Lobster smugglers get around China’s Aussie trade bans

Hundreds of millions of dollars worth of lobsters have been smuggled into China over the past two years through uninhabited islands and narrow stretches of water.

The great Australian lobster racket has never been more lucrative: hundreds of millions of dollars worth of the bright red contraband has been smuggled into China in the past two years and business is booming ahead of the Lunar New Year holiday.

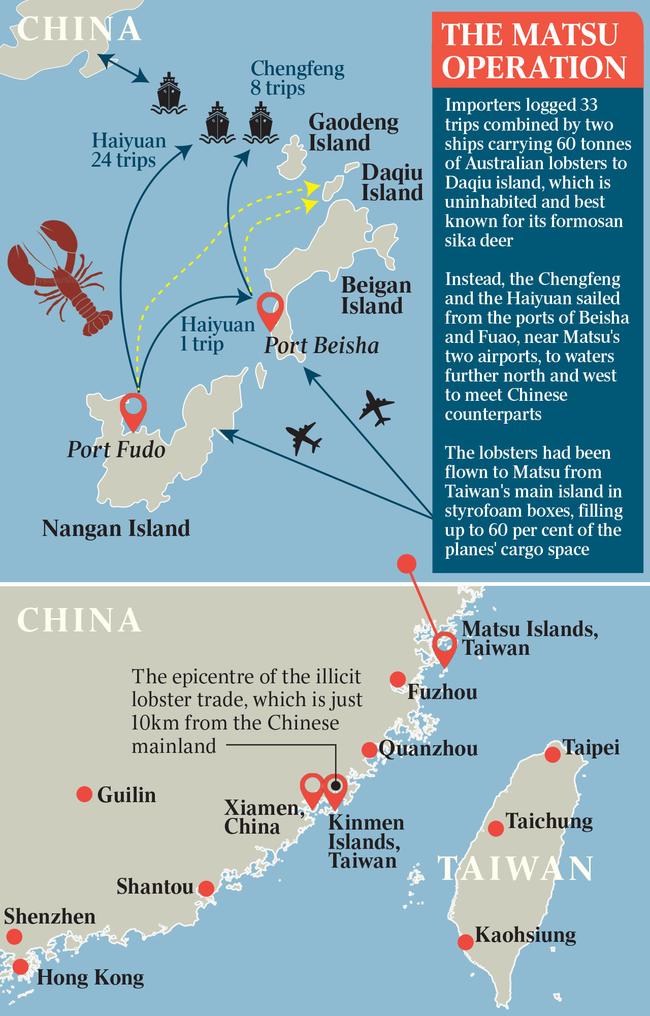

The new epicentre of the illicit trade is the narrow stretch of water between Kinmen and Matsu, Taiwan’s westernmost islands, and the Chinese province of Fujian, as close as 10 km away.

“Taiwan’s the door to China at the moment,” says one Australian lobster farmer.

Groups of young men, many linked to local gangs, have become a common sight at Kinmen’s airport as they wait for planes that arrive from Taipei packed with China’s most prized banquet food: Australian lobster, called “Aolong”. Matsu’s air cargo channels have been jammed with styrofoam boxes packed with the live delicacy.

Crime gangs in Hong Kong and Taiwan have been the biggest winners from Beijing’s tacit instructions to China’s customs officers in late 2020 to block Australian lobster, part of a sweeping campaign of trade coercion launched after the Morrison government called for an inquiry into the origins of Covid.

Australian lobster farmers – whose profits have since been pilfered by an assortment of criminals, opportunists and dodgy officials – and Chinese customers have been the biggest losers.

There is chatter in Australia, China and Taiwan that Beijing may soon lift its ban on the trade, which was worth more than $750m in 2019. It would be a low cost way for Beijing to send a “positive signal” to the Albanese government as it courts support for China’s application to join the giant CPTPP trade pact. It would also clamp down on a thriving source of local corruption.

“We’re being told the front door’s going to open soon,” says a well-connected member of the Australian lobster industry, citing people in China claiming to have government connections.

“But China’s China. You can’t believe everything you hear,” he tells The Australian.

All the while, Australian lobsters keep finding their way into China. Right now, they are being sold at record prices.

Down in Guangdong, in China’s south, a seafood seller assures customers his bright red catch is “Australian lobster, not Mexican”. He offers home delivery within 48 hours.

Up in the north in Beijing, The Australian this week found China’s most coveted seafood on sale at a market vendor for 1260 yuan per kg ($270 a kg).

That’s more than three times the $70-90 per kg Australian lobster exporters are currently selling for – a profit margin that has proved tempting for many enterprising smugglers.

The lobster trail

Formosan sika deer are not known to be fans of lobster, not even the premium stuff from Australia.

That was why the 33 combined trips by lobster importers to Daqiu, an island uninhabited by people and best known for its hundreds of deer, was highly suspicious. The two ships had declared carrying a total of 60 tonnes of live Australian lobsters to the outlying Taiwanese island between September and November last year.

“It would be highly unusual for the deer to consume 60,000kg of Australian lobster,” Wen Lii, director of the Democratic Progressive Party’s office in Matsu Islands, tells The Australian.

Mr Lii has helped establish a paperwork trail that outlines in unprecedented detail how Australian lobster continues to get into China.

Working with Hung Shen-han, a legislator in Taiwan’s parliament and fellow member of President Tsai Ing-wen’s DPP, he got the Matsu Coast Guard to hand over the cargo records of the two ships.

Further requests to Taiwan’s Coast Guard for navigational tracing of the ships – named the Chengfeng and the Haiyuan – showed they had lied about their final destination.

They had sailed from ports near Matsu’s two tiny airports, loading their ships in broad daylight. Instead of sailing to Daqiu, a place tourists call “deer watching paradise”, each time they travelled to waters further to its north to meet with Chinese counterparts.

“Only people with good political connections could do it,” says Mr Lii of the shady “ship to ship” transfers.

The operation quickly became the talk of the Matsu archipelago, which has a population of around 10,000 people.

Australian lobster had never been available for sale anywhere on the group of islands. Now Matsu’s two main ports, Beisha and Fuao, were crawling with the pricy crustaceans.

Even bigger numbers have been trafficked through Kinmen, whose population of 120,000, making the trade relatively less conspicuous than in Matsu where it reached outlandish proportions.

For much of the second half of 2022, up to 60 per cent of the cargo space of the small propeller planes that fly to Matsu from Taiwan’s main island were filled with styrofoam boxes of live Australian lobsters.

It’s how Mr Lii was first tipped off about the syndicate.

“Somebody notified our office to say that the plane cargo space was clogged up with Australian lobsters. It was causing a hassle for many local businesses.”

A gift from the sky

Beijing has never made its Australian lobster black-listing official.

The industry learned about the new policy when China’s customs officers left 21 tonnes of Australian lobsters to die on the tarmac of Shanghai’s international airport in November 2020. Since then, no Australian lobster shipment has been officially cleared by Chinese customs.

But demand for the most sought-after shellfish in China never went away. And, helpfully for smugglers, Chinese officials have been much more permissive about sales of Australian lobster within the country.

Despite threats by Beijing’s mouthpieces that upset Chinese would no longer buy Australian products, “Aolong” has remained a fixture at the weddings and celebrations for many urban elites.

“The reputation of Australian lobsters is undiminished,” says a food importer in Shanghai.

In 2021, Hong Kong was the main hub for lobster smuggling operations into China. Imports of live Australian lobsters surged 14 times from the pre-ban era to more than 1300 tonnes.

That racket mostly dried up at the end of 2021 as Hong Kong officials clamped down on the trade after it was extensively reported in the city’s media.

One zealous Hong Kong official even made a rare public admission of China’s ban.

“These activities undermine our country‘s trade restrictions against Australia,” the city’s customs commissioner Louise Ho declared in October 2021, confirming a trade policy that had never been made official.

“Stopping lobster smuggling is a very important part of protecting national security,” she added.

The trade then migrated to Taiwan. There are now about 100 times as many live Australian lobsters coming into Taiwan than before Beijing’s blacklisting.

In 2022, more than 1400 tonnes of lobster was imported. In 2019, it was just 14 tonnes.

One Kinmen resident involved in the trade recently told the Taiwanese investigative media outlet the Reporter that this has been a special time for local smugglers.

“This is a gift that fell from the sky,” said the resident.

But there are signs the boom times for smugglers across the Taiwan Strait may be endangered.

This month’s reopening of the land border between Hong Kong and mainland China has allowed logistical opportunities denied to the city’s smugglers during the pandemic years. Lobsters can again be hidden among other goods in trucks or hauled by human couriers into Guangdong.

An even bigger risk for Taiwan’s lobster racketeers is the Albanese government. No one will be more closely watching the trip to China by Trade Minister Don Farrell, as the syndicates in the Taiwan Strait. The Minister’s trip may be as early as February.

Back in Australia, some worry that if Beijing ends the ban the industry will again be far too dependent on a single, highly political market. Before 2020, more than 90 per cent of Australia’s catch went to China, where the profit margins were unmatched.

“I’ve got mixed feelings about it,” says the owner of an Australian lobster business. “I want us to keep our diversity in case this happens again.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout