, a fruit popular in China’s humid south.

With hardly any visitors coming to the city — normally a popular domestic tourist destination — Mr Chen said business was “not good”. But after being unable to work for months because of the coronavirus lockdowns, he is grateful for any income to supplement the just over 100 yuan ($20.50)-a- month aged subsidy he receives in the People’s Republic of China, which — while run by the Chinese Communist Party — is in many ways a much more capitalistic society than a mixed economy such as Australia’s.

Much of the healthcare system in China is user-pays, which is a huge concern for hundreds of millions of workers living off their savings as their incomes have shrunk.

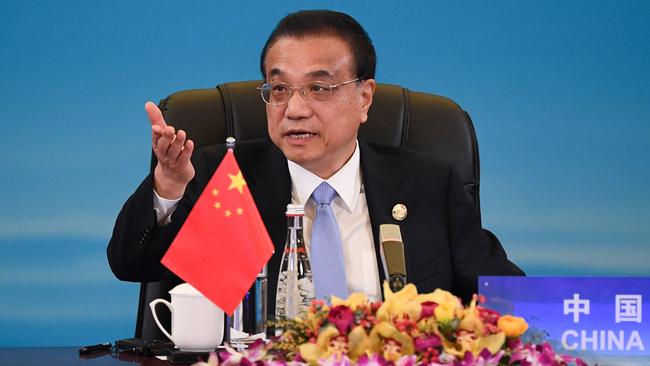

Chinese Premier Li Keqiang revealed last month that 600 million people in the emerging superpower — more than 40 per cent of its 1.4 billion people — live just above the poverty line.

“Their monthly income is barely 1000 yuan ($205), not even enough to rent a room in a medium-tier Chinese city,” Mr Li said, in comments that triggered a domestic debate about working-class life in contemporary China.

Shenzhen, the Blade Runner-like metropolis in Guangdong — which before the COVID-19 restrictions came into force was a 15-minute, high-speed train trip to Hong Kong — has for decades been one of the fastest-growing cities in China.

The city of about 20 million people is the home of the Chinese tech giant Tencent, which owns WeChat, a phone app that is ubiquitous in China. Tencent is worth more than $500bn and, along with $875bn e-commerce behemoth Alibaba Group, is a rare Chinese company to have gained value during 2020 as consumers have spent much of this year’s first six months online while stuck in their apartments.

Tencent and Alibaba’s growth — increasing the astronomical wealth of their founders, Pony Ma and Jack Ma, worth $73bn and $64bn respectively — has been at the expense of bricks-and-mortar stores, which employ far more people in places such as Shenzhen’s enormous electronics markets on Huaqiang North Road.

Li Xiaohua works on the third floor of one of them in a toyshop, selling remote-control sharks (promising “real lifelike movement”), electronic drum pads (which the store’s only customer other than The Australian is trying out) and a range of toy robots.

Ms Li says drones are the most popular toy in China right now, especially the Drone Pro, which is made in her home city of Shantou, dubbed the world capital of toys, in Guangdong’s east.

Yet even drones aren’t selling like they did before COVID-19. “People are more sensitive about the price,” says Ms Li as she demonstrates the Drone Pro.

Store owners say similar things across the market’s eight levels. Even the Shenzhen hipsters in the Bitmain store say COVID-19 has been terrible for business. “During the crisis, people want cash, not Bitcoin,” says a twenty-something agent, as his colleagues receive an order from Luckin Coffee, a US-listed Chinese chain in crisis after a scandal over fraudulent sales.

Underlining the point, no customers enter the Bitmain shopfront during the hour he talks to The Australian.

Over the road, a middle-aged lady seated next to an almost empty China Communications Bank branch is also struggling for custom. “Fapiao! Fapiao!” she calls out, touting fake invoices for people looking to minimise the income that they declare to China’s tax bureau. Even this illicit business is depressed. Less income means less tax to minimise.

A bit over an hour away on the fast train in Guangdong’s capital, Guangzhou, the economy looks to be in even worse shape. It is hard to be a world hub of international trade when international borders are almost entirely closed. And it is especially tough being a migrant worker in China when there are hardly any jobs available.

When The Australian visited the South China Market of Human Resources — the biggest in China’s south — its closure had been extended. Again.

“Because of the epidemic,” was all the thermometer gun-wielding security officer would say about the delay of what was supposed to be a June 3 physical reopening of a market that last year helped 2.18 million people find jobs, according to the market’s declared numbers.

The delayed opening of the mega market, which is backed by the Guangzhou government and the central government in Beijing, is more evidence of how the pandemic has unhappily surprised China’s leaders.

It is why Mr Li broke with modern orthodoxy and did not announce an economic growth target in his Work Report at the National People’s Congress, a gathering of the CCP’s governing elite. “This is because our country will face some factors that are difficult to predict,” Mr Li said.

He wasn’t wrong.

A scan of the paltry online jobs board of the South China Market of Human Resources — which finally reopened last Thursday — suggests a major cause in the delay of the market’s opening: there are few jobs to offer.

Most of the listings were for commission-based work: a phone sales job at an insurance company, a property agent at a real estate group, another sales job at a phone company.

It is also grim on the streets of downtown Guangzhou where factory bosses used to recruit migrant workers by holding boards listing jobs and conditions on offer.

“It was like going shopping. You could go there at any time of the day and easily find a job,” Zhang Yayun, 35, told the Shanghai online magazine Sixth Tone about life as a migrant worker in the city before the pandemic.

“Now we’re just trying to survive,” she says.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout