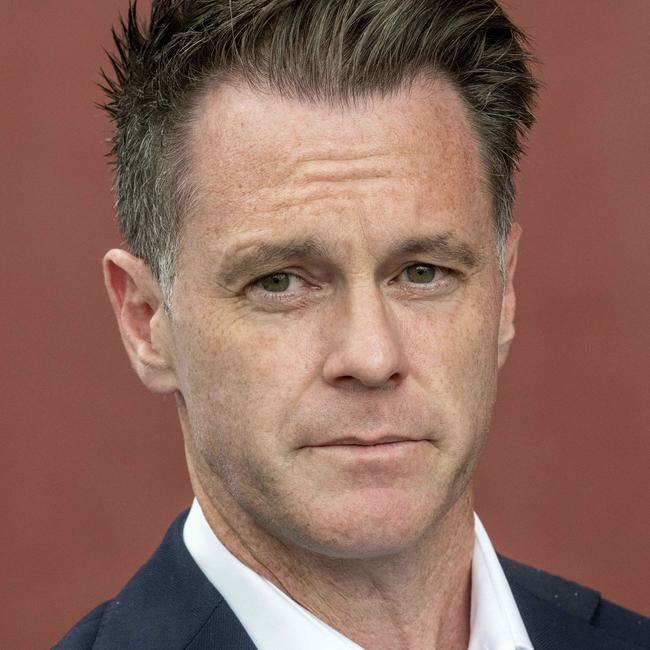

Liberal Party splits left Dominic Perrottet with mountain to climb in NSW election

What hope did Dominic Perrottet have in the NSW election when the Liberals were focused on themselves?

It was already difficult for Dominic Perrottet to persuade voters at last month’s NSW election that his government deserved another go.

The NSW Coalition was showing its age after 12 years in power. Perrottet’s attempt to project vitality and renewal did not tally with a conspicuously high number of government MPs, including senior ministers, deciding it was time to retire.

The NSW Premier’s problem was compounded by another staring at him in the face: his party was in a mess.

What hope did Perrottet have when the NSW Liberals were focused on themselves, seemingly more intent on fighting each other than winning an election?

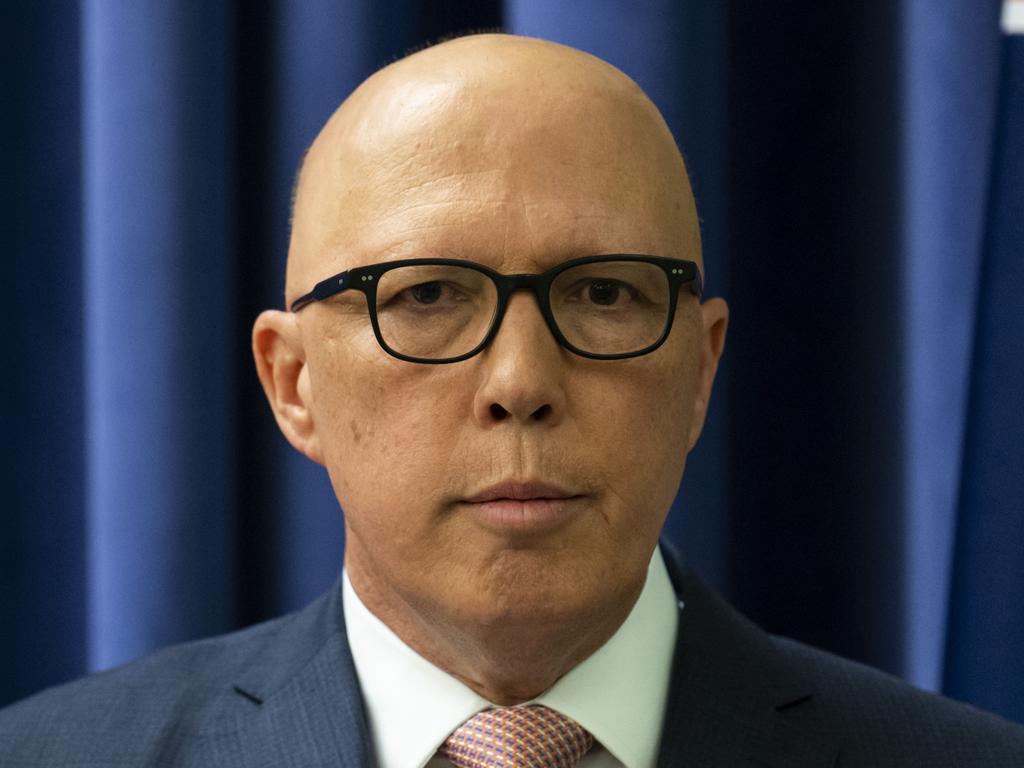

Scott Morrison faced a similar obstacle at the federal election less than a year earlier. Factional warfare and personal squabbles consumed the NSW branch of the Liberal Party and figured in Morrison’s poor results across the state, beyond his own failings as prime minister.

The NSW Liberals repeated a big mistake ahead of last month’s state election by not preselecting enough good candidates and giving them time to campaign.

Continuing internal spats, often fought out in public, reinforced the image of a dysfunctional party that could not be taken seriously. Dysfunction ran from the NSW Liberals’ state executive at the top to local branches at the bottom.

There were signs of Perrottet’s mounting despair as Morrison headed for his election debacle. He told ABC radio: “I can tell you, when it comes to the next state election, I do not want to be in a position where I do not have people representing the Liberal Party in seats.”

He was. Liberal insiders say the 27-member state executive, which runs the party and controls the timing of candidate preselections, must take responsibility.

One dismayed senior Liberal told The Australian: “There is no doubt the state executive has got to see itself a lot more as the servant of the party rather than treating the party membership as its minions. The state executive should have a particular focus, which is, how do we win government? If that was their focus, rather than allowing powerbrokers to build their kingdoms, we’d be doing a lot better.”

Faction friction

Under the NSW Liberals’ constitution, the party’s soon-to-depart state director, Chris Stone, sits on the executive but has no vote. The 26 others vote on all matters. None is permitted to be a serving MP, except for the two spots reserved for the federal and state parliamentary leaders, or their proxies.

A shortage of direct parliamentary input (the party leaders rarely, if ever, attend) risks a disconnect with the state executive. Whatever its flaws, the NSW Labor Party’s equivalent administrative committee has five serving MPs and a smattering of experienced former MPs.

NSW Labor got its act together a while ago by putting aside a lot of old factional differences. Without that step, the party would be still mired in infighting. It would never have united behind Anthony Albanese, historically from the party’s minority left. Without such broad agreement, it would have been harder, too, for the new NSW Premier, Chris Minns, when differences arose between his faction, the Labor Right, and the party’s left. The final key to Labor’s stability at election time is agreement years ago on quotas for women candidates. “The Labor Party looked more like the community at the state election,” one Labor insider said.

NSW Liberals’ spats over candidate preselections are not new. But the party’s state executive functioned reasonably well three to four years ago when the dominant right and left factions worked together in an unofficial compact, even if a significant motivation was to shut out the minority Centre Right group.

While not personally present on the executive, Perrottet led the right and fellow Liberal minister Matt Kean led the left. As recently as October 2021, Kean delivered the parliamentary numbers for Perrottet to succeed Gladys Berejiklian as premier. For a while the NSW Liberals’ loose left-right pact neutralised the much smaller Centre Right, controlled by then federal minister Alex Hawke.

But the peace did not last. Hawke’s faction became a key force in the middle. Especially when the Right splintered into a subgroup loyal to dumped senator Concetta Fierravanti-Wells, and some Liberal Left members shifted their allegiances.

When he served as Morrison’s representative on the NSW party executive before last year’s federal election defeat, Hawke copped significant blame for delays in selecting candidates by allegedly missing meetings called to vet candidates.

Hawke was busy as a Morrison minister, but his critics privately accused him of deliberately stalling in a quest to impose candidates he and Morrison wanted. When it was too late for local branch preselection ballots, the party hierarchy picked candidates. One state executive member loyal to Fierravanti-Wells and her splinter right group, Matthew Camenzuli, took legal action against Morrison and the party to try to stop outside intervention. The matter was ultimately dismissed in court and Camenzuli expelled from the party, but the rancour carried on to the March state election.

Nazi ‘hit’

As March approached, Perrottet was hamstrung. The state executive was distracted by infighting and would not open remaining local branch ballots to select candidates. Worried that the NSW Liberals were lagging in female candidate representation, Perrottet intervened by demanding more women on the party’s NSW upper house election ticket.

He did so at a cost to himself when brawling spilt into the open, including among some in his own right faction. The embarrassing revelation, in mid-January, that Perrottet wore a Nazi costume to his 21st birthday, almost 20 years earlier, came not from traditional factional opponents on the left but disgruntled sources close to the then NSW premier’s right group in Sydney’s west.

These were disgruntled supporters of displaced male NSW upper house MPs ousted to make way for more women.

More damaging information about another Liberal MP, Peter Poulos, and others, was spread by a Twitter feed called @LibGoss set up to spread gossip “from the inner workings of the Liberals”. The bad blood was picked up by some mainstream media.

One senior Liberal, a former minister and factional player sympathetic to Perrottet, maintains the party’s main problem, as internal polling showed, was its age. He also downplays the impact of questionable state party governance and candidate selection delays. But he conceded: “We needed a lot more things to go right, and our message was clouded by internal fighting and scandals.

“What had an impact was a lot of people in the organisational wing who actually didn’t want us to win. They were actively trying to sabotage the government and blow up the party.

“These were the people who did the Nazi hit on Dom. That element decided they would tear him down. Attacks on Dom did not come from the party moderates, the Hawke faction, or his part of the right faction. They came from some who believed it was better to lose than to have Dom as premier. The problem was, to an extent, frustrating the preselection process. But it was basically them waging guerrilla warfare on our MPs.”

A former minister from Perrottet’s right faction, speaking on condition of anonymity to be candid, says counter-productive behaviour was not limited to the state executive, or to local spats. “We have created a party that thrives on talking about itself,” he said. “I can never understand this, but I was astonished while I was a minister by the fact that there was so much indiscipline by ministers who craved media exposure rather than remaining in government.

“On the left, right and centre-right there were certainly people (ministers) who would walk out of cabinet and pick up the phone to a journalist. If there was a dispute in the party, they would play out the dispute through the media, not within the confines of the party.”

Leadership vacuum

Two Liberals drawn into a public war of words – despite sitting in the same cabinet room – were former transport minister and “spear thrower” David Elliott, from the Centre Right, and former treasurer Kean, from the left. Elliott accused Kean of “treachery” against Morrison during last year’s federal election. He later accused Kean of “distrust” for dragging out union industrial action that disrupted the rail network.

While Kean did not engage publicly, he did issue a public rebuff a month before the election when Elliott, after losing his seat in a boundary redraw, argued he should score the seat of ousted upper house MP Poulos. “What I’d like to see is a female fill that vacancy,” Kean said.

Another political headache for Perrottet was the seemingly endless saga over how former Nationals leader and deputy premier John Barilaro was appointed to a prize trade job in New York on a $500,000 salary.

Barilaro denies any wrongdoing and did not take up the position, but the fallout killed positive news from a big-spending election budget, trade minister Stuart Ayres was forced to resign, and questions lingered about Perrottet’s own role in the grubby affair.

The NSW Liberals still do not have a parliamentary leader following Perrottet’s decision to step aside, announced three weeks ago on election night.

The likely successor is the Liberal left’s Mark Speakman, formerly attorney-general, despite some speculation he might shift to federal politics in Morrison’s seat. Speakman could be a stopgap leader or face a long wait. It could take until 2031 to reclaim government, if Labor’s numbers hold for two four-year terms.

NSW Liberal insiders are more optimistic about winning back state government compared with the hard road for the federal party. It is weighed down, they say, by the complexity of the Voice referendum and policy decisions on climate change, energy policy and relations with China.

Senior NSW Liberals claim the party can be competitive at the next state election by clawing back five seats from Labor, and then negotiating with independents to form a 47-seat majority.

Wishful thinking? Maybe. At the very least, party leaders accept the NSW Liberals must find a common purpose to become a functioning force again.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout