Lost children of Australian aid worker live ‘minute by minute’ in hell of Gaza

Life was difficult enough for the late Jean Calder’s physically disabled adopted children in Gaza. And then war came, unleashing nightly fear and even more hardship.

Dalal Altaji says the grittiest Australian couldn’t stand a single, hellish night in Gaza. That’s why she and her adopted brother, Badr, live minute to minute, hour by hour, and try not to think about what the future will bring.

Dalal, 50, is speaking in Arabic and English from their refuge in the Palestine Red Crescent Society’s Al-Amal Hospital in Khan Younis, an area once known for its thriving market gardens and 14th century Mamluk ruins.

And as a bolthole for the leadership of Hamas.

Now, like the rest of Gaza, it is a moonscape of bombed buildings and grey concrete rubble.

The home they made with their adoptive mother from Queensland, the late aid worker and internationally renowned disability advocate Jean Calder, is gone. A plate of salad has become the height of luxury. Fresh bread? Peace of mind? All holdovers from a better time.

The challenges they used to face in dealing with an exacting lot in life – she was born blind and Badr, 38, has cerebral palsy – pale against surviving another 24 hours in Gaza.

But if the days are bad, night-time is worse. The fear and uncertainty somehow seem more overwhelming when darkness descends.

“I don’t think the average person could cope with an hour, not a night here,” Dalal tells The Weekend Australian when our phone call finally connects on the patchy network.

“You just don’t know if you will wake up tomorrow and it’s a feeling that’s very hard to explain. There’s been countless nights where I thought I wouldn’t wake up to see the next day.

“I’m in the hospital now and I’m not going to tell you I’m in a safe place, because there’s no safe place when you … are under fire. It’s really horrifying.”

The story of Dalal, Badr and the kind, caring Australian who took them in as children offers an insight into the struggle Gazans face, 14 months into the war Hamas started on October 7 last year when it sent hundreds of fighters swarming into southern Israel. More than 1200 Israelis were murdered in the rampage, women were raped, 251 people abducted and countless others injured or traumatised, unleashing carnage and turmoil across the Middle East.

In the latest domino to fall, Syrian despot Bashar al-Assad this week fled his palace in Damascus to complete the humiliation of Iran’s “axis of resistance” aligned against the Jewish state.

None of that matters to Dalal. She just wants the fighting in Khan Younis to end. “I’m sort of glad that I’m blind so I don’t see the destruction … but I can definitely sense it,” she says.

More than a mum

Calder’s death in November 2018, at the age of 85, devastated the daughter she thought of as her own flesh and blood. “She was more than a mum,” Dalal says sadly. “Losing … her was like losing everything, like losing my arms and my vision again.”

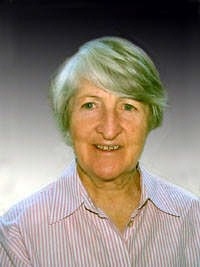

Born near the north Queensland sugar town of Mackay, Calder had spent 25 years teaching school in Australia before the plight of the Palestinians gripped her. After earning a PhD in physical education from Pennsylvania State University in the US, she made her way to Beirut in 1981 – at the height of the vicious Lebanese civil war – to work with physically and intellectually handicapped children.

She met five-year-old Dalal in the teeming Burj Al-Barajneh refugee camp: the little girl had been abandoned or orphaned as a baby and didn’t even know her family name; Altaji had been selected for her.

Calder stepped in, adopting her along with Badr and a second boy, Hamoudi, also affected by cerebral palsy. (He died in 2013.)

When the Israelis invaded Lebanon in 1982 to expel Yasser Arafat’s Palestinian Liberation Organisation, she packed up her little family and moved to Cairo, where Dalal finished high school. The Oslo peace accords between Israel and the PLO allowed them to go to Gaza in 1995.

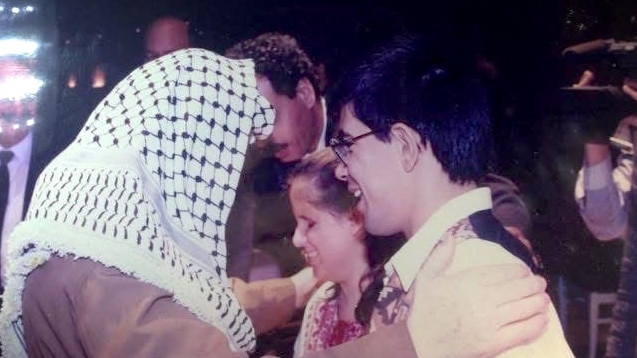

Calder, by now a world authority in her field, set up a child rehabilitation there under Arafat’s younger brother, Fathi, boss of the Palestine Red Crescent Society. The chatter that their relationship was more than professional is wrong, Dalal insists.

Still, “Dr Fathi” played a big role in her life, as she continued to study. “Yes … he was like a brother and a father … he supported me a lot, supported all of us. I knew his sister and children very well,” she remembers.

Dalal became the first blind woman to attend Cairo’s elite Al-Azhar University, the oldest in Egypt and a seat of Islamic learning. A Ford Foundation scholarship in 2003 took her to the University of Aleppo in northern Syria to study social anthropology, after which she returned to Gaza to lecture at a local university. She shared an apartment with her adoptive mother until Calder’s death, while Badr lived downstairs with his wife. They relied on each other for the support that wasn’t available to disabled people in Gaza. Life wasn’t easy, but they got by.

All the while, the drums of war continued to beat.

In 2005, Israel unilaterally pulled out of Gaza – which it had occupied since the Six Day War in 1967 – and sealed off the enclave with the security fence that would be disastrously breached by Hamas in the October 7 breakout. The periodic eruptions of fighting between the Islamists and Israelis were compounded by a blockade that choked the supply of food, services, medicines and other necessities to the 2.3m Palestinians sealed in Gaza, making their lives grimmer and grimmer.

“I experienced the war in Lebanon, which was, of course, not easy,” Dalal says. “I experienced the 2009 war and the 2014 war in Gaza. Although we stayed in our house, things were much better than now … the war in 2014, which lasted 51 days, was also very frightening, but not as bad as now.”

Surreal morning

Dalal vividly remembers the surreal morning after Hamas’s surprise attack. It was a Sunday, the start of the working week. She had been jolted awake at 6am by the crump of Israeli rocket fire.

Dalal recalls: “Nobody knew what was happening – and then we saw the news. To be quite honest, people were a bit happy, thinking that, you know, all would be OK. But I always had the feeling that this would bring about something very serious.”

Four days later, the house behind their building was bombed. The blast was so powerful it wrecked the home she shared with Badr and his wife.

“I was sitting on my bed … checking the internet and I thought I was going to get up and make myself a cup of tea,” she says. “Just as I thought to do that, we heard a very loud bang, and then all the glass broke. I think it was a blessing that we survived.”

The onslaught intensified. Israeli soldiers arrived soon enough, engaging the Hamas men in bloody dayslong gunbattles, supported by tanks and artillery. Sunset brought no relief: the night terrors took wing on air strikes.

South-lying Khan Younis was as good as it got in Gaza, about 40 minutes from the Egyptian border, which was why so many of the big shots in Hamas had called it home. Inevitably, this meant a lot of the terrorist group’s infrastructure was positioned there as well, making the area a go-to target for the Israel Defence Forces.

The collateral toll ran to countless civilian deaths.

The family wanted to stay put, despite the damage to their home. But this proved impossible under the Israeli bombardment. Reluctantly, they joined the throng of refugees headed to Rafah, straddling the closed border. They lived in a tent for four long, arduous months. “For people with a disability … it was very difficult,” Dalal says.

She is grateful for the roof over their heads at Al-Amal hospital, which temporarily ceased operations in March. They get some help from the Palestine Red Crescent Society, but it’s not enough. There’s never enough help in Gaza. Dalal continues to work as a lecturer at the University College of Ability Development, next door to the reopened hospital. The staff try to teach online – highly problematic given the internet is more often down than up. Badr works in the PRCS rehabilitation centre, doing what he can.

“The worst part for me is hearing about the horrors my people go through,” she says. “Hearing the bombs constantly dropped and knowing that innocent people are being killed. We are really oppressed, but I try to cope. I try to tell myself, ‘Don’t be worried’.”

She knows she’s lucky to have a salary coming in. But getting money out of her account isn’t easy. Most banks have shut down.

If you can access cash – and hard currency is all the shopkeepers and merchants take – the prices in the market are prohibitive. “To have a plate of salad at the moment is a luxury because tomatoes and everything else is very expensive,” Dalal says. “To … get bread is very difficult as well.”

She is reluctant to venture a view of Hamas – “I’m scared … I don’t want to speak about politics” – but accepts that Gaza went “backwards” during the 17 years in which the Islamists wielded iron-fisted power. “There will be no peace with them,” she says.

Living in the now

As for the Israelis, Dalal has little time for them, either. “Tell me one good thing they ever did for us,” she demands. “They … broke our hearts, our will to live. People lost their entire families, homes, because of them. They have been doing this for decades … I really feel that we have been living an injustice. I lost my house and my house means my memory, and what they’re doing is beyond comment.”

Dalal has tried to reach out to Calder’s family in Australia in the hope they can do something, anything, to help get them out. Would she and Badr come to this distant land if they could? “Of course,” she says.

But that’s for another day. She has to live in the here and now, and in Gaza that’s a minute by minute, hour by hour proposition. What’s the point of dreaming about a tomorrow that might never come? “I don’t know what else to say,” Dalal says, thanking us for calling. “May God bless everyone and keep us safe.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout