Men share women’s pain in nation’s jobs shock

Employment falls among men were higher than for women for several months this year, a reversal of earlier trends.

Young workers, casuals, sales employees and labourers have been among the hardest hit during the COVID-19 pandemic, with research revealing employment falls among men were higher than for women for several months this year, a reversal of earlier trends.

Analysis of the economic effects of COVID-19 prepared for the Fair Work Commission shows that after big falls in the number of hours worked by women compared with men in March and April, “the relative impact by gender evened up and reversed”.

The assessment by University of Melbourne economist Jeff Borland found the pandemic had a minimal employment impact on white-collar occupations. It also found employment levels among workers aged 55 and over had returned to pre-pandemic levels.

Jobs among community and personal service workers fell by almost 22 per cent in the first months of the pandemic, the highest single fall by occupation.

While large slumps in employment and hours worked occurred from March to May, the reopening of economic activity saw a rapid recovery from May to June, followed by a more steady improvement through to November.

Sydney production director Monique O’Callaghan was placed on the $1500 fortnightly payment in May after her hours dropped from up to 45 per week to just 20 due to the pandemic lockdown.

Ms O’Callaghan, who worked her way up from a freelance event co-ordinator to production director after 10 years at Sydney-based Event Planet, said the coronavirus restrictions limited her industry almost immediately.

“We had cancellations, postponements and negotiations almost instantly, which took up probably the first two months post restrictions coming into place,” the 32-year-old said.

“In our industry, a standard working week is 37½ hours but it can often be more … we could have been working up to 45 hours a week in our busiest periods. Dropping to about 20 a week was a big adjustment … I kind of felt I had to fill every single hour of those 20 hours to feel productive.”

Ms O’Callaghan said she would remain on JobKeeper until March and was keen to be part of the industry when it was rebuilt.

“Our company is an all-female team … we saw the impact of the (lockdown) on females,” she said.

“For the most part we were able to continue working by working from home and adapt a little more. (That could be) to do with the style of work we do being office-based, as opposed to someone who might be a labourer, who physically can’t work from home.

“I think we’re lucky in that sense that we were able to keep some form of normality.”

All states experienced large falls in final demand and employment numbers in the March and June quarters, but by the September quarter, final demand in Western Australia, South Australia and Queensland had almost returned to March levels. Monthly hours worked in those states in November were either higher than or back to within 1 per cent of their March levels.

By comparison, due to Victoria’s second coronavirus outbreak, demand in the state in September remained 9.5 per cent below March, and monthly hours worked were 13.8 per cent down, before improving by November to be 4.5 per cent below March.

Industries most adversely affected in proportionate terms have been accommodation and food services and arts and recreation services, with employment initially falling by 35 per cent and 28 per cent respectively. By contrast, jobs in other industries were 6 per cent lower in the first months of the crisis.

By mid-July, jobs in the two worst-affected industries were back to about 15 per cent below mid-March levels. While some further recovery in arts and recreation occurred by early October, the size of the job falls remained higher than other industries.

Professor Borland said that COVID-19 had had a relatively even impact on the employment of males and females. Job losses for women were larger than for men from March to April, when monthly hours worked fell by 12 per cent for women and by 7.7 per cent for men. He said the difference seemed to mainly reflect that women were more likely to move out of the labour force, or if they remained employed were more likely to have reduced hours of work, including a disproportionately large share of zero hours.

However, after the initial months, the relative impact by gender evened up and reversed. From May to November, monthly hours worked grew by 10.2 per cent for women and just 8.3 per cent for men. From March to November, the l fall in monthly hours worked was 1.6 per cent for women and 1.2 per cent for men.

Part-time hours fell 19.9 per cent between March and May but rebounded by 22.2 per cent between May and November. Full-time hours initially fell by 8.5 per cent, but grew between May and November by 6.7 per cent.

Professor Borland said the subsequent strength of the recovery in part-time employment was partly the reversal of the initial effects of the lockdown.

“With the reopening of economic activity, the same industries that were worst-affected have recovered most strongly, and with that part-time jobs in those industries have been restored,” he said.

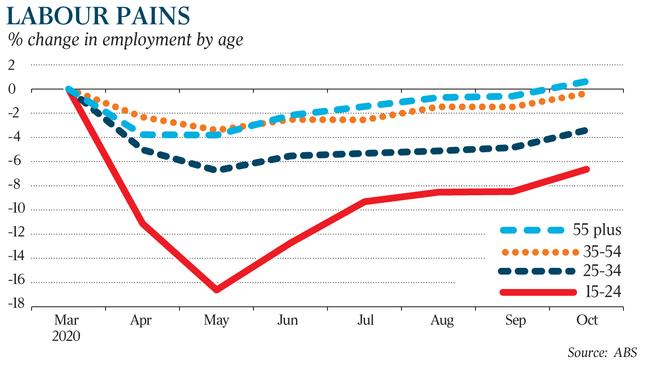

While the recovery has been stronger for younger than older workers, large differences in the size of the impact on employment between age groups remained by October. Employment for 15 to 24 years olds fell by more than 16 per cent by May and was still 6.6 per cent below March levels in October. Among 25 to 34 year olds, employment had slumped by more than 6 per cent in May and remained at more than 3 per cent above March levels in October.

Employment falls among older workers was less severe, falling among 35 to 54 year olds by about 3.5 per cent by May before returning close to pre-pandemic levels. For those aged 55 years and above, it was slightly higher in October than it was in March.

Weekly hours worked by casuals fell by an extraordinary 27.6 per cent from February to May before growing by 10.5 per cent in the four months to August.

The number of casuals employed initially slumped by 20.6 per cent before rebounding by 7.7 per cent.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout